5. Faye secretly enters Cop 663’s house (Chungking Express, 1994)

In a sequence of scenes edited into one, the camera follows Faye into Cop 663’s house where she proceeds to tidy up and do various chores. She does not stop there, however. She puts sleeping in his bottled water to prevent him from going out at night, she checks his wallet, she examines his bed with a magnifying glass for other women’s marks, and she even changes the etiquettes of his sardine cans. A cover of The Cranberries’ “Dreams” with Faye Wong on the vocals is heard throughout the sequence’s duration.

The sequence is probably the most romantic in the whole film, exemplifying the unrequited love Faye feels for Cop 663 and the extremes she is willing to reach in order to care for and learn of him, despite the fact that he does not have a clue about her feelings. Faye Wong appears utterly adorable through her mischievousness.

4. Cop 663 and Faye meet (Chungking Express, 1994)

Cop 663 enters the shop where Faye is working and asks for a chef salad. She prepares it while dancing to “California Dreaming” by The Mamas and the Papas.

The event occurs at night and Wong Kar-wai presents it through the perspective of Faye, who watches Cop 663 approach. She dances to the song and appears somewhat disinterested. However, the narration has already informed the spectator that she will fall in love with her customer, giving the scene a whole other meaning, as she states that she likes loud music because it prevents her from thinking.

The use of the particular song symbolizes the Westernization Hong Kong has experienced through the decades, with the protagonists having grown up with Western cultural influences. It also states the twofold nature of Hong Kong, which lingers between the English and the Chinese.

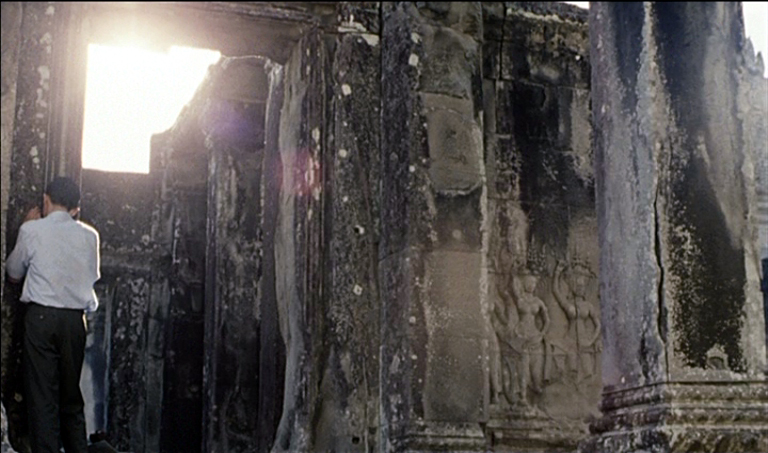

3. In the last scene of the film, Chow Mo-wan whispers in the wall of a temple (In The Mood For Love, 2000)

Mo-wan finds a hole in the wall of Angkor Wat. Initially he places his finger in it and then he puts his hands together and whispers in the hole while a monk is watching him. He then leaves through a corridor while the camera takes a tour inside the temple.

The things left unsaid are more important than what isn’t in this particular film, with silences, glances and body language proving much more powerful than words. This tactic is exemplified in this scene, where Mo-wan pours all his frustration and anguish over his relationship with Li-zhen into a hole. However, as is the case with most of the film’s plot, Wong lets the audience decide what is being said. The same applies to his feelings of loss and despair, which are communicated through the intense score, in a scene devoid of words.

As the camera lingers behind the monk’s head, depicting Mo-wan from above, the cinematography again gives the impression to the spectator that he is secretly peeking at the scene.

2. Bai Ling talks with Chow in her room, after they had sex (2046, 2004)

Bai Ling lowers herself in order to keep Chow with her, stating that she does not care if he has other women, as long as he treats her differently. However, Chow’s womanizing nature and egoism appear along with his sarcasm, and eventually Bai Ling breaks up with him.

Wong Kar-wai presented in this film a technique where a shot within a scene stands apart visually from both the preceding and the following shots, depicting its own mood and emotions. In this particular scene, there is a sequence of similar individual shots where each actor faces right on the screen, despite the fact that they are actually opposite.

Furthermore, this is probably Ziyi Zhang’s best scene in the movie, since her reluctant but obvious feelings for Chow are more evident than ever, as she tries to retain her dignity while she actually fully surrenders herself. Wong took advantage of her prowess with many zoom-ins on her face.

1. Su Li-zhen and Chow Mo-wan decide to part ways (In The Mood For Love, 2000)

The two of them wait for the rain to pass together, since Su Li-zhen does not want to take Chow Mo-wan’s umbrella, fearing that the neighbors will realize they were together. When the rain stops, she asks him to part ways, since her husband has returned. He agrees.

Both of the cinematographers, Christopher Doyle and Mark Lee Ping-bin, present shots that appear as if the camera is peeking in on the action while it frequently moves in slow motion. This tactic finds its apogee in this scene, as the protagonists are being watched initially from behind a corner and then from a barred window. Furthermore, when he touches her hands, his move is presented in slow motion.

In another cinematic tactic, the scene is not presented in chronological order, with the most important moments inserted randomly in the timeline, as is the case with Li-zhen’s crying and her exit.

Maggie Cheung’s performance and style also reach their apogee in this scene, with her looking gorgeous in her Mandarin dress as she eventually bursts into tears, despite her efforts to appear strong and detached.

Author Bio: Panos Kotzathanasis is a film critic who focuses on the cinema of East Asia. He enjoys films from all genres, although he is a big fan of exploitation. You can follow him on Facebook or Twitter.