The new millennium has graced us with some phenomenal films from many talented directors. Many of those directors, whether previously in front of the camera or limited to screenplay writing, took the reigns behind the camera for the first time. Below is a discussion of fifteen of the best such directorial debuts.

Of course, the passing of the twentieth century and the marking of the twenty-first for these reviews is merely arbitrary, as there were many such debuts that would certainly be worth mentioning, but for the fact that they were made prior to 2000 (e.g., Pi [1998, Darren Aronofsky]).

Of the hundreds of films done after 2000, many could also be included in this list. The list below includes films whose first-time directors have quite diverse backgrounds. No attempt is made to cover every year. Because the subject is directorial debuts, a bit of extra time is spent on the directors themselves.

15. George Washington (2000)

Director David Gordon Green entered the director’s chair, showcasing the new millennium with his film, George Washington. Green’s films, which are usually coming-of-age tales set in small rural towns, have been categorized as belonging to the Southern Gothic tradition. Green’s dialog often has an obtuse, semi-poetic quality.

While in university, he made the two short films, Pleasant Grove and Physical Pinball, at the North Carolina School of the Arts prior to his feature film debut in 2000, the critically acclaimed George Washington, which he both wrote and directed. He followed that in 2003 with All the Real Girls and Undertow in 2004. In 2007, he directed Snow Angels, his first film of another author’s screenplay, adapted from the Stewart O’Nan novel. Since 2008, he has also transitioned into comedy, directing the films Pineapple Express and Your Highness.

His film George Washington is about black and white kids whiling away a long, hot summer in North Carolina – almost floating in torpor – a torpor which is dispelled by the tragic accident they finally get mixed up in. It is superbly photographed and its tremendous compositional sense shows the rigor of a young master.

The railroad tracks, clapboard houses and municipal swimming pool endow the movie with a distinctively classic, almost literary feel; it gestures to a robustly American cultural context which seems to go back to the novels of William Faulkner and Mark Twain.

This is also a movie which shows poor white and young black people without aggression, without cynicism, without attitude, without Tupac or Eminem on the soundtrack. They exist in a cinematic space innocent of any of this, and yet the movie never for a second looks naive or dated.

And the performances from the non- professionals that Green has recruited are simply miraculous in their easy charm. George Washington is an almost awe-inspiringly accomplished movie with an absolute faith in its own aesthetic sense, and an unapologetic preoccupation with finding beauty in the look of ordinary places, people and things.

Yet it is as much concerned with this uncomfortable transition as it is with a Deep South overrun by poverty and the falseness of racial interaction. Green’s portrait of the South, though, is anything but hostile. Utopian without the naivete, George Washington posits the possibility of a racially harmonious South.

14. House of Sand and Fog (2003)

This film is an American drama directed by Vadim Perelman. The screenplay by Perelman and Shawn Lawrence Otto is based on the novel of the same name by Andre Dubus III. Vadim Perelman made his directorial debut with this film following a successful career as a commercial director. The film was nominated for three Academy Awards, Best Actor (Ben Kingsley), Best Supporting Actress (Shohreh Aghdashloo) and Best Original Score (James Horner). The film also marks Perelman’s first screenplay credit.

In the film, Massoud Amir Behrani is living a lie to fulfill a dream. Once a member of the Shah of Iran’s elite inner circle, he has brought his family to America to build a new life. Despite a pretense of continued affluence, he is barely making ends meet until he sees his opportunity in the auction of a house being sold for back taxes. It is a terrible mistake. Through a bureaucratic snafu, the house had been improperly seized from its rightful owner, Kathy Lazaro, a self-destructive alcoholic.

The loss of her home tears away Kathy’s last hope of a stable life–a life that had been nearly destroyed by addiction–and Kathy decides to fight to recover her home at any cost. Her struggle is joined by deputy sheriff Lester Burdon, who tries to take the law into his own hands to help Kathy. Ultimately the tale, itself, explores what happens when the American Dream goes terribly awry.

The performance of such a heavyweight like Kinsley is indeed well adorned by that of Aghdashloo, yet these two seem to overpower Jennifer Connelly nearly to the point of overkill.

The film no doubt took on a different resonance after 2008 after the collapse of the housing market led to record numbers of foreclosures across the country (even though the house in the film was not lost to foreclosure, but to an alleged failure to pay real estate taxes by the previous owner). Most of the foreclosed houses were purchased by the very same banks who mortgaged them in the first place.

These houses were then sold at auction for pennies on the dollar. So disastrous was the crisis that a new cottage industry arose with real estate investors snatching the distressed properties like vultures, only to flip the properties to new homeowners within very short order. Interestingly, Perelman stated that what drew him to the story was his own immigrant experience, and that this experience greatly informs the film.

Watching the film after 2008, however, seems to put in stark relief the near irrelevance of the conflict between Kathy and Behrani. Every stage of its escalation seems determined less by the psychology of the characters than by the forced, schematic logic of the story. The logic of sheriff Burdon’s leaving his family and love interest in Kathy is less understood as it is woefully undeveloped and indeed seems loosely attached with duck tape to the main plot.

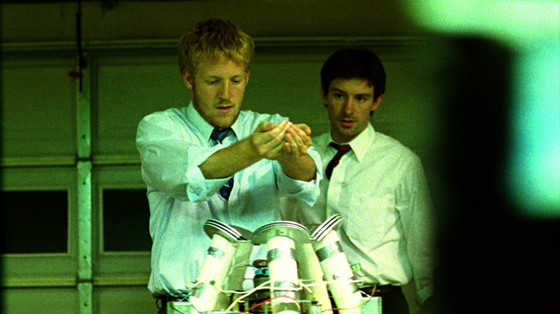

13. Primer (2004)

Math wiz-turned-director Shane Carruth directed this American indie science fiction drama film about the accidental discovery of a means of time travel. The film, shot on 16-millimeter for a budget of around $7,000, is an ingenious movie about the perils of ingenuity. Two would-be inventors, Abe and Aaron, working after hours in their suburban garage, stumble onto an invention whose application is not obvious at first but whose ethical and metaphysical implications quickly become enormous.

Abe (David Sullivan) describes it to Aaron as “the most important thing that any living organism has ever witnessed,” which may be a slight exaggeration. To call the gizmo a time machine, which it more or less is, would be to create a slightly misleading impression, evoking splashy Hollywood confections like the Terminator and Back to the Future franchises, which Primer does not resemble in the least.

The film opens with four techheads addressing envelopes to possible investors; they seek venture capital for a machine they’re building in the garage. They’re not entirely sure what the machine does, although it certainly does something. Their dialogue is halfway between shop talk and one of those articles in Wired magazine that you never finish.

There’s a fascination in the way they talk with each other, quickly, softly, excitedly. It’s better, actually, that we don’t understand everything they say, because that makes us feel more like eavesdroppers and less like the passive audience for predigested dialogue. Challenging us to listen closely, to half-understand what they half-understand, is one of the ways the film sucks us in. Punctuated into the science-speak are occasional one-liners said without any sense of comedy that wake us up.

At one point, after having already engaged in several temporal journeys, Aaron blithely asks Abe, “Man, are you hungry? I haven’t eaten since later this afternoon.” The line would be lost were it not for its (unintended) comedic nature combined with the effect it has on the listener’s mind.

The film is, technically speaking, science fiction, but of an unusually rigorous and unassuming kind. Carruth, a math major in college who worked as an engineer before teaching himself filmmaking, has an impressive feel for the odd, quiet rhythms of small-scale research and development. His script captures the way these young scientists express themselves and takes note of how their intimate, competitive collaboration works in fits and starts and sideways leaps.

“They were meticulous; they were intelligent,” an opening voice-over says, and Carruth, exhibiting both qualities, assumes that the audience shares them enough to keep up with the intricacies of his narrative and with the logical permutations of his premise. This is a lot to ask — the storytelling is oblique, at times to the point of vagueness — but the effort is invigorating. Like Pi or Memento (speculative brain teasers to which this has an obvious kinship), Primer is the kind of movie likely to inspire both imitators and cultists.

At a certain point, Carruth’s fondness for complexity and indirection crosses the line between ambiguity and opacity, but Carruth has the skill, the guile and the seriousness to turn a creaky philosophical gimmick into a dense and troubling moral puzzle.

Primer is likely to turn viewers into versions of Abe and Aaron: it makes you want to sit down and draw charts and propose equations. Whether these will add up to anything more than a cerebral diversion is hard to say. Carruth invented something fascinating — a way of capturing, on film, some of the pleasure and peril of scientific inquiry — and you don’t need a time machine to predict that as he goes on, he will discover exciting new ways to put it to use.

Carruth also produced, edited and scored the film and also started in the main role as Abe. The film was honored at the 2004 Sundance Film Festival with the Grand Jury Prize and the Alfred P. Sloan Award. Carruth’s second film, Upstream Color, was released in 2013.

12. 13 Tzameti (2005)

The terrible game of life is boiled down to its essentials in this new film from 26-year-old Georgian director Gela Babluani, who makes a stunning debut with what might yet become a classic. 13 Tzameti is a story about gambling, about the tyranny of luck, the shortness of life and about the most insidious form of envy: the envy of the old for the young.

It may be said that this young director is nourished by a pessimistic vision of the world and by the search for a cinematic style with powerful images. Babluani was born in Tbilisi, in the former Soviet Republic of Georgia.

The son of prominent director Temur Babluani, Gela Babluani was sent with his three siblings at the age of seventeen to study in France. This means he lived through his formative years in the former Soviet republic, since an independent country, but that has seen several civil wars. A country whose people knew only totalitarianism under Soviet rule, then interminable internecine warfare, then suddently foisted into an absolute freedom that no one understood.

Having been raised in a world of gunfire, daily violence and death, Babluani developed a dark image of humankind, noting humans’ complexity because of their degenerate sides. He expresses the tension humans face as worlds are turned upside down as they deal with changes from innocence to nightmare.

The film also marks the acting debut of his younger brother Georges Babluani, who plays the film’s protagonist Sébastien. The film tells the story of a destitute immigrant worker who steals an envelope containing instructions for a mysterious job that could pay out a fortune. Following the instructions, the young man unwittingly becomes trapped in a dark and dangerous situation.

The action begins calmly, even torpidly, before fate lands its horrible blow, disguised as an opportunity. Sebastien is a Georgian immigrant builder in France, repairing the roof of a shabby house inhabited by Godon (Philippe Passon), a malevolent morphine addict. Godon dies unexpectedly before settling up with Sebastien, who on an angry and vengeful whim steals a letter belonging to his late employer, containing a hotel reservation, a rail ticket and instructions that appear to offer the chance of riches.

Galvanised with excitement, Sebastien impersonates Godon, unaware that he is getting mixed up in someone else’s Faustian bargain. He is taken to a remote country house where he must take part in a horrific gambling conspiracy of jaded high-rollers in which the stakes are life or death.

The film won the World Cinema Jury Prize for a Dramatic motion picture at the Sundance Film Festival. In 2006 Babluani directed a film L’Héritage with his father about several people from France who visit Tbilisi. He recently completed an American version of 13 Tzameti titled simply 13.

11. Man Push Cart (2005)

The end of the Cold War and the new millennium brought forth a veritable flood of literature in the social sciences and in fiction that has often been put (if inconveniently) under the umbrella of “post-colonial literature”. By stripping the ideological blinders that reduced observations of the human condition to the false “East-West” binary these authors provided a far more multifaceted, indeed, nearly infinite, blend of perspectives.

Among the many sub-themes were those that centered around the Faustian bargain struck by immigrants to Western countries, to wit, the “promise” of freedom (political, social, economic), in exchange for the giving up nearly every facet of one’s culture. Jhumpa Lahiri did this brilliantly in 1999 with Interpreter of Maladies (winning a Pulitzer) and Arundhati Roy did as well a decade later with God of Small Things (winning the Booker Prize).

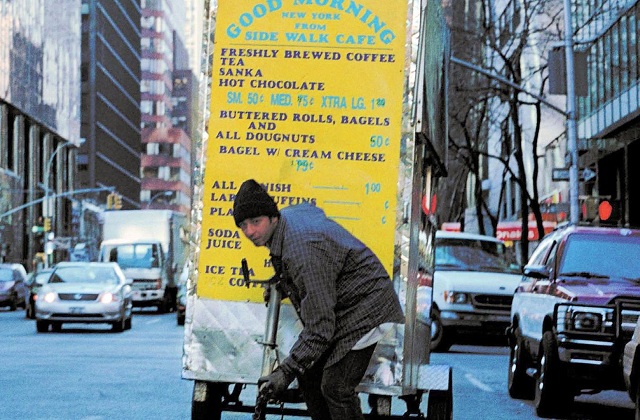

In his directorial debut, Man Push Cart, Ramin Bahrani shows how this Faustian bargain can have tragic consequences. The film tells the story of a former Pakistani rock star who sells coffee and bagels from his pushcart on the streets of Manhattan. The film premiered at the Venice Film Festival (2005) and screened at the Sundance Film Festival (2006). The film won over 10 international prizes, was released theatrically around the world, and was nominated for three Independent Spirit Awards.

This being the first of what has since become five feature-length films (Chop Shop (2007), Goodbye Solo (2008), At Any Price (2013), and 99 Homes (2015)), Bahrani clearly demonstrates his dissatisfaction with film studios’ reluctance to commit to character-driven dramas with a social conscience (like New Hollywood staple Network, for instance), instead favoring CGI-driven sure things.

In the film, we witness Ahmad (Ahmad Razvi), as he goes through a Sisyphean daily grind. In the very early hours of each morning, he commutes by subway from his shabby one-room apartment in Brooklyn to Midtown Manhattan, where he sells coffee, doughnuts and bagels on the street. Lugging his portable propane tank, he stocks his stainless-steel cart, then pushes it through traffic to his station on a corner of Avenue of the Americas.

Much of the movie takes place before sunrise during the winter months, and images of the illuminated spire of the Chrysler Building spearing the night sky and of tree branches crusted with tiny white lights evoke the city’s crushing indifference. In the scenes filmed in daylight, it is often raining.

It makes Mr. Bahrani’s small, bleak film no less gripping to know that it was, in fact, partly inspired by The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus’s treatise on the absurdity of existence. Indeed, the movie embodies the very soul of Italian neo-realism, free of contrived melodrama and phony suspense.

The movie sparingly dishes out the details of Ahmad’s life, leaving many questions unanswered. We learn that his wife died a year earlier (there is a brief, awkward flashback to happier days) but not how she died. Because Ahmad can’t afford a large enough place, his six-year-old son (Hassan Razvi) is living with his in-laws. Ahmad’s angry mother-in-law (Razia Mujahid) blames him for her daughter’s death and tries to keep his son from him.

We also learn that Ahmad was a Pakistani rock star who had a hit record in 1995. Exactly when and how he came to the United States is never specified. He now sells bootleg pornographic DVD’s as a sideline, for $8 apiece or two for $15. (The movie quickly lures you into its desperate nickel-and-dime mind-set.)

Filmed in less than three weeks, Man Push Cart is an exemplary work of independent filmmaking carried out on a shoestring. Mr. Razvi’s convincing performance is a muted portrait of desolation in his adopted country bordering on unending despair.