8. Oldboy

Oldboy is a 2003 South-Korean film directed by Park Chan-wook. It is based on the manga of the same name and has become a cult film, with many of its sequences often homaged or referred to by cinephiles and fans alike. In 2013 it was also remade by American filmmaker Spike Lee.

The themes of the movie are revenge and the Oedipus complex: following an unexplained imprisonment of 15 years, the protagonist Oh Dae-su (a name chosen for his similarity to “Oedipus”) is released into the world with the instructions to discover who his captor is and why he did what he did.

The mysterious man is revealed to be Lee Woo-jin; his motives are revealed in flashbacks that display the horrific trauma behind his actions. The most striking flashback is located towards the end, and shows young Woo-jin’s sister hanging from a bridge while being hold by her crying brother. She asks him to let go, and then reaches for Woo-jin’s camera, shooting a photo of herself right before the fall.

An extremely striking moment, full of emotion and tragedy, a death as memorable as many of those depicted in the Greek tragedies the film is inspired from.

7. Casablanca

“We’ll always have Paris” is one of the most memorable quotes Casablanca gave to the world; it is spoken in the last scene of the movie and is a reference to a flashback earlier in the movie, when Humphrey Bogart’s Rick, drunk and melancholic, remembers the happy times he had lived with Ilsa (an unforgettable Ingrid Bergman) in the City of Lights.

One of the most classic flashbacks in cinema, and one who set the tone for many others that followed, it opens with the musical cue of the Marseillaise over a shot of the Arc de Triomphe (just to make sure the spectator knows he is watching Paris) and a typical driving shot of the time, with a pre-filmed street behind the actors and the car.

The sequence then shows the two lovers in their apartment, then in a café, and more in general living their happy life until war and the occupation of France by the Germans.

The flashback serves as a clear break from the main narrative, and enhances the characters’ personality by revealing how much of a past they have in common. In the most “classic” of “classic movies”, this flashback sequence stands as one of the memorable sequences, and it is fundamental in creating its tone and the unique atmosphere around it.

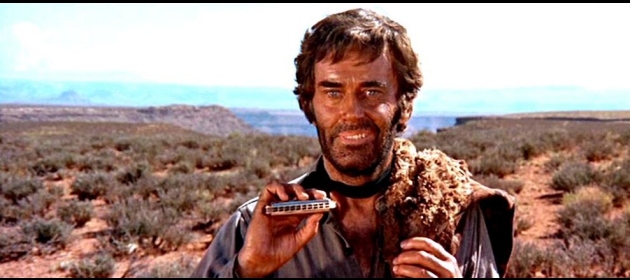

6. Once Upon a Time in the West

The flashback at the end of Once Upon a Time in the West is highly dramatic; it has the extremely slow pace of Sergio Leone’s most memorable moments and masterfully delivers a final hit to the viewer’s stomach after more than two hours of classic western sequences.

The flashback comes right before the climax of the duel between Harmonica (Charles Bronson) and Frank (Henry Fonda); it is a moment particularly full of tension, in which the events of the film come to their conclusion through the final face-off of the two characters.

After Sergio Leone has shown us at length the almost sculptured faces of the two man, and right before they shoot, the camera moves closer to Harmonica’s eyes. The flashback then begins, finally revealing the reasons behind the character’s actions and his hatred for Frank; set many years before, the sequence shows younger versions of the characters and their encounter.

After the viewer has gathered all the information he needs to understand what happened, the duel abruptly takes center stage again, and quickly ends. A masterfully executed sequence, the flashback of Once Upon a Time in the West is among the most iconic moments from the filmography of a director who made iconic moments his signature trait.

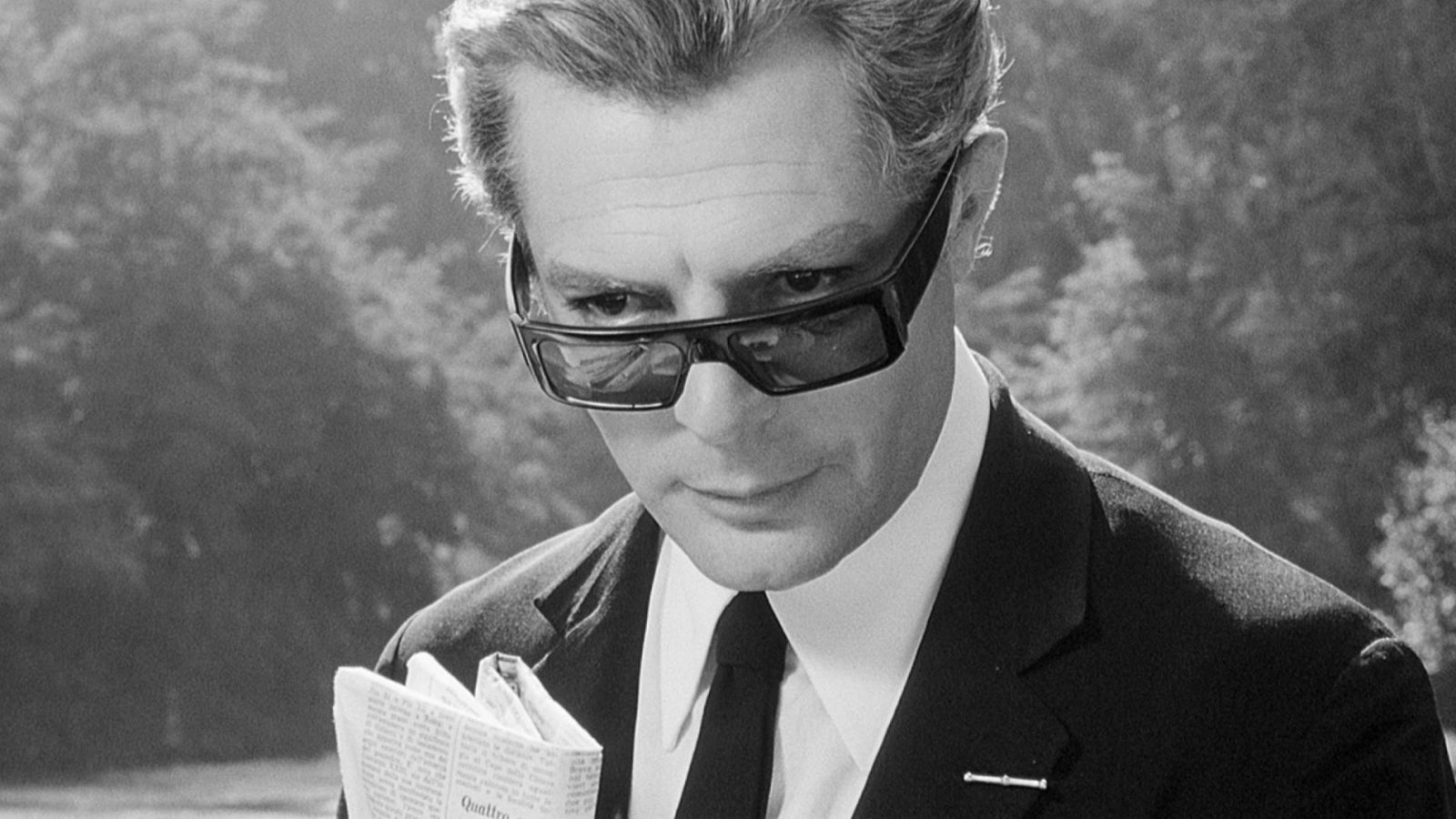

5. Hiroshima Mon Amour

The end of the 1950’s saw the release of many films that set the tone for the Nouvelle Vague, even when they actually were not part of that movement. Hiroshima Mon Amour is among those films.

Directed by Alain Resnais and released in 1959, the movie is visually experimental, especially in its first sequence, a series of close-ups and unexplained longer shots, shown while we hear the two main characters speak in overdub. Hiroshima Mon Amour is one of those of films one can truly say opened new doors for filmmaking.

Narratively, its main theme is memory and its fallacy; flashbacks, both short and extended, are extensively used as the two nameless protagonists, a French woman and a Japanese man, share a brief love story and talk to each other.

The specter of war is behind their every word: for the man, the tragedy of Hiroshima, for the woman, the occupation of France. The longest flashback of the movie is a wonderful sequence in which the woman tells of the shameful affair she had during the war with a German soldier.

Hiroshima Mon Amour and its non-linear narrative are a staple of the evolution of cinema in the second half of the century; it is apt that a film so revolutionary had to thematically deal with the greatest tragedy of the first part of the century, World War II.

4. Rashomon

A masterpiece of storytelling, Rashomon is the most referred to movie when it comes to the themes of unreliable narrators and false flashbacks. Directed by Akira Kurosawa in 1952, the film is based on the short story “In a Grove” by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa and centers on the murder of a samurai. In a court, various characters linked to the event tell their version of what happened.

The twist is that the stories (which involve the raping of the samurai’s wife as well) don’t coincide at all. The samurai himself gets the chance to testify when a medium is summoned in the court to make him speak through her; additionally, a stranger (a woodcutter) also tells his version of the story to a commoner whose arrival at the Rajōmon gate opens the film.

The use of diverging flashbacks helps the film to make a point about the concept of truth in opposition to interpretation. Whose to say what the reality is if men cannot concur on a version of it? The characters represent human ambiguity and shadiness, and Kurosawa aptly decided not to resolve the matter by revealing an objective truth behind the murder.

3. 8 1/2

Dreams, memories, soul. One of Fellini’s masterpieces, 8 1/2 tells the story of one of the director’s alter egos, Guido Anselmi, played by Marcello Mastroianni. Caught in an artistic and existential crisis, he often goes back to his childhood memories and seeks solace in them.

A flashback sequence in the middle of the movie is particularly revealing, and is triggered by the words Asa Misi Masa written on a chalkboard by Mademoiselle Maya, under the effect of telepathy. A mesmerizing music plays as the memory unfolds, and the origin of the words is revelead as a sort of childish formula told to Guido while in bed.

2. The Godfather Part II

The second movie of the Godfather trilogy fully expressed the potentiality of what a sequel could do, and is now often referred to as the epitome of what the second installment of a franchise must do in order to work, and also surpass its predecessor.

The first chapter of the Corleone saga had covered eleven years of the family’s life of crime, and focused on Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando) and his son Michael (Al Pacino), who initially finds difficulty in adapting to the ways of his father and his brothers but ends up becoming the new “Don” and the undisputed boss of the New York mafia.

By the end of first film, Brando’s Vito Corleone, the titular godfather, already an old man, was dead; still, the legendary aura of his persona brought Francis Ford Coppola and Mario Puzo (the films’ screenwriter and the writer of the books they are adapted from) to reprise the character by telling the story of his younger days.

The film intertwines a main “sequel” narrative, in which Al Pacino’s Michael defends his newfound reign of crime, with “prequel” sequences, a series of flashback that cover the parallel rise of Vito (Robert DeNiro in one of his best performances) in early 1900’s New York.

1. Citizen Kane

The definitive masterpiece of Orson Welles (as well as his feature film debut), Citizen Kane defined the heights that cinema could aspire to.

The film introduced many techniques that were basically new to the film world (depth of field in particular), and also gave an excellent example of fragmented storytelling. Citizen Kane is built around a mysterious figure who has just died, and his life is not reconstructed in a linear and completely reliable manner; instead, the story unfolds through the testimonies of the people who knew him.

The true nature of the Charles Foster Kane (a character famously built around William Randolph Hearst, a renowned business man and newspaper tycoon) never truly unfolds, as his old friends, associates and lovers take their turn in telling a section of Kane’s larger-than-life existence.

The various stories convey unreliability and differentiate the narrative which seems to change at least a little for every narrator; of all the flashbacks in this flashback-based movie, perhaps the most important is the one about Kane’s childhood (or at least, it becomes the most important after viewing the ending).

Through a “picture in picture” technique, the sequence creates a contrast between young Kane’s playfulness and the adults who represent the harsh world he will live in for the rest of his life.

Author Bio: Riccardo Basso is an Italian cinephile specializing in Humanities and Philosophy. He has only recently started writing about his favorite interest, cinema, but wishes to continue doing it (just don’t tell his cinephile friends he has seen every 007 movie at least three times).