8. La Haine

The defining “banlieue” movie, La Haine (which means “hate”) shows a restricted time in the life of three young men of suburban Paris; their relationship with violence and society comes to a dramatic climax during the 19 hours depicted in the film.

After a riot, Vincent Cassel’s character Vinz finds a gun which obsesses him as a potential tool of vengeance against society and policemen in particular. More in general, the film is an accomplished attempt at a realistic and gritty style which depicts everyday suburban life, in its rare and simple pleasures as well in its many frustrations.

La Haine is an unapologetic and compelling modern tale of social distress, and its description of the Parisian banlieues is perfectly apt for the contemporary social discussion about city suburbs and how to survive them.

7. L’Atalante

L’Atalante is the only full-length feature by Jean Vigo, who died of tuberculosis in 1934 shortly after the first cut of the film.

The protagonist are Jean, a barge captain, and Juliette, the young woman he marries; together, they sail until they get to Paris, a city whose allure and temptations make Juliette escape from the barge after an argument with Jean whothen starts longing for his beloved.

The story is a not particularly original love story with an obligatory happy ending, but L’Atalante is recognized by critics as a filmmaking masterpiece and, despite being a commercial and critical failure at the time of release, after World War II it gained a cult status. Among the directors who admired and homaged the film there are Bernardo Bertolucci, Luigi Comencini and François Truffaut.

The film is notable for his deviation from completely realistic storytelling: L’Atalante is one of the earliest examples of the poetic kind of cinema France often offers to the world, as some of the other films on this list prove. This non-realistic approach reaches its height in the famous and almost surrealistic underwater scene, when Jean sees a vision of his beloved wife laughing.

6. Playtime

In 1953 Jacques Tati, a former stage performer and actor turned director after World War II, debuted the character Monsieur Hulot with Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot. Hulot, who returned 5 years later in Mon Oncle, was a comedic persona similar to the one Buster Keaton played in many of his films; Tati made him a quiet observer of the society around him, and while the first two films that starred the character were straight-forward, character-driven comedies, he decided to create a more ambitious oeuvre with the third one, Playtime (1967).

The film was produced over many years and in 70mm; it made use of a gigantic set which depicted a sort of futuristic Paris full of modern but sterile spaces. The Paris we see in Playtime is full of glass and steel, a pessimistic image of what Tati felt were the changes the city was heading into during those years.

Unsuccessful after its release, Playtime is now one of the most studied movies of cinema history due to its innovations and visionary style. It’s easy to watch the work of certain modern directors, for example Wes Anderson, and recognize the influence of this 1967 French masterpiece.

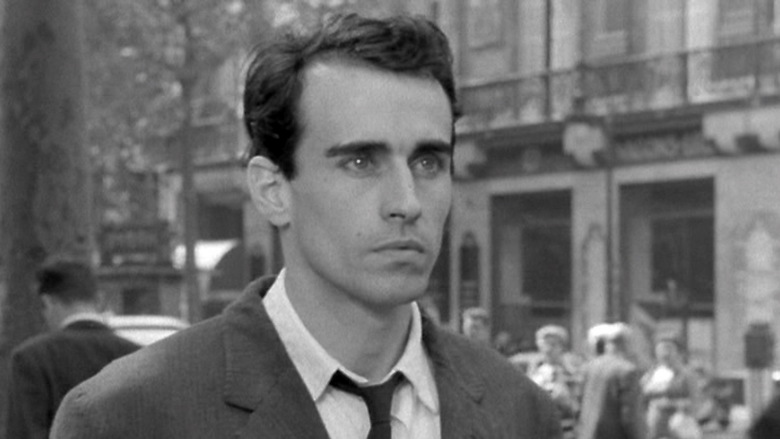

5. Pickpocket

Robert Bresson was once described by director Alain Cavalier as “the father of French cinema” (the mother being Jean Renoir) and his influence was fundamental, but never restricted to, the Nouvelle Vague; his 1959 film Pickpocket is one of his best known works. The film is a perfect match of pure style and story. Its rhythm is flawless; there is a large use of voice-over and very original editing and camera movement techniques which recreate the persistent state of suspense the protagonist is in.

Pickpocket is considered by many a nearly perfect film, and has a large following among filmmakers. A vocal fan of Pickpocket is legendary screenwriter Paul Schrader, whose work often reflected the atmosphere of the film; this is also true regarding his script for Taxi Driver, directed by Martin Scorsese, who often took inspiration himself from French cinema of the 1950/60’s.

4. Ascenseur pour l’échafaud

Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (Elevator to the Gallows) is the first film Louis Malle directed after winning the Palme d’Or with the documentary Le Monde du Silence. The film mostly takes part during a single night during which we follow various characters, all linked to the crime perpetrated by Julien Tavernier, a former soldier whose elaborate plan to kill his boss and escape with the wife’s boss, his lover, doesn’t completely work.

Tavernier gets stuck in the office’s elevator, and consequently his lover starts to think he betrayed her and has escaped; the character of the wife’s boss is portrayed by Jeanne Moreau, who gave one of the best performances French cinema had yet seen. Her lonely and desperate night walk through the streets of Paris carries an incredible amount of sentiment and anguish.

The film is known for anticipating many stylistic choices of the Nouvelle Vague, but it stands on his own due to its unique traits. The score was improvised by Miles Davis himself while he was watching footage of the movie; the photography of Henri Decaë consists of a beautiful black and white whose contrasts are particularly heightened. As time passes, Ascender pour l’échafaud’s style becomes more and more admirable and one can easily call the film a pivotal turning point for modern cinema.

3. Les Enfants du Paradis

Les Enfants du Paradis was released in 1945 and was shot by Marcel Carné while Paris was still occupied by the Nazi army. The film was written by poet Jacques Prévert and consists of two parts, one set in 1827 and one seven years later; it revolves around the the boulevard du Temple (often called “boulevarde of crime”) where The Théâtre des Funambules is located.

This is the place where four men court Garance, an hypnotically fascinating woman played by Arletty, a frequent collaborator of Carné who also modeled for the likes of Braque and Matisse. The film is filled with a poetic quality which makes it the most unforgettable French movie of the 1940’s and also the perfect example of “French touch” applied to a classic film genre: it is not casual that Les Enfants du Paradis was promoted as “France’s answer to ‘Gone to the Wind’ ”.

The film was highly appreciated at the time of release and is still now largely regarded as a true masterpiece, with its impressive sets, its mix of realism and dream-like atmosphere, and perhaps most of all its performances which (like those of many films in this list) wouldn’t have the same mesmerizing effect it they hadn’t a specific Paris background, in this case the notorious “boulevard of crime”.

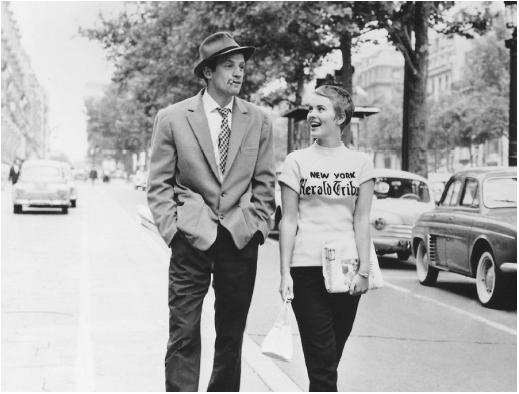

2. À Bout de Souffle

À Bout de Souffle was the breakthrough movie for Jean-Luc Godard, who came from the same milieu of Bazin, Truffaut, Resnais and many others linked to the Nouvelle Vague movement.

The film has two main undeniable qualities. Firstly, it was stylistically revolutionary for the time, employing a free-form style best represented by its use of jump cuts. Moreover, À Bout de Souffle also summarizes a whole generation’s world view, or at least its attitude towards a fast-changing world. An example is the growing dependence on American iconology and lifestyle, here represented by the protagonist’s fascination for Humphrey Bogart and by the nationality of his lover, the American Patricia.

À Bout de Souffle is one of the late 50’s/early 60’s French films which made a generation of filmgoers and filmmakers fall in love with the French artistic touch applied to cinema, and is still remembered by many as the main example of that period of cinema history.

1. Les 400 Coups

After his years as a writer for André Bazin’s magazine Cahiers du Cinéma, during which he became one of the most provocative and influential film critics of the 1950’s, in 1959 François Truffaut made his debut as a director with the highly autobiographical Les 400 Coups, the story of a troubled young man and his misadventures. The film is the most known but also the most artistically fulfilled work of a Nouvelle Vague director; its freshness and beauty are still intact today.

The title sequence of the film is set over shots of Paris which are mostly taken from low-angles (almost as from the point of view of the young protagonist), starting with the most iconic of all the symbols of Paris, the Tour Eiffel. This opening anticipates the greatest strength of the movie, which is a faithful and fascinating depiction of everyday Paris life, with its corners, its buildings and also its people.

By making us follow young Antoine, Truffaut reveals a side of Paris which at the time could actually pass as unnoticed to those who only thought of the city in its idealized, “19th century” form: Les 400 Coups has the undeniable value of making the city of lights look as lively as ever.

Author Bio: Riccardo Basso is an Italian cinephile specializing in Humanities and Philosophy. He has only recently started writing about his favorite interest, cinema, but wishes to continue doing it (just don’t tell his cinephile friends he has seen every 007 movie at least three times).