6. The Life of Juanita Castro (Andy Warhol, 1965)

Andy Warhol is one of the most widely known artists throughout history. Starting as a commercial artist, Warhol had a heightened awareness of mass media and advertisement that translated to his artworks, and in turn his films.

Warhol’s earliest films were centered on lengthy duration and silence, including a film that ran just under six hours of a man sleeping. A minimalistic influence was still present over his more structural films, including The Life of Juanita Castro.

In The Life of Juanita Castro, playwright Ronald Tavel reads out lines to a group of actors in a family portrait-like arrangement, mimicking the rows of bottles seen in Warhol’s Green Coca-Cola Bottles (1962).

The stationary camera is diagonally angled towards the group as they reiterate the words of the playwright. The film, which carries the essence of a theater performance, is inspired by Fidel Castro’s sister, Juanita, who abandoned from Cuba for the United States.

Warhol, the face of the Pop Art movement in the United States, made Pop principles present in his films. He bolstered the significance of familiar objects and people. He focused on the treatment of his subjects as opposed to their individual identities.

The serial manner in which his subjects, including Jackie Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe, were presented rendered them void of individual character, rather facilitators of ideas, including celebrity and immortalization.

In The Life of Juanita Castro, the iconic names of Juanita, Fidel, and Raul Castro, as well as Che Guevara are treated with unfamiliar faces. The characters’ automatic repetition of fed lines leaves the words lacking substance, more emphasis is to be found in the manner in which they are presented.

7. Wavelength (Michael Snow, 1967)

Canadian born Michael Snow began his career as a painter and sculptor and later moved into video and film-based work. Snow’s work gained traction after the release of Wavelength. Wavelength is forty-five minutes of a studio loft, sprinkled with gradual zooms and color changes.

A cast of characters occasionally appears throughout the course of the film, but the camera does not engage with them. The camera is void of a human touch, merely a mechanical recording device. It holds no emotional ties to the characters, even in the face of death. Amidst little content, the filmmaker’s presence is silent. Instead, the audience is thrust into the role of being an active viewer.

Snow asserts knowledge of the elements of art while emphasizing the distinct qualities of film in Wavelength. Color use is blatant, seen in unsettling tinting techniques. Spatial awareness is asserted through carefully planned zooms around the loft. In Wavelength, sound, a distinct quality of film as opposed to painting, is characterized by a continuous sine wave.

Michael Snow was especially inspired by the work of Paul Cézanne. Cézanne believed the Impressionists that came before him did not put emphasis on the structural qualities of painting. He analytically broke nature down into the elements of art, including line, shape, and color.

Both Cézanne and Snow achieve balance in their work by molding the physical elements of a space into a more illusionistic environment. Like Cézanne, Snow uses a structural style in Wavelength, pronouncing more importance in its form, as opposed to content.

8. Eraserhead (David Lynch, 1977)

David Lynch studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Boston and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts before pursuing Avant-Garde filmmaking. His paintings are dark, melancholy, and convey a sense of impending doom, all of which are themes incredibly evident in his films, specifically Eraserhead.

Eraserhead is an exploration of the fear that plagues Lynch’s paintings. The atmosphere of the film is built on white noise, a grim industrial town, and an unwanted pregnancy that leads to a horribly deformed baby.

The urban settling is illustrated as a place of alienation, loneliness, and filth, possibly informed Lynch’s own experiences living in cities. Eraserhead is a balance of the conscious and subconscious telling of a story that lacks rationality, but gains reliability through the use of a protagonist and dialogue.

Lynch’s paintings and films parallel the work of visual artists including Francis Bacon and Isabel Nicholas. The film explores the condition of the industrial environment, just as Metropolis (1927) did, while also evoking the discomforting quality of the imagery of Un Chien Andalou (1929.)

Dually, Eraserhead’s nightmare sequence harkens back to the irrationality of the Surrealists’ translation of dreams. Seeing as he served as the writer, producer and director, Lynch is marked as an auteur in Eraserhead. Lynch’s overt control over the film parallels the control artists have over their canvases.

9. Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders, 1984)

While initially studying medicine, Wim Wenders felt a yearning to paint and dropped out of school to pursue art. Initially, Wenders separated his photography from art-making until he began using the camera as an extension of painting to capture a moment in time.

Soon after, photography served as a transition into filmmaking for Wenders. He found himself fascinated with the construction of time through juxtaposition of photographic stills and narration became inevitable.

Wenders finds that the frame serves as a crucial role in the beauty of a painting. Everything held within the boundaries of the frame is correct, leading to the conclusion that there is beauty in organization. The importance of framing united Wenders’ paintings, photography, and film.

The subject matter of his paintings consisted of nature, landscapes, and cities which later became central themes of his films. In his transition to filmmaking he used these themes as instruments in character study, just as his favorite artist, Johannes Vermeer, used setting to explore the states of his subjects.

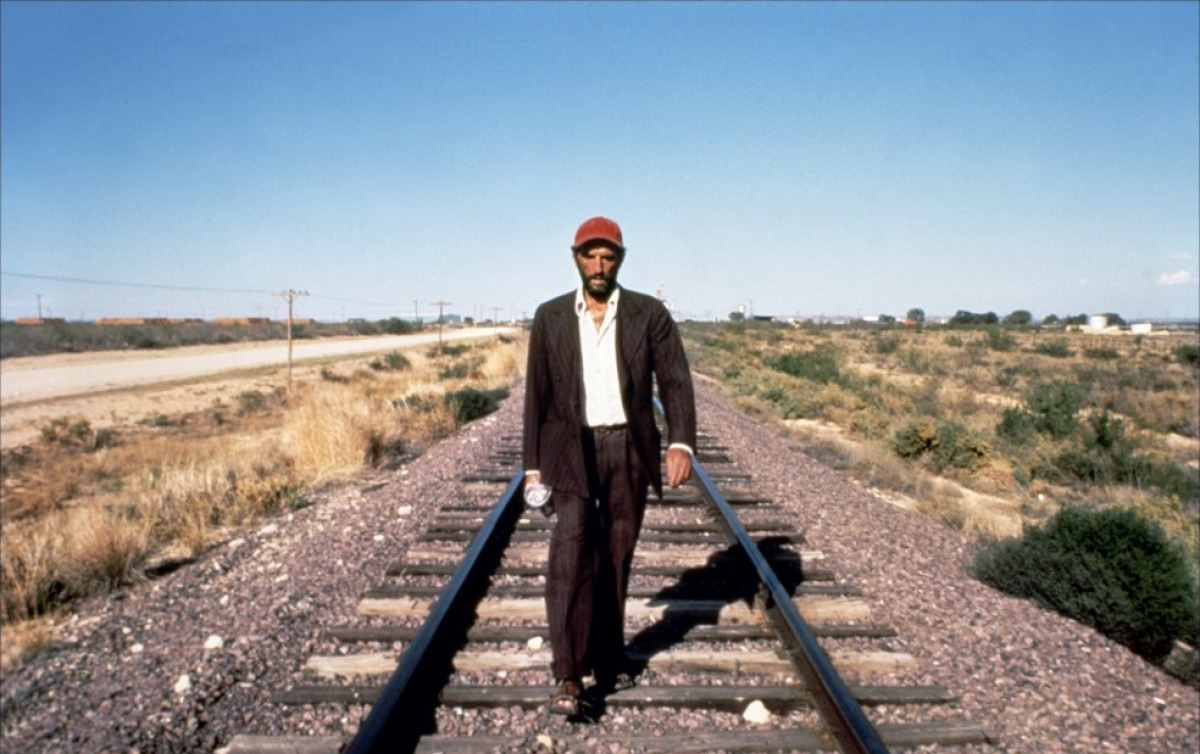

Paris, Texas is the study of a man reconnecting with his past, through his son and wife. The subject matter of Wenders’ landscape paintings becomes evident in the opening of film as Travis (Harry Dean Stanton) moves amongst the desert landscape in his red cap. In order to grasp the landscape, Wenders took color photos of the American West before shooting the film.

Paris, Texas reflects understanding of the use of color, an essential element of art. The film reflects Wenders’ goal of composing time and narration through a series of frames is supported by a deep study of characters and location.

10. The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (Julian Schnabel, 2007)

Julian Schnabel began his art-making career with a solo show at the Mary Boone Gallery in 1979 and later began filmmaking when he co-wrote and directed Basquiat (1996), a logical translation of fine art to film.

As a painter he was primarily know as Neo-Expressionist. His work was characterized by the gestural application of paint alongside figures, as well as non-traditional materials.

Schnabel’s paintings came after a time of high intellectualism in art, specifically in the works of Minimalism and Conceptualism. He rejected these highbrow movements for art-making that got to the source of the emotional human experience.

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly is based on the true story of Jean-Dominique Bauby, the Elle Editor who suffered from Locked-In Syndrome after a stroke, leaving him fully paralyzed, with the exception of his left eye.

The film is composed of shots that capture the emotional energy that pairs with the immediacy of painting. Schnabel identifies himself primarily as a painter, as opposed to a filmmaker, but the conversation between his canvases and films is evident. Religious iconography played a role in his work as a painter and continues be a theme in The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.

In the film, a trip to Lourdes, France and an emphasis on a Virgin Mary statue illustrates religion as a source connection for the audience. Each and every component of the film contributes to the goal of emotional depth.

Fantastic elements are mixed within biographical information in order to convey a sense of a relatability to a condition with extreme rarity. Many of the shots come from Bauby’s point of view, leaving them blurry and semi-conscious at times.

These shots mimic the more gestural application of paint on Schnabel’s paintings, emphasizing the trapped confusion characterizing Bauby’s emotional state as opposed to capturing the scene purely for its physical setting.

Author Bio: Emma Roberts is an art history major at Temple University in Philadelphia, PA. Her primarily concentration is on modern and contemporary art as well as curatorial practice. In addition to art history, she loves films, specifically films of the French and Czech New Wave movements.