We are curious by nature, and that’s one of the many things that make us human. We want to know how things work and why. Our curiosity has taken us very far; we started using bones as weapons and now we even have plans to colonize other planets. It’s amazing what can happen when you give a species the ability to think creatively. Science, philosophy, art and religion are just some of the methods we invented to explain the world around us.

There are things we don’t understand; for instance, we don’t know what will happen when we die or what love actually is, but we compensate our ignorance with our ability to theorize, to think and come up with answers. Of course, most of the time those answers might be just temporary ones, subject to perpetual change and improvement, but that’s part of the human experience, and it means that we still have a lot to learn and understand, which is an exciting and frightening realization.

Philosophy is about learning how to live, how to interpret things, how to develop oneself, and how to understand the world, which can sometimes prove to be very confusing. Here I present you a non-hierarchical list of 15 great comedies that might give you insight on the nature of reality, and help you in your journey to understand life. Don’t forget to laugh!

1. Closely Watched Trains (Jirí Menzel, 1966)

“Closely Watched Trains” is probably the most outstanding film of the Czech nova vlna (new cinema) that flourished, just like many other artistic revolutions during the 60s. Directed by Jirí Menzel in 1966, the film tells the story of Milos, a young man who begins to work in the local train station like his father and grandfather before him, and is eager to discover the secrets that lie in the female body.

As most of the revolutionary movements in cinema, the nova vlna is eminently political, and that’s one of the reasons it was ended with the Soviet invasion of Prague and, thus, the fall of the liberal regime. The film is set during the Nazi invasion, but the war is only a backdrop to the real drama of the film.

Filmed with an existentialistic approach to the absurd, the film touches on a wide variety of subjects, like the influence of the family tree on the life of the individual, the search for accomplishment, erotic desire, and suicide with a very light-hearted eye and an exquisite sense of humor.

Sexuality is the main axis around which everything orbits, and that can be said about life and about “Closely Watched Trains”, whose visual allusions to sex and masturbation could have easily been taken from a Freudian dream. After a failed attempt to lose his virginity with his friend Masa, Milos tries to commit suicide (and fails, again), drawing the mysterious and fascinating link that separates sex and death, which has fascinated our race since the dawn of consciousness.

2. The Meaning Of Life (Terry Jones, Terry Gilliam, 1983)

In the form of various thematic shorts, Monty Python’s ‘The Meaning Of Life” explores the many mysteries that surround life. Going from birth to afterlife, the film touches on politics, economy, metaphysics, existentialism, science, religion, and many other obsessions.

Silly as always, Monty Python has given us a very thorough on most of the obsessions we all share as a human race, but mainly the fear and fascination that death provokes into us. The structure of the film, divided in seven acts or chapters, allows for a myriad of subjects involving death to be touched on and played with, never letting the silliness of it all get out of hand and absorb the most complex and profound moments.

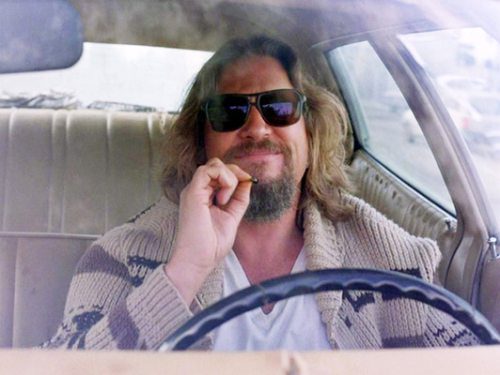

3. The Big Lebowski (Joel and Ethan Coen, 1998)

“The Big Lebowski” is probably the most iconic film by the Coen brothers, and is a hilarious tale about the struggles of life and the contrast between what we want of the world and how the world is the motor of all of our actions.

Filmed in 1998 and starring Jeff Bridges in the role of The Dude, ‘The Big Lebowski” is a film about a man who is confused with a millionaire by some thugs who piss on his carpet. Where do we find meaning? In philosophy and art, as portrayed in the film by nihilism and the fluxus movement? Maybe, but there isn’t one single right answer.

It’s a postmodern film in the way it portrays its hero; The Dude does not fight for sublime ideals like beauty, justice or peace, all he wants is his carpet replaced. The Dude is just another human being, living life his own way. The search for meaning doesn’t necessarily take to the darkest or brightest confines of the human soul; it’s about being at peace with yourself, feeling comfortable at the place you are at, and if a carpet brings you that, then it’s just as worthy of protection and worship like an altar or a crucifix.

“The Big Lebowski” gives importance to the individual, as each of our mannerisms and idiosyncrasies mean something, for they are what make us who we are.

4. Songs From The Second Floor (Sånger från andra våningen) (Roy Andersson, 2000)

“Songs From The Second Floor”, directed by Roy Andersson at the beginning of this century, is an existentialistic comedy that extrapolates to the point of absurdity many of the defining elements of our era. It is the first film of Andersson’s trilogy about the human condition, followed by “Du Levande” (2007) and “A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence” (2014).

Ingmar Bergman was famous for his profound and deeply psychological dramas, and we could easily argue that Andersson (who also happens to be Swedish) is his alter ego. If Ingmar Bergman reacted to the fear of death, and to the anxiety that is felt once concepts like God or fate lose their meaning with despair and suffering (as if he were some sort of spiritual successor of Dostoevsky), Andersson assumes the other side of the duality and finds in the absurdity of existence something to laugh at, and that’s what we see in his trilogy. It is between the dichotomy of Bergman-Andersson that we realize that both crying and laugher share the same root.

In a particular way of storytelling, the film follows various characters that go through all sorts of ridiculous situations, like the owner of a furniture shop who blames the sickness of his son on poetry. While also allowing the spectator to have the philosophical insight one might have while watching a Bergman film, Andersson crafted a great, easy to watch, deeply human film.

5. Duck Season (Fernando Eimbcke, 2004)

“Duck Season” is Mexican director Fernando Eimbcke’s opera prima and it beautifully portrays love, friendship and dreams. Flama and Moko are two friends who spend a Sunday together in a Mexico City apartment while mom’s away. A friendly and young neighbor who is a very bad cook, a pizza delivery man who doesn’t make it on time, and a painting of ducks are just some of the characters that appear throughout the film and give it its unique feel.

With a melancholic eye, Eimbcke made a film about the pain that comes with divorce, the transition between being a child and a teenager, and the lost hopes and many other difficult complications of life.

6. Birdman (Alejandro González Iñarritu, 2014)

Alejandro González Iñarritu has become one of the most reputed and respected directors of our time. It was with “Birdman”, a film that explores with a critical eye today’s society, that he received his first Academy Award.

The main subject of the film is the distinction between art and entertainment. “Birdman” tells the story of Riggan, an actor who got famous by playing the role of Birdman, a famous movie superhero, and is now trying to re-vindicate himself as an artist trough the theatre adaptation of a Raymond Carver story.

In this dichotomy we find a critique toward the current state of things in the film industry. Hollywood, more than a factory of dreams, seems today to be some sort of recycling plant swarming with sequels, reboots and remakes, all safe bets for the producers, and “Birdman” attacks that tendency that has left audiences with a bunch of fun but shallow films (and that explains much of the displeasure the film provoked in many of its viewers).

7. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (Terry Gilliam, 1998)

“Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” portrays the landscape of drug use in the post-60s world. After words like ‘love’ and ‘peace’ lost their meaning, and after it was clear that drugs weren’t the magical substances that could instantly grant illumination and inner peace, a demotivating feeling appeared. Johnny Depp plays Raoul Duke, an avatar for Hunter S. Thompson, the legendary father of gonzo journalism.

The film is crazy in its depiction of drugs, and every ingestion takes to a bad trip of mythical proportions. People turning into bloodthirsty dinosaurs, an acute paranoid state, and a suicidal appreciation of music are just some of the consequences of the acid, the grass, the , the coke and the many other drugs taken by Duke and Dr. Gonzo, his lawyer and trip companion.

There is a significant moment of deep insight in a monologue by Duke, where he reflects on 1960s San Francisco. Did Timothy Leary got it all wrong? Could we really find salvation in chemicals? Isn’t this search for illumination just another attempt to forget about ourselves?