If there is a tool unlike any other, it would be the ability to hold a conversation, to project what’s on our mind onto the lives of others, hitting them with an incredibly profound impact, for they have lived it according to their own words.

Through these provoking aspects of our thoughts, we manage to shed light onto visceral, random, popular and obscene subjects that we don’t normally talk about. Cinema as a platform withstands with effects, editing and images, but the core of an argument that is constructed through words can make us experience the whole range of emotions of which we are capable.

1. Before Midnight (2013)

Natalia: It’s just like our life, we appear and we disappear. We are so important to some, but we are just passing through.

About every film Richard Linklater has ever made could go down as the best in terms of dialogue, but this in particular exerts a sense of realization not shown in his other works.

The two other films that started this trilogy were still young and rapid, more preoccupied with making a lasting impression with the two leads, presenting the world with the dynamic of what a conversation in traditional cinema can be like. With “Boyhood” (2014), it was all about mankind living through an order of experiences and stages; with this film it is all about what is said and not unsaid.

Before this, Jesse and Celine had room for silences, to opt out of saying something hurtful, resourcing themselves to something more damaging: the sound of silence. Instead, here they’re aware of their power and influence within their relationship, and there is a sense of compromise that they can’t escape. They recognize the heavy aspect of love that plays a part in their relationship, not admitting it would be defacing their love and the constructing aspect of the length of their relationship.

The resounding thing here is to show how powerful dialogue is through conversation; perhaps it is the most powerful tool for knowledge and understanding all sort of things in the universe that work on our level.

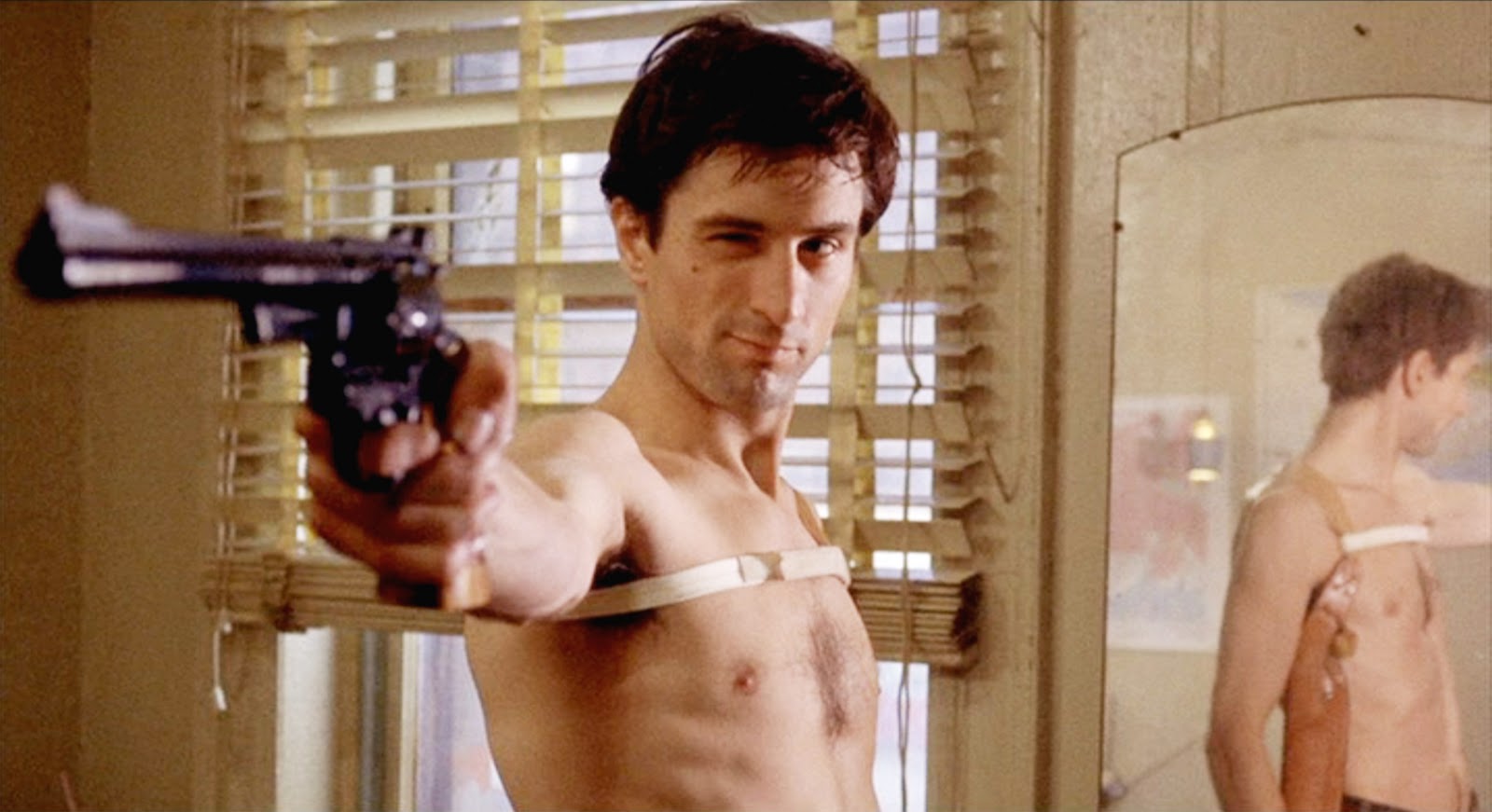

2. Taxi Driver (1976)

Travis Bickle: You talkin’ to me? You talkin’ to me? You talkin’ to me? Then who the hell else are you talkin’ to? You talkin’ to me? Well I’m the only one here. Who the fuck do you think you’re talking to?

“Taxi Driver” doesn’t have many turns in action and spectacle, instead focusing on the intimate rebellion that is brewing within Travis Bickle, and how his role is key to solving, according to him, the filth in society. He is a disturbed source of awkward comments and remarks that end up alienating everyone that surrounds him.

Travis isn’t an easy going guy; rather, he is an archetype through which dialogue conveys an intention that doesn’t escape the film or the world it has created. Robert De Niro channels his usual physical self with gestures, postures, clothes, and even shades and a hairstyle that define him. Like a carcass that has found its body, that is what Travis Bickle is: a man with a mission.

At first numbed by the world that envelops him, Travis starts assimilating into this skewed world, and instead of making himself another puppet of sorts from this filth, he rises into a call to action and starts finding redemption and clarity in his role through the nature of a young Jodie Foster.

Through her eyes, he realizes there can be no more excuses. He starts dismembering all possessive schemes of society to make an uprising and change the fate of the world he sees, yet not the world it is. This is a decisive choice that enables him to pass as a mere taxi driver, when the source of his bravado later shaped films like “Drive” (2011) or “Cop Car” (2015).

3. Jerry Maguire (1996)

Jerry Maguire: I love you. You… you complete me. And I just…

Dorothy Boyd: Shut up, just shut up. You had me at ‘hello’.

True, it’s full of clichés and conventional twists that envelop the film in predictability (as with any Cameron Crowe film), yet it’s a story coated with so much heart and endearing turns that it can stir something deep beneath the tough crust that is our resilience to emotion.

The power of this film is in carving Tom Cruise into full-preacher mode, preparing him for what he will later fully control physically in “Magnolia” (1999). Here, the dimension of physicality and the dialogue it comes with it cedes expectations to the strength of the sheer emotion and softness that finds Cruise, allowing us to wobble at every scene.

“Jerry Maguire” fits the mold at the start of the film, describing every career-obsessed sports agent. Concerned, like the people he represents, about the speed of the hit, he is soon bedazzled by the amount of moral filth he finds in what should be a “Field of Dreams”-esque experience, where he writes a manuscript that changes his entire self more than it changes the outside world. And like every time we attempt change, temptation and failure are the first orders of the day for Jerry Maguire.

Here, there are no plot twists in the vein of Christopher Nolan, but instead, the lines that Jerry Maguire (there is a necessity in saying his whole name, not just Jerry or Maguire) speaks begin to change himself as he says them. He doesn’t find love, he manufactures it, fights for it and a clear personification of that fight is the existence of Cuba Gooding Jr. as Rod Tidwell.

The necessity that invokes his eclectic nature is what summons all of us into clichés, predictions, roses and unfounded gestures, and is what makes us fall in love with love.

4. Magnolia (1999)

Donnie Smith: We may be through with the past, but the past is not through with us.

Three years later after Tom Cruise’s fine work in “Jerry Maguire”, Paul Thomas Anderson conveyed one of the most intricate stories, with Cruise at the helm of the action. “Magnolia” works on multiple narrative levels, finding all the threads aligned to a single concept: There are no coincidences. There can´t be.

This exercise of accident and the will of men colliding is perfectly portrayed in the introduction of the film. One can watch the narrative setting at the start of the film, grasp the intention of all of it, and not watch the rest of it, yet still grasp the whole intention of the movie. This is a true masterstroke that translates still booklines into live imagery. Like Lewis Carroll, he sheds light onto their subject matter, even before the latter even started with stories like “Through The Looking Glass” or “The Circular Ruins”.

Inside the story, where personalities interact with the fate of one another, the dialogue between characters reveals the torment of their worlds. A tough exercise, because Anderson manages to carve humanities through conversations with strangers, as well as also managing soliloquies from the star-studded cast. Each with their own torment, they make us start to see how this mayhem is shared rather than isolated.

The MVP here is Cruise with his portrayal of a hateful and masochistic man with vertical and phallic postures and gestures, only to be radically transformed. It wasn’t an interview that detonated the fall of his behavior, but rather the reflection of judgement and seeing a void, for he has living in an emptiness of speech. He finds intimacy with his father on his deathbed and confronts his demons in a room with another person rather than other people.

5. The Night of the Hunter (1955)

Preacher Harry Powell: Would you like me to tell you the little story of right hand, left hand? The story of good and evil? H-A-T-E. It was with this left hand that old brother Cain struck the blow that laid his brother low. L-O-V-E. You see these fingers, dear hearts? These fingers has veins that run straight to the soul of man — the right hand, friends, the hand of love.

This is a strange film, one that’s so advanced in aspects of editing and composing images. We are presented with Preacher Harry as an opposing dichotomy, shedding the idea of religion as a source of purity, where we can see in his speech that evil comes from strange and dark places within ourselves.

The children here extend their line of purity to their actions, being representative of their soulfulness through acts and timed words, living the verbal flow of things to Preacher Harry and his enchantments, in a pre-McConaughey era where gibberish about philosophy and life could be casted into the south with a sense of menace, instilling a persecution, a hunt.

6. The Godfather (1972)

Don Vito Corleone: I’m gonna make him an offer he can’t refuse.

If a film can have more reverberance for its arguments, rather than for its imagery, sound or obscene spectacle, we are talking about a work that lasts as long as “The Godfather” itself has lasted, as one of the finest films of its time and any other time it has touched and will continue to touch.

Marlon Brando and Al Pacino are the sources of the best lines cinema has seen, and every reaction or argument they have is resolved as a story itself. The film is shaped in a way that has many stories revolving about the conflict of family and right and wrong.

This is a fine example as to how polarities and dichotomies extracted from the protagonist and the antagonist complement each other finely, rather than negating the other. An example that can translated to the small screen is the work of Bryan Cranston and Aaron Paul on “Breaking Bad” (2008). Their modern take on the magnetism of “The Godfather” is clear evidence of the effects of this work and about any work that has come after this film.

7. Revolutionary Road (2008)

John Givings: Hopeless emptiness. Now you’ve said it. Plenty of people are onto the emptiness, but it takes real guts to see the hopelessness.

The road Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet transit once again in this film is perhaps the hardest they’ve had to cross together. The iceberg here extends its coldness throughout the atmosphere with a menacing knowledge. Unlike “Titanic”, here the menace is more dangerous: it is known. And people, aware of the danger and still playing with it, are perhaps more dangerous than the “it” factor of surprise.

Frank and April compose soullessness like no other spousal dichotomy. The dialogue here works as another protagonist. Frank crafts his speech from the point of a man, that once he finds liberty right around the corner, he realizes that his sole potential and ability lies in something he doesn´t love, but yet is the only thing he does best. It’s a profound feeling of reflection onto his marriage.

April, on the other hand, is the element that anchors the past with tormenting memories of a potential family. She is the one who experiences loss within the very linings of her organism, whereas Frank deals with it in a complete detachment.

The insults between these two are not foul-mouthed words, but reclaims of better times, constructing each their point of reality, overlapping a dramatic arch that attends the vigilant and perpetual needs of love.