The advent of sharing platforms and greater access to online media the world over means that cinefiles are paying much closer attention to Middle Eastern cinema than ever before. While Dariush Mehrjui’s 1969 masterpiece The Cow is often labelled as single-handedly pioneering the Iranian New Wave, nothing can compare to the worldwide acclaim that accompanied Asghar Farhadi’s Oscar-winning drama A Separation.

Just as the rest of the planet is discovering Persian film, Iranian filmmakers are also setting their sights further afield. With work set in Italy and Japan already under his belt, Abbas Kiarostami recently voiced a desire to shoot a movie in Cuba, so enthralled is he with the culture. With borders becoming increasingly blurred, it will not be long before the styles of Iranian and other cinemas of the world begin to bleed into one another.

As filmmakers find ways to skirt around the censors, their own styles are emerging thick and fast. Some shoot under the cover of darkness, others find ways to work with actors banned from performing, while others break films into segments to avoid strict licensing laws. Even when banned from making films completely, directors such as Jafar Panahi find ways to practice their art. Contemporary Iranian film is truly a tour de force.

Let’s take a look at some highlights from the 21st century.

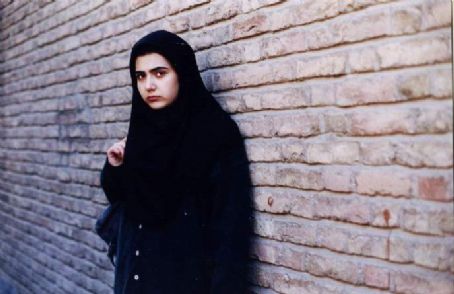

1. Under the Skin of the City (Rakhshan Bani-Etemad, 2001)

A quietly political drama, this moving film focuses on a family’s endeavours to escape the circumstances of its own class restrictions. Winner of the Karlovy Vary and Moscow International Film Festivals, Under the Skin of the City takes a compassionate look at the way families are forced to conduct their lives under dire straits.

One Tehran family serves as a symbol of Iran’s working class, and we follow them in their efforts to stay afloat financially and emotionally. Middle-aged matriarch Touba is forced to work in a textile factory due to her husband’s invalid status, while her eldest son Abbas becomes the main breadwinner through his work at a clothing wholesaler.

Just as Touba suppresses her own exhaustion in an attempt to put on a positive front, Abbas longs to move to Tokyo to earn enough to pursue a relationship with a coworker. The rest of the family also have their own crosses to bear; Touba’s younger son Ali is often on the wrong side of the law due to his participation in student demonstrations, while daughter Hamideh is continually on the run from her physically abusive husband.

Bani-Etemad’s background in documentary film is most evident in her decision not to gloss over her depiction of the streets of Tehran – we are shown the shabby areas as well as the more upscale shopping districts. More importantly, however, is the dignity she brings out in her protagonists. Each caught in their private traps, their various plights are handled with sensitivity and a sense of determination, even if we ultimately feel that Touba and her children are doomed.

This film offers viewers a realistic glimpse into the lives of the working class, and provides a social commentary on how people struggle to maintain a sense of normality when the odds are against them.

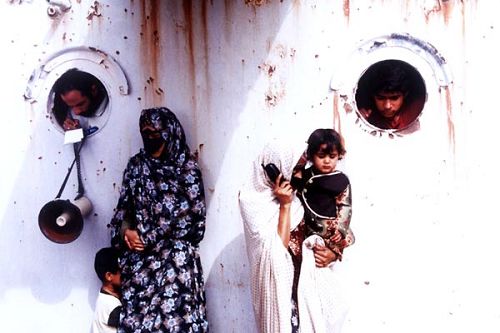

2. Iron Island (Mohammad Rasoulof, 2005)

An abandoned oil tanker becomes the principal location in this unusual film, and serves as a home for several destitute southerners. The commune-like existence they all share is run by “Captain” Nemat, who, no matter how benevolent a leader he is, must be obeyed by the residents on board. Young newcomer Ahmed realizes that there are rules on the ‘iron island’ when his pursuit of a pretty girl must be conducted under the cover of darkness. The strictly religious community also adds a layer of tension to life aboard.

The tanker’s self-sufficiency is evident in its numerous quarters, shops, schools, and even bakeries. However, despite its strengths, the vessel is slowly sinking as Nemat sells its parts one by one for profit. When the tanker’s owner announces his plans to scrap the ship completely, Nemat’s voice of concern is just as much about his own financial state as it is about the residents’ welfare.

While the ship can be viewed as metaphor for Iran’s politics, this would be far too dismissive of the tenacity of its inhabitants, whose shared home brings them together to form a loyal, comradely community. Despite Nemat’s monetary interests, it is apparent that he is emotionally invested in the lives of the people. The film is therefore not a simple black and white portrayal of capitalists versus communists; nor does it make any other formulaic contrasts.

Ultimately, Rasoulof’s film focuses on trust, and where it should be placed. Watching the citizens of the iron island go about their daily lives is a joy, and provides a heart-warming view of communal life.

3. The Willow Tree (Majid Majidi, 2005)

What if a man blind since birth was suddenly given the gift of sight? This is the central premise of this beautiful, gripping drama from Majidi, best known for Children of Heaven, and more recently, Muhammad: Messenger of God.

Youssef has been visually impaired for over thirty eight years, but this has not stopped him from carving out an idyllic existence for himself; a successful literature lecturer at a university, he shares a beautiful home with a loving wife and daughter. However, when a bout of illness sends Youssef to France for treatment, he discovers that there might just be a chance to restore his vision.

Majidi’s astonishing ability to capture intense emotion is evident in such scenes as when Youssef catches a glimpse of the world for the first time in decades – an ant trundling across a window pane elicits child-like glee, while the sound of birdsong is used to poignantly capture the beauty Youssef experiences in his unseeing life.

As Youssef familiarizes himself with the visible world, he becomes increasingly distant from his previous life, to the point of becoming infatuated with another woman. The film is very much a metaphor for ‘seeing’ what we have to be grateful for; while Youssef becomes enamoured with materialistic preoccupations to the point of obsession and selfishness, he loses focus on the things that made his life so blissful before.

From time to time, a film enables its audience to re-examine ideals and view its surroundings in new ways; in this film, an answered prayer for vision becomes a curse on a man’s personal life. Majidi shows us how to find beauty while confined to pitch black, as well as appreciate what we have, despite its shortcomings.

4. Santouri (Dariush Mehrjui, 2007)

Most likely due to its subject matter, this film has never been theatrically released in Iran. With themes of drug addiction, divorce, and homelessness, Mehrjui does not shy away from taboo topics, and it is no coincidence that “playing the Santour” is a colloquial Persian term for injecting heroin.

The narrative is told partially through flashback, and we learn that the once promising santour player Ali is now a washed up addict, performing at weddings for drugs rather than money, with only memories of his former life to sustain him. Whether or not he can find redemption remains a question mark for a large portion of the film.

At its heart, the film’s story is one of a downfall – of Ali’s career, his spiralling heroin addiction, and his failed marriage. We learn of how he meets and loses his wife Hanieh, and how a brutal act of violence can become a heavily disguised form of salvation.

Handheld shots and jump cuts lend a jerky, erratic realism to the film’s events, and serve to mirror Ali’s own shaky grasp of control in his own life. Ali, played with bitter conviction by actor-musician Bahram Radan, spits venom at contemporary Iran, but it is unclear whether the film mirrors his criticism. In Santouri, people suffer, but whether it is due to their own flawed personalities or the society that surrounds them is debatable.

5. About Elly (Asghar Farhadi, 2009)

Winner of the Silver Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival, Farhadi’s prelude to A Separation demonstrates his masterful ability to tell compelling stories of contemporary middle class Iran.

When a group of young friends and their young children take a trip to the Caspian sea, they take their daughter’s school teacher Elly along with them (Taraneh Alidoosti) in the hopes of setting her up with Ahmad, a recent divorcee over from Germany. The pair laugh along with the group’s jokes at their expense, and it seems that a genuine attraction develops between them. However, it is not immediately clear what Elly’s feelings are for Ahmad, or if she is even looking for anyone at all.

The tone of the film shifts considerably when a terrifying incident takes place on the waterfront, throwing the group’s gentle dynamic into panic and disorder. What captures our attention is not just the accident itself, but how quickly the young friends’ easy camaraderie is replaced by suspicion, rage, and accusation.

The film’s golden hues of the first half soon give way to subdued shades of oceanic blue, a visible interpretation of the characters’ sudden despair. The camera also serves to mirror the emotions of the characters, with languid, lazy sweeps depicting idyllic waterside play giving way to frenetic, darting zooms as panic descends on the group.

From the film’s jubilant, carefree beginning to the more somber chapters, interaction between the characters remains fresh and convincing; characters laugh and joke, mischievously pull open toilet doors on one another, and genuinely seem to enjoy spending time together. The performances seem almost improvised, such are their authenticity.

Farhadi’s talent lies in his ability to bring out natural, easy communication with his cast. It is noteworthy that Shahab Hosseini, who plays the gregarious Ahmad, went on to feature in Farhadi’s Academy Award winner A Separation.