Born on March 23, 1910, Akira Kurosawa would eventually become the greatest contemporary Japanese director, and one of the most important filmmakers globally, with more than 30 films that won awards both in Japan and internationally.

Kurosawa studied western civilization in depth, and embedded a plethora of its elements in the Japanese culture, in the most artful way.

The result was the creation of his own unique style of filmmaking, which later returned the favor by influencing western filmmaking. He did not hesitate to use the work of western classics like William Shakespeare, Maxim Gorky and Fyodor Dostoevsky, adapting them to feudal Japan, while western filmmakers did not hesitate to remake his movies in order to create great films.

In that fashion, Sergio Leone’s “A Fistful of Dollars” was based on “Yojimbo” and John Sturges’ “The Magnificent Seven” on “Seven Samurai”. Furthermore, George Lucas never tried to conceal the fact that “Star Wars” was inspired by “The Hidden Fortress”.

Here are 15 of the most distinct scenes of his filmography. Please take caution, before reading, because the list contains many spoilers.

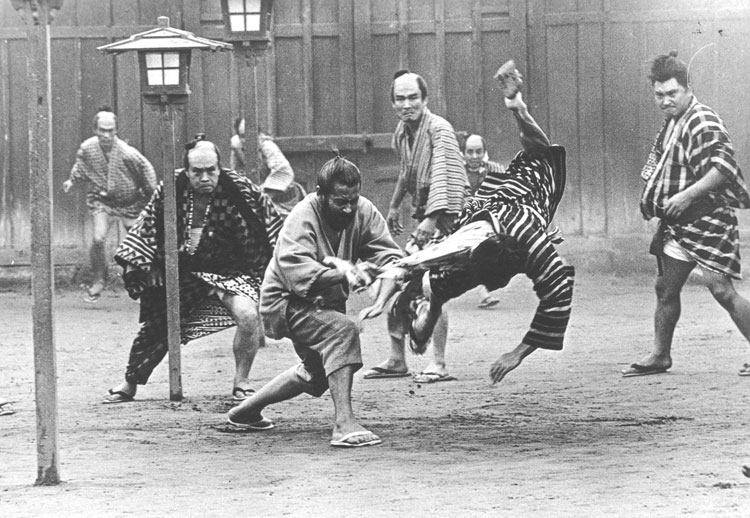

15. Red Beard attacks the guards (Red Beard, 1965)

Red Beard proves to be a martial arts expert as he uses his knowledge of human anatomy in order to break the arms and legs of the guards of the brothel he and Yasumoto have assaulted, in order to rescue young Otoyo.

They succeed, but as they leave, Red Beard apologizes to Yasumoto for his use of violence, informing a stupefied Yamamoto that a doctor must do no harm to others, while the guards lie on the ground moaning.

The scene stands apart from the serious nature of the film in the most amusing fashion, proving Kurosawa’s sense of humor. Furthermore, Red Beard’s auto criticism is a recurring theme of the film, exhibiting the humanistic and existentialist nature of the film.

14. Chubo is about to die and Otoyo and the cooks cry his name into a well (Red Beard, 1965)

The little thief Otoyo takes care of is about to die after committing suicide. Suddenly, a mourning sound is heard from outside. The eerie noise comes from the cooks, who cry Chubo’s name down into the well, in a practice they believe reaches the center of the earth where souls go before perishing. In their minds, they are calling back his soul in order to save him, and Otoyo, acknowledging their efforts, joins them.

As Kurosawa again exhibits the humanistic and existentialist nature of the film, he also reveals his prowess in cinematography. The scene initially looks like a single shot as the camera is turned up towards the cooks from the bottom of the well. However, subsequently it pans down the walls and shows the cooks’ reflections in a magnificent and uncanny scene.

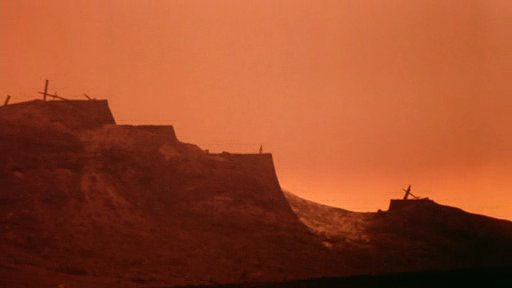

13. During the end of the film, the blind Tsurumaru walks to the edge of a large cliff (Ran, 1985)

Kurosawa has isolated the young man as he moves toward the precipice, almost falling over. The camera, however, shows the audience what Tsurumaru cannot see, but only feel: the barren world where his miniscule existence resides, which is placed somewhere in the center of it.

The scene is a distinct antithesis to the initial one of the film, with the green field and the blue sky, and in that fashion, it elaborately concludes the film, visually presenting the emotional climax of both “Ran” and of Shakespeare’s “King Lear”.

The scene is also a perfect example of how Kurosawa uses jump cuts, with them moving to a slightly later chronological point in the scene, creating an effect of acceleration and disorientation as they present a constantly shifting world.

12. The woodcutter enters the forest and the camera points at the sun (Rashomon, 1950)

In a flashback that presents the case from the woodcutter’s point of view, the protagonist enters and walks through the woods carrying an axe. The 16 shots that make the scene show both the woodcutter and the sun through dense trees.

In the first aspect, his movement is depicted as both from left to right and right to left. This tactic is a metaphor for the case the film deals with, where nothing is predetermined and certain. As the woodcutter’s movement differs according to the point of view, the same applies to the case.

The second aspect, the shooting of the sun, was considered taboo up to that point and cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa is credited with the “first” use of the effect. The sun is shown through thick branches, with the camera turned upside down. The way the sun is depicted is as obscure as the way truth is presented in the film.

11. Washizu and Miki are lost in the forest (Throne of Blood, 1957)

After listening to the Forest Spirit’s prophecy, Washizu and Miki desperately try to find their way out of the forest, which is filled with fog that confuses them even more. After hours of galloping through the fog, the two of them realize that they have been moving in a circle.

At the same time, the recurring theme of the horse hoofs breaks the utter silence, followed by thunder and an ominous laughter, which gives the impression that the forest is actually mocking the two of them.

The scene is highly metaphorical. The impatient and powerful hoof sound is a metaphor for the characters’ ambition that has grown after the prophecy. The fact that they move in circles is a metaphor for the result of their wishes, which are doomed to fail. The laughter that is heard, as the forest does not let them leave, is a metaphor for the notion of revenge, which is one of the film’s main themes.

Technically, the scene displays Kurosawa’s prowess in using sound and silence, with the two aspects becoming key features of the film in their distinct symbolism.

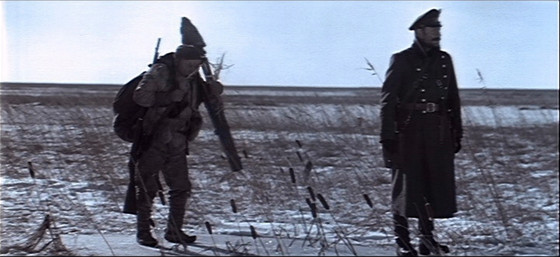

10. Dersu and the Captain go out to chart a frozen lake (Dersu Uzala, 1975)

As the two of them reach the lake, they are overcome by the terrifying spectacle, as all the harsh nature of the Siberia reveals itself, particularly through the ice-cold wind. Both of them are scared, but the Captain, as a military man, does not show his fear, which is instead communicated to the audience through the narration of his thoughts.

However, as soon as Dersu indicates that they should leave immediately because the wind will cover their tracks, the Captain also shows his eagerness to leave. When they finally manage to move, after Dersu’s exhortations, the Captain’s compass fails, and their fear becomes even worse.

Kurosawa films the Siberian cold in the most horrendous fashion ever. The cold is actually an enemy, almost a physical presence, in front of which both Dersu and the Captain cannot do anything but stand in awe. As the scene progresses, the danger becomes more tangible, with the cold transforming the film into a thriller and the agony reaching an apogee.

9. The two rival gangs confront each other at the town’s crossroads. Sanjuro is looking at them from above (Yojimbo, 1961)

Kurosawa was one of the first to implement the new, at the time, Cinemascope format and this scene is a distinct example of the fact. He places each group of gangsters in the foreground, but at the edges of the rectangular shape of the format, leaving the middle empty for Sanjuro to appear there in the background, watching the events unfold from atop a watchtower. With this ingenious technique, he actually manages to change Cinemascope’s frame format.

The scene is a clear indication of the differences in the characters of Sanjuro and the gangsters. They are cowards, imbeciles, and full of big words but spineless behavior. Sanjuro, on the other hand, is superior in both skills and intelligence, despite the fact that he is equally amoral.

As he watches from above their hilarity, his amusement mirrors Kurosawa’s amusement at the absurd and self-destructive nature of humans.