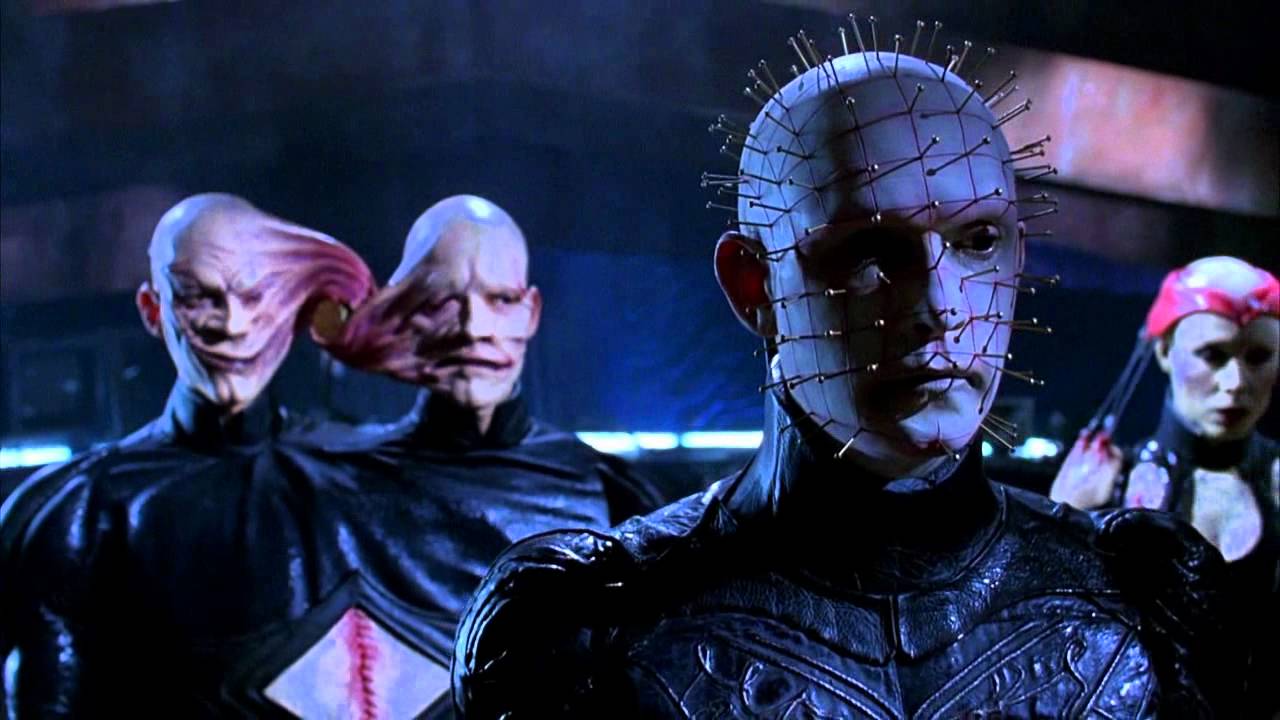

6. Hellraiser IV: Bloodline (Kevin Yagher, Joe Chappelle, 1996)

The Hellraiser franchise is now on its ninth iteration and a remake (the solution to any failing franchise) has been in development purgatory since 2006.

The most recent entry in the series, Hellraiser Revelations, was made solely so Dimension Films could retain its rights to Clive Barker’s material, it was shot over eleven days, cost an estimated 350,000 and was released in a single cinema before disappearing onto DVD. This is arguably the purest franchise of all, the films continue to be made, but no-one is watching. But this sad end to Barker’s fantastic sadomasochistic series did not seem inevitable in 1996 when Hellraiser IV: Bloodline appeared.

Despite a troubled production that ended in two directors disowning it and four potential final cuts, the film has plenty of ideas and a reasonable production budget. The last entry that Barker was involved with, the film takes place in 1796, as a French toymaker produces the dreaded Lamont Configuration, in 1996, as the toymaker’s ancestor uses blueprints for the device in his architecture and in 2127 as his ancestor opens the box on an orbiting space station.

Although the CGI effects in the final sequence probably looked dated by 1997 the new Cenobites are suitably disgusting and the narrative is both committed to the ideas of the original, but also ambitious in its scope. The ideas of the film aren’t matched by the technical skills of those involved, but this doesn’t deserve the fate of the most recent entry.

7. Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (Terence Fisher, 1974) (7)

As the seventh instalment of one of the most franchised of franchises and produced in the middle of Hammer Pictures’ financial and creative decline, Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell does not deserve to be as incredible as it it.

This taut chamber piece is the final film Terence Fisher directed for Hammer and at this stage in his career he had developed a clear and controlled style, perfect for Hammer’s production line structure. Between 1948 and 1969, with the exception of 1961, he had directed at least one film a year, but often directed as many as four. So, it is no surprise he had refined a fast and effective process, with plenty of visual inventiveness.

The same is true of Peter Cushing, who reprises the role of Baron Frankenstein for the last time. Every single gesture and tic has been perfected, creating space for nuance and subtlety. The Baron’s steely confidence is always present, but there is a hint of melancholy as he recalls a career of setback and failure.

After a young scientist is imprisoned in a gothic asylum for attempting to replicate Frankenstein’s work, he discovers an aged Baron working within its walls. The bars on every window frame the pair’s experiments with reanimating the dead and the issue of mental health in the asylum is handled with relative sensitivity.

The cheap effects for the monster create a grotesque impression and the the ending is resolutely brutal and bleak; the dead are cleaned away and the Baron returns to his neverending work. That no attempt at resolution was made despite the ages of director and star becomes a celebration of the franchise; he will keep working again and again, tirelessly reproducing his youthful glories.

8. Return of the Living Dead III (Brian Yuzna, 1993)

With Return of the Living Dead III, Brian Yuzna uses this established counter-franchise to launch an extremely personal project that smuggles in ideas of self-loathing and suicide. Two years after his landmark splatter horror Society he took over direction for the Return of the Living Dead franchise, an alternate offshoot from George Romero’s original film. His Return of the Living Dead III recalls Society’s blunt socio-political criticisms as well as its industry-peak practical effects and cynical perspective.

But this cheap and nasty franchise revision quickly becomes a baffling doomed romance amid the dank convenience stores and locales of Los Angeles. Dropping the wit and self-reflexive humour of this branch of the franchise, Yuzna instead opts for a harrowing story of self-mutilation and loneliness.

When a wannabe grunge drummer and his girlfriend sneak onto a military base they witness a chemical being used to reanimate the dead. So, inevitably when Curt crashes his motorcycle, killing Julie just as they begin their new life together in Seattle, the facility is where he heads.

Surprisingly Julie’s death is sensitively handled and affecting. Once reanimated her consciousness is intact, but she obviously craves human flesh. After a run in with a local gang, and some brain eating, she discovers pain offers a distraction from her compulsions. Mindy Clarke is wonderful and her switches between ravenous violence, and self-loathing are very.

After a moving failed suicide from L.A.’s 7th Street Bridge the pair descend first into a viaduct and then Los Angeles’ sewer system, assisted by an enigmatic homeless man and pursued by the gang they injured earlier. The finale is suitably gory, but it’s also an effective study of compulsion and love.

Despite themes of self-harm and unwanted thoughts there is still plenty of fleshy effects work for Steve Johnson; spines are stretched and reanimated, heads are are removed and there are some disturbing body modification images that pre-date extreme Japanese horror such as Tetsuo or Takeshi Miike’s work.

9. Howling VI: The Freaks (Hope Perello, 1991)

The original The Howling was a very effective werewolf horror with excellent effects, a satirical script from John Sayles and lovely, visually exciting direction from a young Joe Dante. But this affectionately old-fashioned genre film was never intended to launch a franchise.

This was a carefully crafted, one-off B movie, complete with Roger Corman cameo. But unexpectedly the film was a massive success, fuelled by a strange obsession with werewolf films in 1981, which also saw the release of Wolfen and An American Werewolf in London. So begins one of the most unloved of horror franchises, a franchise that lasts until 2011’s The Howling: Reborn and has arguably the most substantial drop in quality of any of these series.

It’s hard to identify why this sixth film has particular merit. None of the four films in between have any notable significance, no cast or director returns from the original, the film went direct-to-video and it doesn’t connect with the rest of the franchise in any way.

Perhaps it is the complete absence of any expectations from the distributor and fans, if there even were any, that creates a strange freedom. The director Hope Perello had worked as producer for the original Puppet Master and as production crew on a number of great genre films, many connected with Re-Animator’s Stuart Gordon Green, including From Beyond, Robot Jox and Dolls.

This means the production is flawless and surreal. The visiting freakshow is a baffling collection of terrifying oddities. Although this is Perello’s directorial debut she is more than competent, using lovely tracking shots to slowly develop the strong script and excellent performances from Bruce Payne as R.B. Harker and Brendan Hughes as Ian.

Considering how long the franchise had been running, it is strange that the film crams in so many ideas (ideas that could reasonably have been used in other entries); a sympathetic werewolf, vampires and a travelling circus referencing Tod Browning’s Freaks. The final result is a genuine anomaly in the franchise, a strangely quiet and sensitive film full of emotional dialogue and subtlety.

10. The Puppetmaster 3: Toulon’s Revenge (David DeCoteau, 1991)

Most of the franchises on this list became franchises because they began as exceptionally strong critical and commercial successes. But the first Puppet Master film does not even fulfil these requirements, not having received any theatrical release. Producer Charles Band realised he could make more money with a straight to video production, and this mentality defines the entire nine film series.

But, once a film is disconnected from the cinema industry, and the reviews and critics of that circuit, it has to compete in the whole new arena of word-of-mouth video. This goes some way to describe the utterly bizarre Nazi-puppet-period prequel Puppet Master III: Toulon’s Revenge.

What is most significant about this film is the towering central performance from Guy Rolfe, the eighty-year old English thespian who gives a tragic performance as the tortured puppeteer Andre Toulon. The puppets are gorgeous and the stop motion animation is great, unfortunately the rest of the film is rather cheap in comparison.

Toulon uses a serum to bring his puppets to life and create a satirical puppet show, but the Third Reich quickly tries to enlist the marionettes in the war effort. After his wife is murdered, the mild-mannered Toulon seeks revenge on everyone involved in the reanimation project. The film’s highlight is when the dolls begin to maim, shoot and attack the humans in a range of blackly hilarious visual sequences. The film is also an example of another modern franchise ploy; the prequel.

Aside from Rolfe’s performance, the complete disregard of spatial logic and narrative sense make this film a charming entry in an otherwise unredeemable series. It’s also pleasing to see David DeCoteau as director. DeCoteau worked under B-movie maestro Roger Corman, and, unlike many of the master’s proteges, is completely committed to making genre films with shoestring budgets and titles like Shrieker and The Frightening.

Author Bio: Chris Trowell is an editor and film critic based in London. He claims to love everything from silent cinema to Taiwanese New Wave, but mostly just watches 1980s slasher films. You can follow him on Twitter.