“[…]But it all went down the drain with Freud and Darwin. We were and still are lost people.”

– Ray Bradbury, The Martian Chronicles.

Humans regularly pass through life without questioning the origins of small actions that compose us, that have been in us and ignored for a long time. Humans usually take for granted what inhabits us beneath our obvious physical biology, not because we are careless, or “unhumanised” (which seems as a grammar catastrophe), but because it is written all over ourselves.

As humans, in order to survive, we need to classify things, assign levels of importance to what surrounds us. After all those years of evolution, wanting and waiting to be “civilized”, we’ve kept a prevalent archaic heritage which guided us since the very beginning: the need of/for feeling in control.

1. A Clockwork Orange (1971, Stanley Kubrick) & 2. Black Swan (2006, Darren Aronofsky)

Behavioral studies have been conducted on a variety of subjects and species. From human-animal behavior to Ethology, the hypotheses of what, when, and how our conduct begins to forge are somehow familiar to us; thus, we constantly search empiric explanations, and often find ourselves in the same corners with the same questions clamoring for different answers.

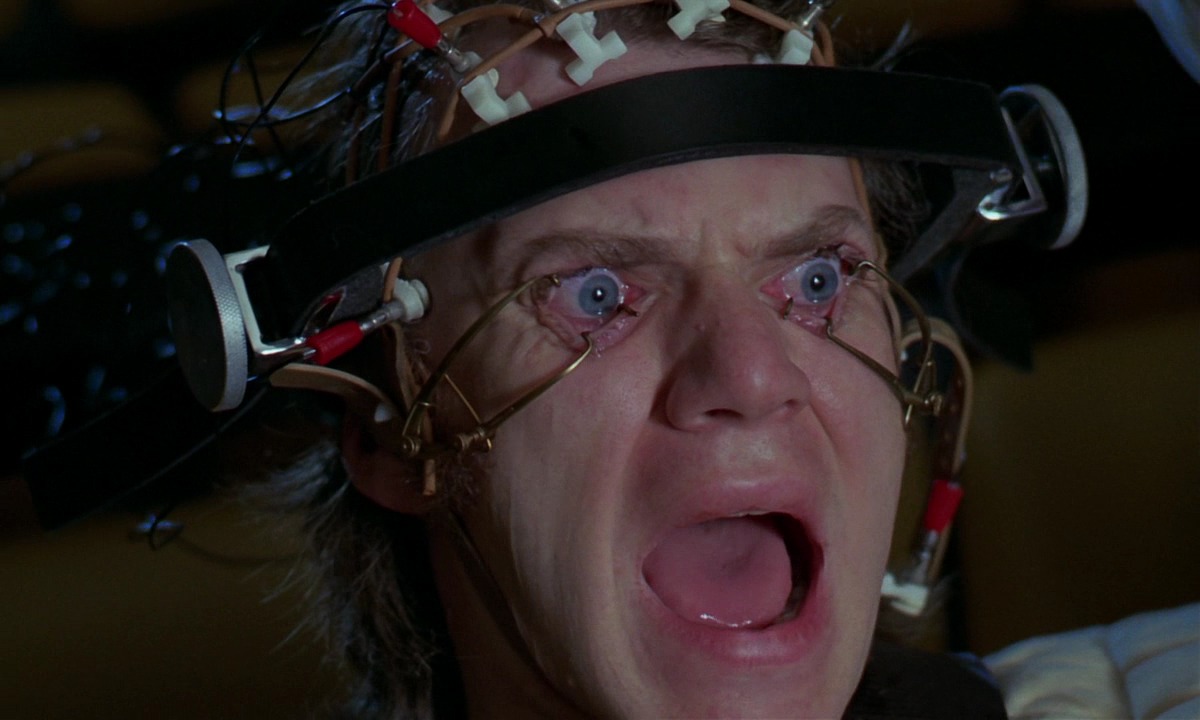

A Clockwork Orange may be the clearest example in movies of human conduct and behavior; of what happens when one is trained and indoctrinated from the inside out against or in favor of our will. The film shows what we are capable of when that sense of control is at our service, or taken away from us. The protagonist –and antagonist– Alex DeLarge is a textbook example.

With a well-known tendency for the macabre (on his reading selections), Stanley Kubrick ultimately is associated with gruesome fears. On the other hand, Darren Aronofsky shows in his works what fear and desire can cause on an individual.

Both Kubrick’s and Aronofsky’s films revolve around heroes –or antiheroes– which most of the time have little-to-no mental stability, giving each of their films a tension that is palpable from the beginning. By adding in a misleading understanding of what is going on, both directors typically have us glued to our seats, staring at the final credits in shock.

Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan tells the story of a sweet, already-grown-up ballet princess (Nina Sayers) who lives at home with her mother, Erica; Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange shows us a youngster (Alex DeLarge), who leads a street gang, with an incredible aggressiveness but also great intelligence and “manners”.

At first glance, we can immediately see in Black Swan the Greek myth’s characters of Clytemnestra, Electra, and The Women of Trachis (as done by Sophocles), giving us our first Freudian hints; an absent father, a controlling and overprotecting mother who embellishes her daughter’s adulthood with fantasies while minimizing her character, and her insecure and fragile child who silently resents her attentions. This sneaky war between them and the rhythm of music feeds Nina’s Black Swan persona, For Alex DeLarge, it is the same… more or less.

Nina and Alex seem different and distanced one to another, but they have in common several things; control and desire thrive beneath both protagonists, and classical music is their way for controlling and repressing their true desires and inner selves. It is through Tchaikovsky that Nina finally lets herself go, while Alex DeLarge uses Beethoven (and several artistic references) to purge what he deemed necessary to be purged; both share the similar self-destructive drive which –knowingly or not– communicates to the outside world strictly by –and with, and for– art.

And art, indeed, has been our way to express what our souls need to say; it’s a great communication tool. What makes us “different” among our fellow fauna, is our ability to voice what in nature is voiceless; to create words which serve us, among other things. To state, declare, argue, and ultimately, to import from our mind’s ideas and emotions.

Linguists and psychologists can agree that, without speech (in any way or form) our evolution could be perceived as senseless. Our throats evolved to be controlled, our mouths to articulate, and our brains to create that first syntagma that by any means necessary found its way to be interpreted by whoever we wish, because our will is, by far, our greatest tool –and our greatest flaw– for communication.

3. Where The Wild Things Are (2009, Spike Jonze) & 4. The Science of Sleep (2006, Michel Gondry) & 5. Eternal Sunshine of The Spotless Mind (2004, Michel Gondry)

From childhood we are taught that dreams are a collage of complicated images and symbols, composed by a series of ideas that somehow are related to our experiences, but that, at the end, we are told are mere fantasies.

Our first approach to that field is then influenced by the never-ending speech our parents recited: “Dreams aren’t important, nor real”. So, time passed, and all those dream-dilemmas were boxed, kept outside our recent memories, and substituted by brand new definitions of what compose them.

It is, indeed, in the Realm of Morpheus where our minds speak to us in the most peculiar ways, giving us signs and maps about who we really are, and what we really feel. Where The Wild Things Are, The Science of Sleep and Eternal Sunshine of The Spotless Mind show us that indeed, in some place around our heads lies eternally a bunch of unconscious imagery waiting to be unlocked, to be freed.

In these three films, the protagonists (Joel in Eternal Sunshine; Max in Where the Wild Things are; and Stéphane, in The Science of Sleep) find themselves exploring a surreal realm, where what was conceived as real no longer seems to be, or doesn’t matter anyways. Our heroes are, each one in different levels, discovering what is hidden in their minds. The role of that inner child, which symbolizes curiosity, is what moves the plot in the films forward.

What once was forgotten, now, for each of them, reemerges, and as an old wine gets stronger than in its first day, their unsolved issues come back with a bang! The process in which we learn –or need– to forget comes with adulthood (Joel), but still being adults, we can be tricked and seduced to feed our dreams and transform them into our reality (Stepháne).

Perhaps the already so mentioned inner child needs a certain balance between forgetting and dreaming, so we can deal with what life has for us (Max), or better yet, to what we have for life. Andy Warhol said once that everybody must have a fantasy, and he was right. To cope with the world, our brains somehow need to discharge all the content they have underneath, the in-between lines, what’s hidden from us, and as an overflowing dam, there are times where we need to let the water flow and cover it all.

In this sense, the notion of interpersonal communication provides psychologists a concise notion for interpreting human thoughts and behaviors, sending light to that –at times– dark corridor of our personalities.

One of the greatest enigmas –for Freud– were two particular mythological creatures; the son of Aphrodite, a winged, mischievous child called Cupid, who in his adult-form, was a beautiful man with butterfly wings, Eros; the other one is defined as “benevolent death by a tender touch”, Thanatos, the original Grim Reaper.