8. Bad Lieutenant (Abel Ferrara, 1992)

Widely regarded as Ferrara’s greatest film, Bad Lieutenant could be considered as a spiritual descendant of Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. Like Scorsese’s film, Bad Lieutenant focuses on a nihilistic, misfit protagonist’s attempts to find his place in a hostile, unfriendly world.

Harvey Keitel’s titular character has failed in every way a man can fail. He is a terrible husband to his wife, a corrupt police officer, sexually violent, addicted to crack and heroin, and a gambler who doesn’t know when to quit. His quest for redemption is represented both in his attempt to track down the two youths who raped a nun, and his increasingly disastrous betting on baseball games.

Over the course of the film’s ninety-six minute runtime, Ferrara shows us the gradual and absolute collapse of a human being. As he loses bet after bet that he cannot pay, his chances of escaping the violent retribution of the gangsters he owes money to diminish.

What makes his descent so heartbreaking is that even as he destroys himself, he is always looking for a way out. No matter how bleak his situation, no matter how self-destructive his behaviour, part of him is fighting to save himself, and that’s what makes the film a masterpiece.

And it could be argued that he finds his redemption after all, though of course if he does, it’s a redemption of a very strange variety. He certainly does something that helps two people in an enormous way, but the two people he helps are the very rapists that, earlier in the film, he swore to kill.

Is this the final, desperate act of a man who needs to do something good for someone in order to face his death, or is it a genuine act of kindness, a hint that there was good in the Lieutenant after all? And is there, indeed, even a difference?

7. Unforgiven (Clint Eastwood, 1992)

Sometimes, the most interesting redemption stories are those that leave it in doubt as to whether the characters have achieved redemption or not. Unforgiven is one such.

Clint Eastwood’s protagonist, William Munny, was once a thug for hire who has, in his own words, “killed most everything that walks or crawls on this Earth”. Years after retiring, he takes on one last job to kill the men who disfigured a prostitute.

Accompanied by his friend Ned (Morgan Freeman) and a young would-be hard man (Jaimz Woolvett), he sets out to track the men down, but the ghosts of his past return to haunt him.

In a way, Unforgiven is about the nature of killing. The boastful, unrepentant men in this film – those who fit the Wild West stereotype – are exposed as liars while the men who have killed are forever scarred by their actions.

Munny desperately wants to escape his past, but the necessity of violence forces him to resurrect the ghost of the man he once was.

While portraying Munny as a sympathetic character who genuinely wants to leave behind his bloody past, Eastwood’s film is also willing to ask whether or not it is truly possible for someone to change so drastically.

6. Shifty (Eran Creevy, 2009)

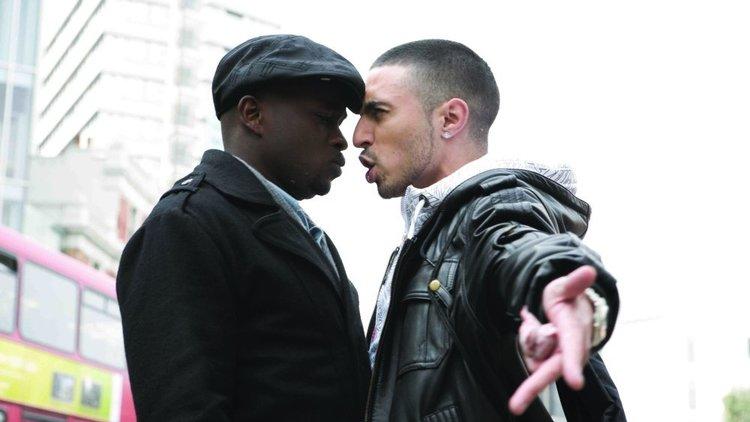

Eran Creevy’s urban thriller Shifty is about two friends, Chris (Daniel Mays) and Shifty (Riz Ahmed). Shifty is a crack dealer while Chris is an old friend of his who has left the criminal world behind and moved to Manchester.

When he returns to visit, the two become embroiled in a dispute with a rival drug dealer and attempt to repair the damage done to their friendship when Chris left town.

The film deals with the idea of escaping from the life of crime – what does it take to get out of that world and stay out, and why has Chris managed to do it while Shifty hasn’t? Shifty asks the question: is everyone capable of being redeemed?

5. Adulthood (Noel Clarke, 2008)

Noel Clarke wrote his debut film KiDULTHOOD (Menhaj Huda, 2006) after seeing Kevin Smith’s Clerks and deciding to make a film that depicted working-class British youth with the same authenticity with which Smith portrayed his characters.

Adulthood follows Sam, played by Noel Clarke, who has just been released from prison after serving a six-year sentence for the murder he committed in the previous film.

Once out of prison, Sam learns that his victim’s relatives and friends are out to kill him in revenge, and the story takes place over the course of twenty-four hours, during which he attempts to survive and protect his family.

While the high-stakes thriller plot goes on, however, the audience gets to know Sam, and we see that he has metamorphosed from the terrifying force of nature of KiDULTHOOD into a man who is conscious of the enormity of his crime, and wants more than anything else to atone for what he has done. His desire to make amends becomes every bit as important to the story as his will to survive.

4. In Bruges (Martin McDonagh, 2008)

In In Bruges, Ray (Colin Farrell) is a hitman sent to kill a priest. In the course of the murder, the inexperienced Ray kills a young boy. The rest of the film takes place in Bruges, where Ray and his fellow hitman Ken (Brendan Gleeson) have been sent by their employer to await further instructions.

Early on in the film, then, Ray feels himself to have committed an unforgivable sin, and eventually becomes suicidal as a result of his guilt.

As the events of the film take place, Bruges becomes a sort of purgatory, a place of agonising waiting, where the characters go until their fate has been decided.

The strange and often surreal events that the two protagonists experience in the film create a sense of dislocation, as if they are somewhere not of this world. The themes of judgement and responsibility run through the film, as characters meet their ends in ways that, in retrospect, seem both arbitrary and inevitable.

Harry, the two men’s boss, kills a dwarf dressed as a schoolboy while shooting at Ray. Thinking he has killed a child, he commits suicide on the spot, having said earlier in the film that that is what he would do if he ever did something so awful.

Ken, meanwhile, is initially ordered to kill Ray, but takes pity on him when he learns that Ray has become suicidally depressed – this act of mercy eventually leads to Ken being killed by Harry while trying to protect Ray.

Ray, meanwhile, ends the film having sustained multiple bullet wounds, but still uncertain about whether he will live or die – he is still in between, still in purgatory, his redemption as far away as ever. In a way, Ken’s death while protecting his friend could be seen as his attempt to redeem himself for all the crimes he has committed as a contract killer.

3. Leon: The Professional (Luc Besson, 1995)

Luc Besson’s Leon: The Professional stars Jean Reno as the eponymous hitman who has no worldly attachments until he saves twelve-year-old Matilda (Natalie Portman) from Gary Oldman’s scenery-chewing, pill-popping gangster.

From then on, Besson presents a classic coming-of –age narrative, with two unusual elements: firstly, the coming-of-age in question takes the form of Matilda’s induction into the world of killing for hire, and secondly, Leon has as much growing up to do as Matilda.

In a way, Leon is still very much an innocent, despite the nature of his work. He is illiterate, all his financial affairs are handled by an older mentor (who, it is implied, is ripping him off) and overall his life is one of childlike freedom and simplicity.

He has few possessions, and virtually nothing to tie him down – no job, no friends, no romantic entanglements – but it is through Matilda that he learns to care about life, and has an impact on someone other than himself.

2. The Wrestler (Darren Aronofsky, 2009)

Aronofsky’s The Wrestler focuses on Randy “The Ram” Robinson (Mickey Rourke), a washed-up wrestler who was a star in the ‘80s but now works in a supermarket and takes part in independent wrestling matches at weekends.

Over the course of the film, Robinson attempts to re-establish a relationship with his estranged daughter and seeks romance with Marissa Tomei’s stripper Cassidy.

After both Cassidy and his daughter (Evan Rachel Wood) reject him, he realises that the only place where he fits in is in the ring.

The Wrestler is about wanting to redeem oneself in one’s own eyes alone – wanting to be recognised for being great at a single thing, wanting that one moment (however brief) of glory, even at the cost of one’s life.

Randy seeks to atone not for any particular sin, but simply for his failure and the mediocrity of the life that he has become trapped in.

1. The Redemption of General Butt Naked (Daniele Anastasion and Eric Strauss, 2012)

Are there some crimes that can never be forgiven? Are there some criminals who can never be reformed? Just how far down the road of barbarity can someone go and still be able to come back? These are not original questions, and The Redemption of General Butt Naked is not the first film to ask them, nor is it the hundred and first.

What makes this film unique is that it explores these questions not through fictional characters, but through the story of a real man. Joshua Milton Blahyi was a Liberian warlord who murdered thousands of people and earned the nickname “General Butt Naked” due to his and his troops’ habit of fighting naked.

That alone would make him a compelling subject for a documentary, but what earns The Redemption of General Butt Naked its place on this list is what he did next.

After the end of the Liberian civil war, Blahyi renounced violence and decided to dedicate his life to making amends for what he had done. Now, he travels around the country that he once ravaged, seeking forgiveness from his surviving victims and trying to help his former child soldiers rebuild their lives.

Anastasion and Strauss’ documentary explores the reactions of those he seeks out, the crimes he committed, and the questions surrounding whether or not Blahyi is sincere in his desire to do good.

Author Bio: George Jones is a writer and musician from Essex, currently living in Wales. In addition to writing about film, he makes Youtube videos under the name ThePeculiarLefty.