Jacques Derrida was a French philosopher, particularly well known for his analysis of the semiotics of western culture through the lens of deconstructionism. Derrida is well-known as one of the most formative figures in post-structuralist and postmodern thought, as well as one of the most innovative thinkers of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Through his analytical framework of deconstruction, Derrida was able to form an attempt to decodify the nature of culture’s use of symbols; aphorisms, and practices to delve deeper into the underlying consciousness of society and by extension, the underlying consciousness of individuals.

Derrida contributed significantly not just to our understanding of the philosophy of mind but also to our understanding of law; anthropology, gender studies, sociolinguistics (the way sociology influences the linguistic makeups of cultures), architecture, ontology, epistemology and many other forms of thinking and creative work.

His best known and most widely read work, Speech and Phenomena, is also considered his most important. In it, he details his relationship to the philosophy of Edmund Husserl, a German philosopher who founded the school of phenomenology (the premise that reality is not independent of human consciousness and is in actuality based within human perception rather than outside of it.).

In Speech and Phenomena, Derrida elucidates his view that the communication of an idea in the form of language is in conflict with the expression of the idea and the indication of the same idea (logic vs. rhetoric). In this conflict, Derrida states that the meaning of language (in the form of an idea meaningfully expressed) is found in the expression of the idea, and not the indicators.

In this way, he confronts logic and rhetoric (which dominated the late 19th century and early 20th century philosophical societies/institutions of Europe) with a revival of western metaphysics (In the tradition of Kant, Berkeley, and early western Philosophers such as Aristotle, Plato and Socrates), which allowed Derrida to deconstruct Western culture and made its intricacies and what Derrida termed its “prejudices” (its tendency to hierarchize, centralize and patriarchalize thought).

In this way, Derrida allowed himself and those influenced by him (such as Spivak, and Catherine Malabou) to analyse the structures of Western philosophy and seek to understand the origins and genesis of these ideas. In doing so, Derrida and his students understood that there is an infinite complexity in the structure of the mind and that structures are inherently formed by their very genesis, and that these origins are external and unknowable to its observer (us as individuals.)

By deconstructing the definitions that were put in places to hierarchize chaotic structures (or what Derrida termed aporias), Derrida was able to analyze the symbology of words themselves and their intentionality, leaving behind the artificial structures generated during the analyses of these expressions that were created by philosophers of the past. He did not disparage these works or structures (too much!), but understood that through analyzing the structure of these structures, one could arrive closer to the heart of truth.

Below are ten films that can be read within the context of or were inspired by the philosophy of Jacques Derrida:

10. Rear Window (1954)

Though Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window debuted while Derrida was beginning to make his mark in philosophy, much can be said about Hitchcock’s understanding of the need for a deconstruction of Western culture’s inherent mythologies and predispositions.

This makes for a dichotomous sort of understanding of popular Western culture as Hitchcock began his career based on the tropes of western understanding of psychology, but also came to understand that these thoughts and suppositions were beginning a process of flux and change in the early 1950s.

What makes Rear Window a definite connector or perhaps precursor to what would follow (films that became to be directly influenced by Derrida’s overall influence on culture) is the fact that Hitchcock’s filmmaking itself began to become more deconstructive itself.

Hitchcock cast a former leading man, James Stewart as the less-characteristic introverted main character of the film, Jeff Jefferies. As Jefferies, Stewart seems to deconstruct his own persona, one which was based upon pre-1950s cultural and philosophical thought.

As opposed to his previous cinematic persona of “matinee-idol” style regular-Joe mannerisms (as depicted most iconically in Stewart’s performance as George Bailey in It’s a Wonderful Life), Stewart here seems aloof, conniving and secretive. In this way, Hitchcock seems to attempt to mask or obscure the true intentions of not only his main characters, but of the narrative of the film itself.

This sort of obfuscation is evident even within Hitchcock’s cinematography, where he favours long meditative shots, that seem to focus upon several things and nothing at once, creating an eerie atmosphere of unease.

This tension is unlike the tension of Hitchcock’s earlier films, where the focus is upon individual action, here by focusing on Jefferies’ obsession with surveilling his neighbours, Hitchcock seems to ask the audience to consider the nature of appearance (expressed by the seeming banality of urban life) versus the nature of reality (the confusion exhibited by Jefferies when this seemingly banal urbanity is disrupted by dissonant events).

In this way, the paranoia that Stewart embodies and that which Hitchcock attempts to portray is similarly analogous to Derrida’s notion that as opposed to a phenomenological understanding of reality (that human perception forms it), it is rather that our mind distorts the external events of reality to form a symbolical narrative that suits or pre-existing prejudices.

9. Rubber (2010)

Quentin Dupieux’s Rubber from 2010 is enigmatic in the way it deals with its underlying themes. Aside from an opening which announces the film’s intent as merely a fable where events happen for “no reason”, we’re thrust into a cinematic world where tires come to life and films are viewed through binoculars. Derrida wrote in Dissemination:

“A text is not a text unless it hides from the first comer, from the first glance, the law of its composition and the rules of its game. A text remains, moreover, forever imperceptible. Its laws and rules are not, however, harbored in the inaccessibility of a secret”

In this way, Rubber could be viewed as an expression of Derrida’s idea that a text can only be a text (or, in this case, that a film can only be a film), if it hides its own rules within itself. By announcing from the get-go that the film itself happens for “no reason”, Dupieux allows the film to exist as though it were its own living being. It offers no explanation for the life that is suddenly given to the tire, and in this establishes the rules of its own world.

8. Adaptation (2005)

Charlie Kaufman’s Adaptation is in of itself an intertextual odyssey, formed of equal parts fiction and reality. The film potentially serves as personal catharsis for Kaufman, but as do many of Kaufman’s films, Adaptation also serves as a sort of conduit for postmodern thought, at once condensed and expanded, like an undulating tide of ideas within his chosen medium.

In Adaptation, we can clearly see some of Kaufman’s postmodern influence which is typified in the writings of Derrida. In Without Alibi, Derrida wrote that:

“To tell the truth is, on the contrary, to say what is or what will have been and it would instead prefer the past.”

Throughout the film, we see Kaufman (portrayed by Nicolas Cage) attempt to adapt the real-life story of Susan Orlean’s non-fiction memoir and article series, “The Orchid Thief”. By recreating the past of someone else through his emotive perceptions and experience, we see Kaufman become immersed in the idea of telling the truth, though beset with anixety over the mixing of truth and fiction (lies).

By seeking out truth, Kaufman begins to feel as though people prefer not knowing or operating under the assumption of fiction. In this way, Kaufman is channeling many of Derrida’s thoughts on truth, particularly where it concerns personal and cultural truth. In Margins of Philosophy, Derrida wrote:

“Therefore we will not listen to the source itself in order to learn what it is or what it means, but rather to the turns of speech, the allegories, figures, metaphors, as you will, into which the source has deviated, in order to lose it or rediscover it—which always amounts to the same.”

By analyzing the subliminality or subcontextual nature of the story, we find that Kaufman’s rendering of the adaptation of the film by comparing it to his struggles with adaptation allows us to better emote and understand the truth of the story. The impact here, not being that we relate to the story as presented, but rather we relate to what the film hides within its text.

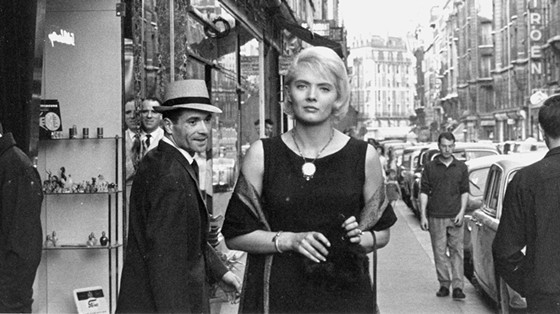

7. Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962)

Agnes Varda’s Cleo from 5 to 7 is notable for a variety of reasons, in particular it was one of the first French films of the 1960s to depict the then-burgeoning culture of urban French Feminism and the film is also hailed as one of director, Agnes Varda’s most important and artistic works. Its relation to Derrida is notable in that Varda was known to be an admirer of Derrida’s philosophy and her films are widely infused with extrapolations, expressions and homages to his ideas and sentiments.

Particularly in Cleo from 5 to 7, Varda focuses on the nature of expressing our experiences of existence and our individual occupation with our knowledge of death, which were topics that also were of concern to Derrida. He wrote in Aporias:

“‘My death’ in quotation marks is not necessarily mine; it is an expression that anybody can appropriate; it can circulate from one example to another.”

It is in this way that Varda so tackles the nature of death as a philosophy of communal. Throughout the film, we see Cleo, the main character begin to wash away the excesses of her identity until she is filtered down to the nearest expression of her truth, By depicting an awareness of death as a “stripping away”, Varda is echoing Derrida’s understanding of death as an implication rather than a position.

The implication of course is that death comes to us all in the same way, a sentence that we can all appropriate and will all experience. This is not necessarily something that is to be thought of as grim or foreboding, but rather an interpretation of the external reality of consciousness, or perhaps more succinctly, the fact that our consciousness will end despite our protestations.

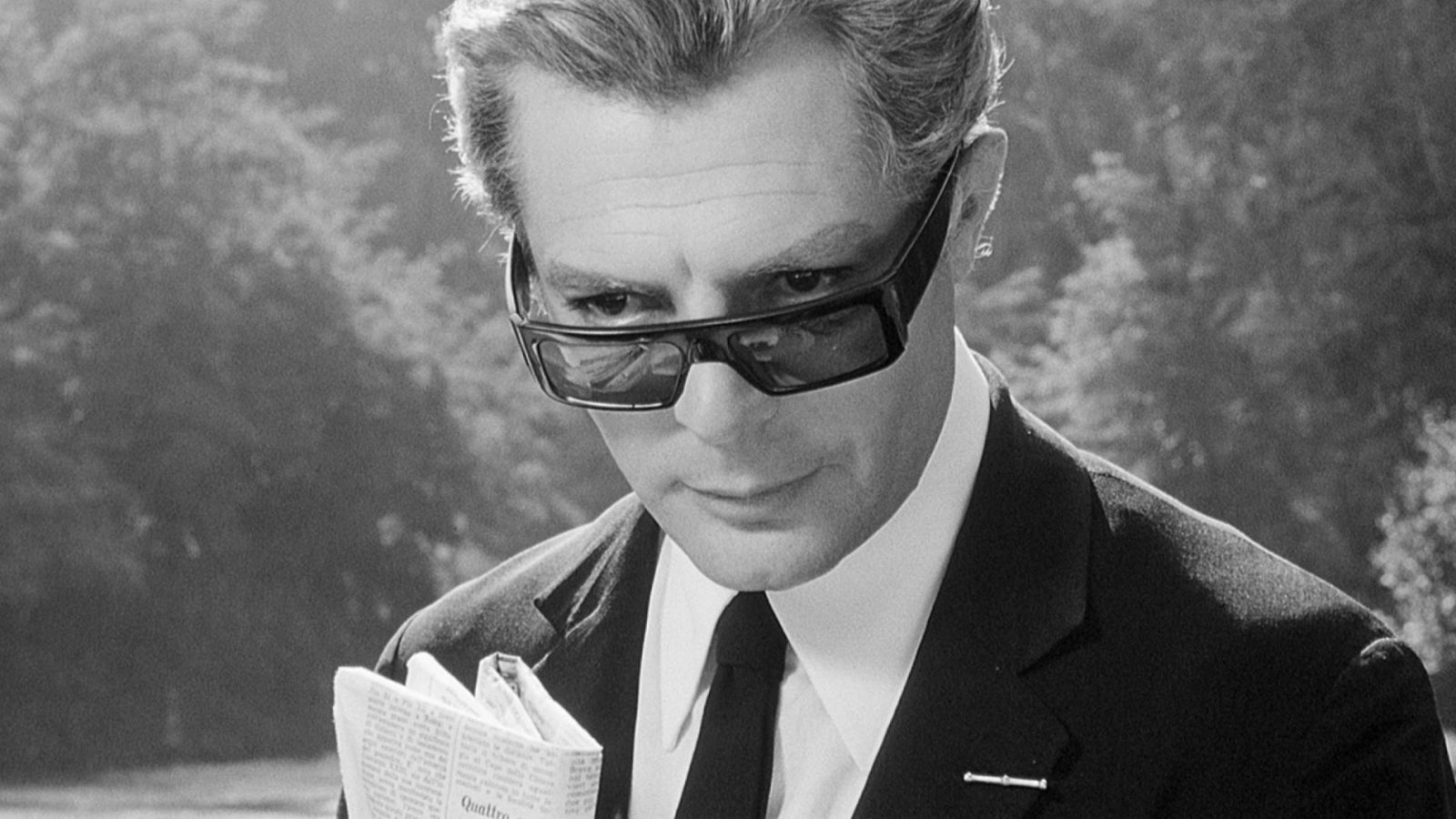

6. 8 ½ (1963)

Fellini’s 8 ½ is a masterpiece of cinema, both in form and in its text, however aside from its critical acclimation, we can also see the sneaking inkling of Derridean philosophy hiding within its subtextual structure.

The film is somewhat of a self-reflexive treatise on the nature of creativity and the pressures which are put upon creatives to design something that can be related to as evocative, profound or moving. It details the stresses of creating such a work. By subverting the traditional way these sorts of stories are told, Fellini is able to dig at a deeper meaning that is somewhat hidden by structures designed to mask the truth of a reality (as Derrida states in Speech and Phenomena).

Fellini’s use of humour in serious circumstance and the nature of Guido Anselmi’s (played by Marcello Mastroianni) fantasies, is an attempt by Fellini to circumvent the illusion of phenomenology and hint at the deeper meanings hidden within the abstractions of thought and dreams.

By merging reality and dream-logic, Fellini perhaps comes close to the post-structuralist model described by Derrida in Of Grammatology: “There is no outside-text.” This is not to state that nothing exists outside of language, but rather that everything that is expressed in grammar (whether it is expressed in internal logic or communal language) is existing within itself within a sort of cyclical lifecycle.