5. Looper (2012)

Sci-fi, or “tech noir” has had a relatively niche market within the grander scheme of onscreen crime, dating back to trailblazers like Blade Runner (1982) and, to a lesser extent, Alex Proyas’ Dark City (1998).

The trick is to invent a world that simultaneously looks backwards and forward, finding the gritty crevices in between and blowing them up to levels that speak to current day audiences. Looper, the hitman thriller from writer/director Rian Johnson, does just that, with a particular eye towards forgotten gems like Murder by Contract (1958) and Blast of Silence (1961).

The assassin in question, known only as Joe (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), makes a living by knocking off guys sent from the future. In that, he closes the loop of their existence – hence, “Loopers.” Unfortunately, the professionalism of this practice is thrown into a tailspin when the next target turns out be his older self (Bruce Willis), sent back to 2044 to settle an old score.

It’s a heady concept without a doubt, but one that’s tackled head on by Johnson’s penchant irony and acknowledgement. The interactions between both men, or, the same man, technically, folds the hitman stereotype back onto itself, enforcing an existential bend that’s rarely approached in the genre.

Willis brings the goods as a decaying murderer, but it’s Gordon-Levitt who disappears into the role with reckless abandon, enhanced by eerie makeup and a spot on vocal impression of the Die Hard star. Surrounded by a cast that includes Emily Blunt, Paul Dano, and Jeff Daniels, Looper compensates for its small scale science fiction with a poignant attention to anachronistic detail.

Rian Johnson, who appeared on the scene with his high school mystery Brick in 2005, continues to blur genre conventions in the modern age. The “Gat Men” that embody the mob in the film are pulled right from the pages of a 30’s Black Mask Magazine, while the blunderbuss weapon of Joe’s choice implies an era even further away than that.

Each choice made on the part of production design or the lead character lends another layer of contradiction within an old timey future. Joe may have lived long after The Killers (1964), but his conscious decision to dress in their image is symbolic of a future that not only idolizes noir, it behaves in their forlorn footsteps.

4. Drive (2011)

Like Le Samourai (1967) before it, Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive is at its best when functioning as a film noir fashion statement. The fuzzy neon nighttimes, the synthpop soundscapes, and the violent extremes that could double as the greatest ever infomercial for style comprise a story that’s been done time and time again.

Melville did in in the 1960’s, Walter Hill in the 70’s. And while this pensive piece of arthouse pulp may not outrank those influences, the case made is pretty strong.

Refn, a filmmaker who has received equal parts praise and scorn for his emphasis on gratuitous content, turns the intolerance levels up to ten. Foreboding is a powerful emotion to evoke in a viewer, and he takes delight in spinning the framing, lighting, and inflection of each line to create a flinch of unease at every turn.

The dialogue isn’t exactly the stuff of pulp excellence, serving merely to provide information to get to each the viewer to each visually jam-packed scene – but once there, the director knows only too well how to maintain interest. The driving scenes are stupendously exciting to look at, constantly underplayed by the indifferent stare of its operator (Ryan Gosling) while L.A. lampposts look on.

The acting is distant to say the least, but performers as talented as Albert Brooks, Ron Perlman, Bryan Cranston, and Oscar Isaac are there to speed up the emotional stalling. In a way, getting to see each men tackle such empathetic material is a bit of a thrill within itself.

Carey Mulligan is passable in the ingenue role, showing some true sparks of fear only when Gosling smashes a goon’s face in (literally) between elevator rides. And Gosling, leading the way as the unnamed Hollywood stuntman, gives one of his more celebrated turns in front of the camera – a bit of an acquired taste, but perfect when matched with Refn’s other stylistic ingredients.

As a crime film, it’s arguably one of the most iconic entries of the 2000’s, a testament to its head turning minimalism and sexy danger. And what’s neo-noir without a little sex appeal?

3. Nightcrawler (2014)

Very much cut from the same saturated cloth as Drive, down to mutual producer Michael Litvak, Nightcrawler is Ace In The Hole (1951) for the iPhone generation. Only instead of Kirk Douglas’ cleft-chinned schmoozer, viewers are left with Jake Gyllenhaal’s sociopathic camera man.

The actor, man-bunned atop a set of saucer eyes that refuse to blink, gives the performance of his career as Los Angeles loony Lou Bloom; freelance recorder for news producer Nina Romina (Rene Russo). Bloom’s got an unnatural talent for capturing crime scenes, but what she doesn’t know is that he also has a knack for artificially creating them…

As a narrative, Nightcrawler is very much a one trick pony. Taking cues from the works of nihilists like Jim Thompson and James Ellroy, screenwriter Dan Gilroy wastes no time trying to conjure up empathy for Bloom, who practically oozes pleasure at being a repulsive human being.

The script not only tosses out opportunities for the character to redeem himself, but instead offers chances to further his sickening sociopathic behavior. Most frightening, however, is Gyllenhaal’s portrayal, so thoroughly smarmy in its professionalism it makes things sound practically logical by default.

Sharing many a tendency with Gosling’s no-name driver, Nightcrawler shows what an unstable psyche would manifest as if a sudden interest in fast talk was introduced.

First time director Gilroy flashes an immense appreciation of 80’s neon-noir, with Bloom’s cherry red muscle car speckling across the frame like Satan’s personal publicist.

From the gory mansion shooting to Bill Paxton’s disturbing demise, each of the character’s so called “assignments” come off as voyeuristic and slathered in sleaze – the kind of psychological residue a shower can’t get rid of. This sleek journey also provides one of the list’s more topical tales; that of media and the sensationalism that runs nightly news.

By no means based on a true story, the film nevertheless spends each frame reminding the viewer that men like Lou Bloom do exist; and they make a living out of the noir recurring daily outside our bedroom windows.

2. Glass Chin (2014)

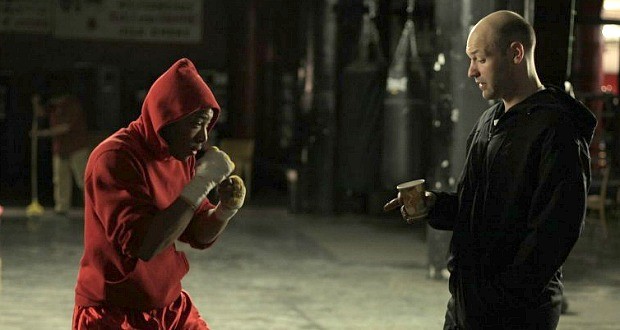

Glass Chin is a simple movie about a simple man, washed-up boxer Bud “The Saint” Gordon (Corey Stoll). Like the athletic losers before him, the charms of the mob prove too great to resist, and the resulting fall from a not-so-great existence is swift and ugly.

But if there’s one thing that film noir proves time and time again, it’s that execution is often the greatest asset a filmmaker can possess. Such a theory is in full effect here, courtesy of brilliant writer/director Noah Buschel.

All the typical archetypes are honored, with Stoll giving his best John Garfield impression opposite Billy Crudup, who has way too much fun as a Paul Stewart dandy with insane levels of self-satisfaction.

Yul Vazquez also pops up playing an enforcer with a stressed emphasis on Twitter followers, contrasting Bud Gordon’s affinity for the Walkman and old school tunes; the latter of which comes to glistening realization in the opener, where Bud sprints down the street to Laura Nyro’s “Gonna Take a Miracle” cover.

This joke comes back around with topical glee later on, both a nod to the late great singer and an indicator of Buschel’s singular ear for originality. As far as the written word goes, Glass Chin is a stellar display of small scale exaggeration, the kind of story that sounds like David Lynch and looks like Wes Anderson.

These visual touches arrive with particular complexity, splitting the story’s color scheme into moral palettes: autumn reds for good, nighttime blue for bad. Paired with the director’s knack for unconventional camera placement, especially the bedroom confessional between Gordon and his girl Ellen (Marin Ireland), and Glass Chin offers an incredibly refined alternative to films like Drive in the arena of “arthouse neo-noir.”

Buschel, a Philadelphia filmmaker who struck noir gold once before with his 2009 effort The Missing Person, is rapidly approaching the status of unsigned hype within the film industry. If efforts like this continue to arrive with such fully formed creativity, it’s the beginning of a crime drama career for the ages. If not, then at least viewers have this delicate slice of delicious crime to remember him by. Laura Nyro references and all.

1. Inherent Vice (2014)

Inherent Vice is a masterpiece. There will be those who groan at its off-the-wall complexity and A.D.D. narrative, but those naysayers have clearly never read the works of author Thomas Pynchon. His 2009 novel of the same name is a labyrinth of density and inside jokes, barely holding together to compress a coherent book, let alone a film with a decent runtime.

But Paul Thomas Anderson isn’t your typical studio director, he’s a man who’s conveyed everything from the porn industry to oil mining with the excessive control of a mad genius; each time slipping in and out of stylized hats like a chameleon with a camera. Consequently, Inherent Vice doesn’t just work, it explodes off the screen with the pulsing color of a kaleidoscope constructed from cotton candy – whatever the hell that means.

This P.T.A. joint finds stoner P.I. Doc Sportello (Joaquin Phoenix) knee deep in radicals, land tycoons, and saxophone sporting informants off the coast of California circa 1970. It’s a swinging time for everyone, except seemingly, former flame Shasta Fay (Katherine Waterston), who pines for Doc’s help in tracking down current hubby Mickey Wolfmann (a stubbled Eric Roberts).

Phoenix is fantastic in the role, fixed with a permanent look of confusion while seemingly being the only guy who can put two and two together. Everyone else, from cop “Bigfoot” Bjornsen (Josh Brolin) to snide D.A. Penny Kimball (Reese Witherspoon) is too busy poking fun at the dirty hippy to see the stars from the pot-laden trees.

Other notables that pop in include Benicio del Toro, Owen Wilson, and Martin Short; who has way more fun being a doctor than most licensed physicians are legally allowed. Through it all, an adapted screenplay packed to the roll with inside jokes (hey, James Wong Howe) and West Coast references keep things higher than, well, anyone in this film really.

Anderson’s admitted influences for the film are as notable as they are wide-ranging, jumping from everything to The Big Sleep (1946) and The Big Lebowski (1998) to The Long Goodbye (1973) and Up In Smoke! (1978). Amazingly, the thread of each is done justice in the final product – particularly Goodbye, a long treasured mystery from Anderson idol Robert Altman.

It’s tough not to rant on and on about the film’s quality, or how frustrating it is that it fell short of making back its measly $20 million budget, but time, as has always been the case, will prove kind to the films that deserve it. In the meantime, Inherent Vice is the neo-noir to beat going into the second half of the decade.

Author Bio: Danilo Castro is a freelance writer and editor of the Film Noir Archive blog. He has contributed and reviews to several publications including PopMatters, Noir City, and CinemaNerdz, spending much of his time watching classical Hollywood cinema. But if its not, that’s okay too.