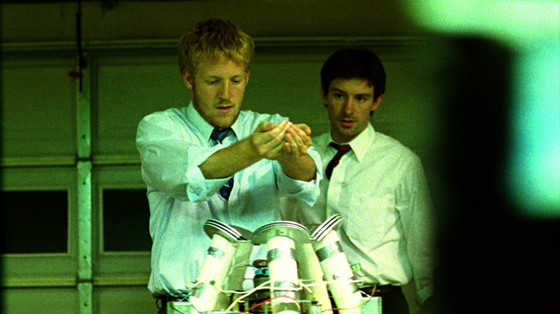

5. Primer

Having a degree in mathematics and being a former engineer, director Shane Carruth is probably one of the few people capable of completely understanding the concepts behind the time machine in “Primer”.

The technical dialogues, however, are not there to be understood so much as they are there give a sense of realism to this hard sci-fi picture.

The machine – basically a box – was accidentally invented during the development of a weight-reducing device. Initially astonished by their achievement, Aaron and Abe, two engineers who supplement their daily jobs with technology side projects, soon start exploiting it for profit by making same-day stock trades, but as their ambition grows, so do the consequences of their acts.

Despite its very limited budget, “Primer” won the Grand Jury Prize at the 2004 Sundance Film Festival. It is a challenging film, with mind-wrecking ideas that leave you wanting to watch it again as soon as it ends.

Aside from exploring the paradoxes of time traveling (which it does masterfully), it also deals with aspects of human nature; despite knowing the risks, it is almost impossible for the characters to limit themselves to hiding in a hotel room and stock trading when the possibilities of such a device are infinite.

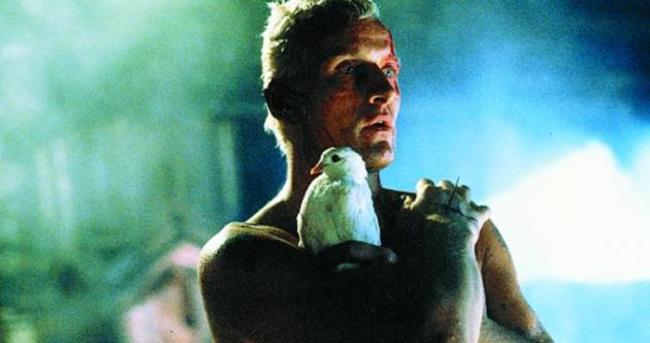

4. Blade Runner

Based on the book “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”, “Blade Runner” was the first of a series of Hollywood adaptations of the novels by Philip K. Dick.

In the now not-so-distant future of 2019, man has developed advanced biological engineering technologies, which led to the development of Replicants, artificially-created humanoids with capabilities beyond that of normal humans, but with very limited lifespans.

Replicants are banished from Earth, but are extensively used as workers in off-Earth colonies. Those who defy the ban and return to Earth are hunted down and promptly executed by Blade Runners, special police operatives set with this task. After a mutiny in one of the colonies, four replicants come back in order to meet their creator.

Rick Deckard, a former Blade Runner, is called back from retirement to chase them. While tracking them down, Deckard comes across Rachael, a replicant with implanted memories who believes to be human. As he eliminates the replicants one by one, Deckard starts questioning his own humanity.

Set in a futuristic yet decrepit Los Angeles, Ridley Scott’s masterpiece deals with themes such as the nature of humanity, the implications of technology in society, and the ethics of genetic manipulation and human ownership of other life forms.

Its film noir cinematography adds to an atmosphere of uncertainty and contradiction that leads the audience to question what it means to be human, just as Deckard questions his own nature.

3. Solaris

Based on the homonymous novel by Stanislaw Lem, “Solaris” depicts the mission of psychologist Kim Kelvin, who was sent to a space station orbiting the planet Solaris, where its crew has been experiencing hallucinations and psychological distress. Upon arrival, Kelvin soon starts experiencing the same symptoms, which are somehow related to the mysterious planet beneath them.

“Solaris” is considered one of the greatest science fiction films of all time. It is Russian cinema at its best, with long takes, laconic dialogue, and fantastic elements used to convey philosophical ideas about grief and our ability to communicate.

One of Tarkovsky’s motivation in making “Solaris” was to add greater intellectual and artistic depth to a genre he considered shallow (even after Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey”).

The film’s ending scene, for instance, is inspired by Rembrandt’s painting “The Return of The Prodigal Son”, which gives an idea of the amount of artistic references and ideas contained in this picture.

Challenging but captivating, “Solaris” is unbounded by the genre’s traditional conventions, and uses the sci-fi setting as a way of exploring human dilemmas.

It touches upon questions such as whether to live in a happy illusion or a hard reality, themes that would later be approached by “The Matrix” and “Inception”, but in “Solaris”, this question arises from the conclusion of a much deeper analysis, involving the grief Kelvin faces from leaving his father on Earth and his hallucinations involving his deceased wife.

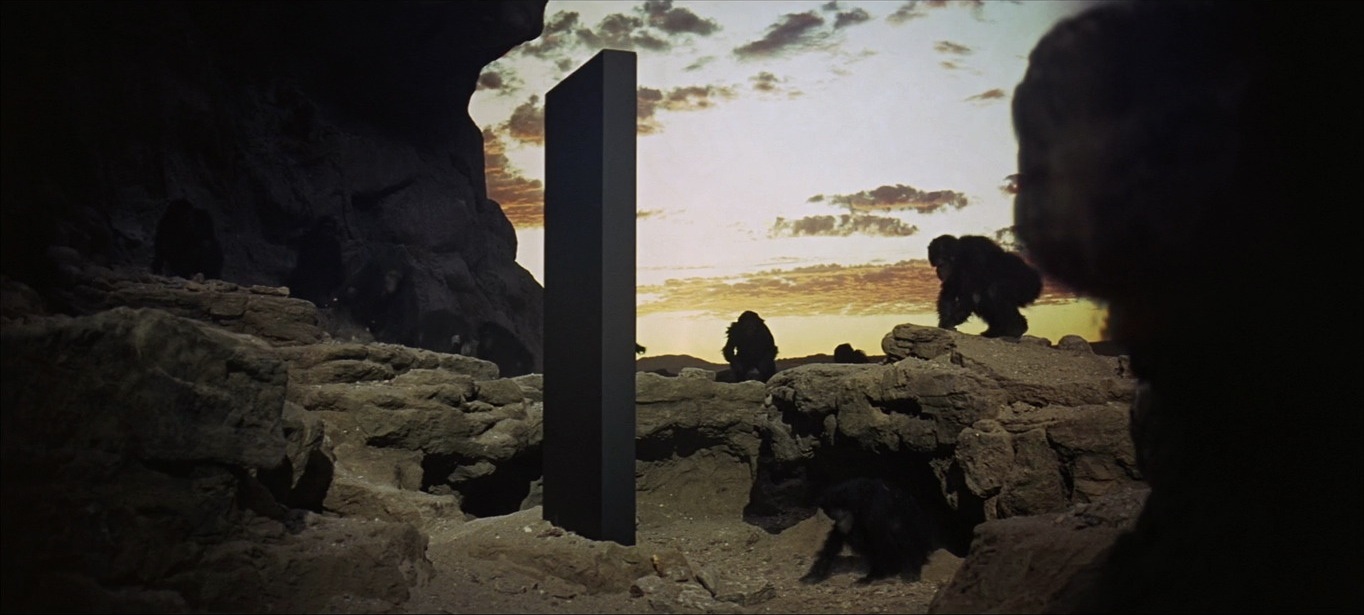

2. 2001: A Space Odyssey

Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” is one of the most influential sci-fi films ever made. Despite its almost universal acclaim, some critics have considered it too abstract and lacking dramatic appeal.

Indeed, it does not have the emotional depth of other ambitious sci-fi films, such as “Solaris”, but its stoicism plays a big role in making it hypnotic, a quality for which it was highly praised. The comparison with “Solaris”, however, is not strictly fair, as they deal with different subject matters, the latter focusing on human emotions and the former on artificial intelligence, human evolution, and existentialism.

It’s no simple task to summarize the film’s plot, but it can be regarded as take on evolution, and how technology is inserted in this process. The film begins depicting a group of man-apes, who learn how to use tools after encountering a strange black monolith. After one of the most famous jump cuts in cinema, the main plot begins.

Now we follow Dr. Heywood Floyd, who is heading for the Clavius Base, an American outpost on the moon. Upon arrival, Dr. Floyd is informed of the discovery of an artificial artifact buried in the moon four million years ago. Eighteen months later, a spaceship departs to Jupiter, from which the artifact is thought to originate.

The ship carries three scientists on cryogenic hibernation and pilots Dr. David Bowman and Dr. Frank Poole, but almost every system is controlled automatically by HAL 9000, a computer with artificial intelligence believed to be incapable of error. The blind trust in HAL’s capabilities, however, proves to be a big mistake.

1. Stalker

Andrei Tarkovsky’s last film produced in the Soviet Union may feel slow and boring to an audience used to Hollywood productions. Nonetheless, to those able to navigate through its complex dialogues and symbology, watching this masterpiece can be a life-changing experience.

In the indefinite future, a man known as the Stalker works as a guide to a place called the Zone, a region full of traps and debris that appears to be sentient. Inside the Zone, there is the “Room”, which is said to grant the innermost wishes of anyone who steps inside.

For this reason, the region is blockaded by the military, as someone ill-intended might use it to bring all sorts of evil to the world. The film follows the journey of three men: the stalker, the writer, and the professor, as they travel through the Zone while questioning each other’s motives and worldviews.

The fact that none of the characters have a proper name is crucial to understanding Tarkovsky’s intentions. This is not supposed to be a film about the journey of those men; it is a film about their ideas. Each character is an archetype of a certain way of thinking, whereas the Zone itself can be seen as a metaphor for God.

The stalker, able to navigate through the Zone’s invisible trails, represents faith. The writer, with his acid comments and pessimistic take on life, represents art, and as such, is mired with dilemmas over his own utility and place in the world.

The professor represents empirical science, more focused in observing the zone than making any statements. To them, the journey to the Room is a mixture of expedition and pilgrimage. Thus, “Stalker” is a great example of visual media being used as a way of conveying ideas that would otherwise require an entire book.

Author Bio: Henrique Fanini Leite is an engineer, currently working for the Brazilian Space Program. He started writing professionally during university. Since then, he has published a book and short stories on-line, in anthologies and magazines.