The long-running horror franchise is the most loathed of all cinematic forms. Bad sequels poison our memories of earlier films and mishandled properties kill off what we have loved about the originals. But buried within these forgotten and neglected films there can also be greatness.

Extensive franchises often provide diminishing returns in quality, but they also remind us that we are watching a commercial product, an industrially manufactured piece of entertainment full of properties that need to be used and studio time that needs to be filled.

Auteur theory puts forward an idea of films as singular works of art controlled by their director, but the late franchise is the opposite of this. These films swap out actors, writers or directors and no-one is connected to the film in any meaningful way. They exist in relation to whatever parts come before and after.

Horror films make particularly good franchises because they are built on simple and effective ideas that can be replicated. But the need to continue a series when those ideas have run out, or there is little creative incentive, can be an interesting motivation. Franchise entries beyond trilogies have to look for increasingly radical and inventive ways to keep audiences entertained.

If these films remind us of their commercial nature then they need to actually make money; it isn’t enough just to have Freddy Krueger kill a few more teenagers. Similarly, these late sequels are often distributed outside of the standard exhibition model. That could mean short theatrical runs, straight to video or DVD or through video-on-demand services.

This approach takes the pressure off franchises, giving them the freedom to experiment and hire untested directors. Some directors on this list even had the opportunity to make daring and personal films that were funded and distributed hidden beneath a long-running series.

1. Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter (Joseph Zito, 1984) (4)

There comes a stage in every franchise’s lifespan when they have to imply some bold change has taken place to breathe new interest in a series. Informally five seems to be the limit at which numbers can still be used in a title and then comes the refreshed subtitle, The Rebirth, Regeneration, Resurrection and so on. For the Friday the 13th series that entry comes at five with Friday the 13th: A New Beginning.

But the film that precedes this, Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter, is an unusual high point for the franchise that is actually diminished by the supposed new beginning. The setup for the film is shockingly unoriginal, even in the world of franchises, but the simple foundation allows for excitement and innovation within that basic framework.

Jason Voorhees wakes from Part III’s supposedly mortal wound and returns to Crystal Lake to continue killing teenagers. That is the entirety of the narrative. What makes the film so engaging is a combination of a likeable and witty cast and a particularly callous approach to killing them off, courtesy of effects icon Tom Savini.

Corey Feldman and Crispin Glover give the perfect eccentric performances that would define their later careers, but the rest of the large cast is also great. The entire films has an ensemble quality, full of long enjoyable group scenes, that makes the deaths sadder and more effective.

The effects are brutally static with few cut-aways, and Savini focuses particularly on blades though necks and hands and people being thrown through windows. In fact so many hands are mangled (including Jason’s) it’s hard not to read it as some sort of theme. The visual inventiveness of some of these sequences is so elaborate they could almost be funny, if they weren’t quite so grisly.

2. Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning (John Hyams, 2012) (6)

The Universal Soldier franchise is interesting because it wasn’t actually very strong to begin with. The first 1992 film is a lumbering Jean Claude Van Damme vehicle that plays to the strengths of neither the hero or director Roland Emmerich. The canon is also extremely confused, with six films, two made for television and two for video on demand, and multiple subtitles, like The Return, Regeneration, Unfinished Business etc.

In 2009 John Hyams, the son of director Peter Hyams, relaunched the franchise with Universal Soldier: Regeneration. Hyams trained as an artist and developed experience with television and documentaries, but was untested as a director of large-scale franchise properties. He might have been interested in the franchise because of his father’s relationship with Van Damme (they made three films together) and because any commercial or critical following for the films was basically non-existent.

Regeneration is interesting, but its modest success and unusual marketing (it only received theatrical exhibition in the Middle East and South-East Asia) let Hyams direct and edit its incredible sequel, Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning.

Here the director transforms an indistinct franchise into a lean and extreme exercise in action and horror, whilst treating the original films with affection. Without the restraints of cinema releasing the violence can be both graphic and fantastical. The fights between the enhanced soldiers are ultra-refined and dragged out, until the action film becomes body horror as they push far beyond the limits of the human form.

Striking long takes, clear editing and a toxic sense of unease and fear about the self and the body turn the franchise into something unique and powerful. The film pushes the figures of the previous films to the margins and creates a story of conspiracy and alienation that recalls 1970s films from Alan J. Pakula and indeed Peter Hyams’ Star Chamber and Capricorn One.

Van Damme and Dolph Lundgren become Kurtz-like figures, pursued through a mind-altering world of steroid psychedelia and mind-control.

3. A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (Chuck Russell, 1987)

For the third A Nightmare on Elm Street film Wes Craven, Frank Darabont, Bruce Wagner and the director completely rethought the franchise. They chose a young ensemble cast and developed the idea of a group of teenagers dealing with the aftermath of Freddy Krueger in a mental hospital. After a string of disturbing deaths the group use their dream powers to battle the monster.

The fantastic Heather Langenkamp returns and Angelo Badalamenti’s score is wonderfully evocative, exploring the dream-like territory he would bring to Twin Peaks three years later.

The tone of this film is also altered to incorporate a fantasy element, and these surrealist dream sequences are consistently astonishing. Krueger comes out of televisions, he becomes a giant worm, transforms into a beautiful woman and, in a sequence which led to the film being banned in Australia, his fingers are replaced with syringes.

The film is dark, funny and terrifying at the same time and it helped launch the careers of Laurence Fishburne and Patricia Arquette. There isn’t much more you could ask for in a late franchise sequel; it’s respectful of everything which makes the original so iconic, but adds new ideas and approaches, whilst using the tragic ending to set up the fourth instalment.

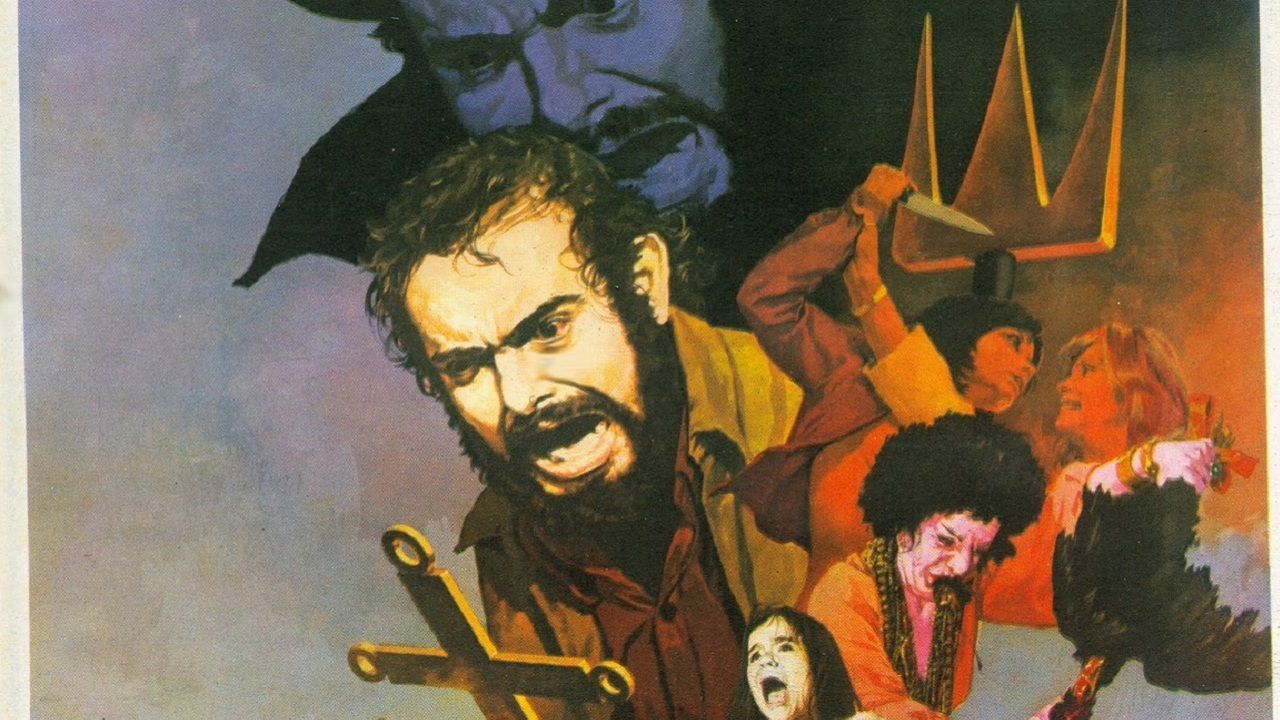

4. The Bloody Exorcism of Coffin Joe (José Mojica Marins, 1974) (6)

Of all the franchises on this list, José Mojica Marin’s Coffin Joe series is the weirdest, both in content and execution. The films are baffling and extreme experiments in exploitation violence, sex and style. They are also unique because Marins directed all eleven of them, from 1963’s At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul, to 2008’s Embodiment of Evil. He managed to do this with minimal funding and contemporary interest, single-mindedly pursuing these bizarre tales of a masochistic figure searching for his true love.

Although there is some debate as to which films constitute the official Coffin Joe Trilogy, each of these films use the character of Joe and have Marins’ distinctive blend of psychedelia, cheap effects and twisted imagination. But what is uniquely fascinating about The Bloody Exorcism of Coffin Joe is how it pre-dates what would become a common franchise technique in the 1990s; the meta-franchise.

The most well-known example of this is Wes Craven’s New Nightmare. This meta film focuses on the production of a new A Nightmare on Elm Street movie and within that film Freddy Krueger is a fictional construction, who begins to develop a life of his own within the fictional production.

The films addresses ideas of why we enjoying watching horror and the process of making disturbing or gory films. When you have extinguished all potential outlets for your characters, this meta-textual reworking of the material is a novel and easy to produce idea. It is also an idea that Marins embraced twenty years before Wes Craven.

The Bloody Exorcism of Coffin Joe is about Marins completing production on a Coffin Joe film. When interviewed in the film he states that Joe is an entirely fictional character, but of course that is not true. What follows is a stream of torture and mutilation with Marins starring as both Joe and the timid director José Mojica Marins. It is an extremely bizarre franchise film that predicts the state of the modern franchise by replacing new ideas with narrative trickery.

5. Halloween 3: Season of the Witch (Tommy Lee Wallace, 1982)

With Halloween 3: Season of the Witch Universal Pictures discovered a bold new way to regenerate a franchise without a new subtitle or repetition; they simply removed every trace of the franchise from the film.

The third entry in the Halloween saga is loathed by fans because it does not feature Michael Myers and it not connected with the previous films in any way. What is does feature is a soundtrack and production duties from John Carpenter, after he skipped Halloween II, and a script produced by Carpenter and his long-time icon British sci-fi veteran Nigel Kneale.

Unfortunately Kneale hated the additional violence and gore that was brought to his eccentric script and had his name taken from the credits. But the utter strangeness of the narrative makes it a strong addition to an already ailing franchise.

An evil corporation plans to use masks containing elements from Stonehenge to sacrifice the wearers to the old gods and usher a new age of witchcraft. There are also some androids and something about the masks controlling snakes. The whole project is a bitter attack on television and the commodification of the occult from a cynical screenwriter unhappy with being reduced to working on corporate franchises.

For all the late sequels that use post-modern techniques, this film contains the most cynical observations on originality and mindless consumption.