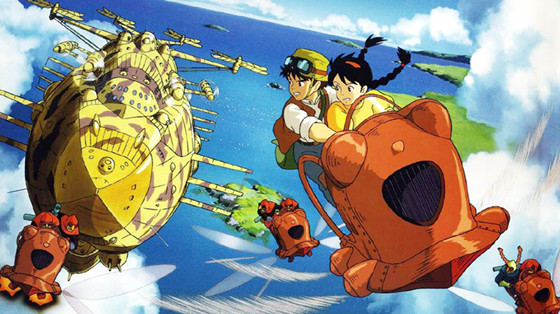

7. Castle in the Sky (Hayao Miyazaki, 1986)

Laputa is a floating city in the sky that once used to be great. In its prime, it was technologically advanced, while its inhabitants were also living in perfect harmony with nature. Eventually, due to a disaster, they were forced to abandon it, and now it floats around, deserted.

Sheeta is a young girl sought by pirates and the military, due to a crystal necklace she owns that is supposed to be the key to discovering Laputa and revealing its secrets. Eventually, Sheeta ends up with Pazu, who also dreams of seeing Laputa, and the two of them try to reach the floating city before their chasers.

Miyazaki directs a film that entails many of his distinctive traits, but particularly the ones regarding co-existence with nature and the futility of war. The first one is presented through the city’s past, while the violent clashes between Sheeta, Pazu, their pirate friends, and Muska and his soldiers, exemplify the futility of armed confrontation, the worthlessness in the struggle for power.

Furthermore, “Castle in the Sky” incorporates elements of a coming-of-age film as Sheeta and Pazu try to cope with the world, maturing through the fact that they have no parents to take care of them.

The film features astonishing drawing and animation, with the battle scenes and the end sequence standing apart.

6. Akira (Katsuhiro Otomo,1988)

Katsuhiro Otomo’s magnum opus, based on his own manga that stretches for more than 2000 pages, is one of the landmarks of the anime genre, being universally acclaimed and having garnered a large cult following.

Neo-Tokyo is a post-apocalyptic megalopolis that was built near the remains of the old city, that was destroyed during World War 3 by a nuclear attack. There, a motorcycle punk gang headed by Kaneda, is in constant fights with another gang, whose members call themselves “Clowns”.

Unfortunately, Kaneda and his comrades find themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time, in an incident that includes government officials and some mysterious creatures. Furthermore, the government later arrests Tetsuo, a member of the gang. The film is the epitome of post-apocalypse, one of the genre’s most cherished themes.

Otomo describes a dystopian reality where gang wars, violence, abandonment, fear, and death synthesize the environment of a decaying metropolis. Completely hand-drawn, “Akira” is nevertheless an audiovisual masterpiece, incorporating exquisite animation and a vast palette of colors to depict the futuristic and industrial environment of Neo-Tokyo.

Furthermore, the permeating violence, the not-so-obvious messages, and the complex story established the fact that anime were not only addressed to children and young teenagers, creating in the process a completely new market for the category.

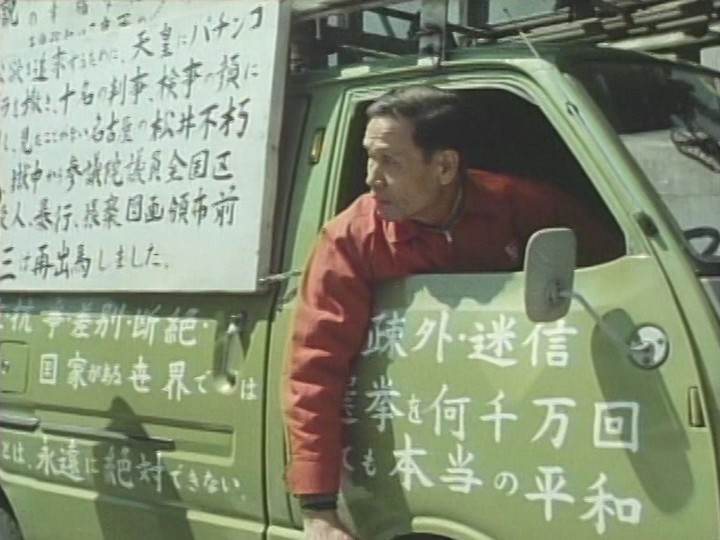

5. The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On (Kazuo Hara, 1987)

The preposterousness that was the rule in a plethora productions of the 70s continued up to a point in the 80s, and this documentary is a great specimen of the tendency.

The title follows Kenzo Okuzaki, a self-proclaimed anarchist, in his quest to find the reason behind the execution of two fellow soldiers at the end of World War II, while Japan had already surrendered.

The absurdity of the film lies with its protagonist, a truly obnoxious individual, who is willing to resort to extreme measures in order to achieve his goal. In that fashion, he physically attacks those who do not answer his questions, even if a number of them are incapacitated older people.

Furthermore, he threatens everybody, he constantly proclaims the fact that he was arrested for circulating pornographic material regarding the emperor, and even resorts to forcing members of his family to pose as relatives of the actual victims, in order to be more persuasive in his interviews. Overall, his actions are so extreme that it’s somewhat hard to believe that this is actual footage and not fiction.

The documentary won a number of awards from festivals all over the world, both for the director and the film on a whole.

4. Kagemusha (Akira Kurosawa, 1980)

In 16th century Japan, the daimyo of the Takeda clan, Shingen, is shot during a siege. In order to keep his death hidden, Shingen, his brother Nobukado, and his most trusted generals agree to let a thief who’s sentenced to death impersonate him, in order to keep morale high, as he looks just like him.

In the beginning, the thief does nothing, as just his presence is enough. However, as time passes, he starts resembling Shingen, who has died in the meantime.

Akira Kurosawa proved that he had found himself with this film, a true epic that highlights the interaction of man with authority, and the cruelty and drama of war.

Tatsuya Nakadai gives another sublime performance in the double central role, in a film that won the Palme d’Or in 1980, among a plethora of other awards.

3. The Ballad of Narayama (Shohei Imamura, 1983)

Shohei Imamura combined two novels by Shichiro Fukazawa (the homonymous and “non-heir son in the family of Tohoku”) and created a film that won the Palme d’Or in 1983.

The story takes place in a secluded village in the mountains, about 100 years ago. Life in the area is very difficult, chiefly due to the cold climate and the lack of food, to the point that the inhabitants can taste white rice just once every year. These harsh conditions have led the people to live by a number of inhumane rules in order to survive.

In this cruelly pragmatist society lives Orin, the matriarch of the family, along with her widowed son, Tatsuhei, his children, and his brother Risuke. As she is 68 years old and has to abandon the village according to one of the rules, she tries to tie every loose end regarding her family.

Imamura directs a film that borders on being a documentary, due to the realistic depiction of life in the mountain villages of the country, a century before.

However, he retains his distinct style, as he includes many sex scenes, unexpected moments of humor, and a number of shots that could only be characterized as horrendously realistic.

Sumiko Sakamoto gives an astonishing performance as Orin, a very difficult character that can feel and show love and at the same time act in an utterly cruel fashion. Ken Ogata is also great as Tatsuhei.

2. Black Rain (Shohei Imamura, 1989)

Based on the homonymous novel by Masuji Ibuse, “Black Rain” was one of the most acclaimed Japanese films of the 80s, winning nine awards from the Japanese Academy and a plethora of others from festivals all over the world.

The film begins during the explosion of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima, as we watch three survivors, Mr. and Mrs. Shizuma and their niece Yasuko, walking through the streets while black rain showers them. Five years later, the three of them live together with Yasuko’s senile grandmother in a village with many survivors.

The Shizumas worry about the marriage prospects of their niece, since the fact that she may succumb to radiation sickness does not make her an appealing prospect. Yasuko does not share their worries and eventually befriends a veteran of war named Shuichi, who suffers from PTSD.

Shohei Imamura directs a social film regarding not the immediate victims of the atomic bomb, but the ones who suffer the consequences indirectly, as they become pariahs in society. He focuses on the relationships among them, and the fact that in order to cope, the previous generation clings to tradition while the new one is lost. In that fashion, he criticizes Japanese society.

The fact that radiation poisoning hangs like a Damoclean sword above their heads is a focal point of the film, as it shapes the character of everyone who was affected.

The film features magnificent black and white cinematography by Takashi Kawamata, while Yoshiko Tanaka as Yasuko gives a sublime performance.

1. Ran (Akira Kurosawa, 1985, Japan)

Kurosawa’s last epic was probably the most notorious entry in his vast filmography, since it was the most expensive Japanese film ever produced up to that point. It was also almost dropped for lack of funding, and the 75-year-old master lost his wife during the shoot, in an event that only stopped him for a day.

Eventually, and after many “skirmishes” with the Japanese film industry, it received Oscar nominations for art direction, cinematography, costume design (which it won), and Kurosawa’s direction, after a campaign started by Sidney Lumet. It is currently considered one of the greatest films ever made.

In feudal Japan, Lord Ichimonji decides to divide his realm among his three sons. However, after a misunderstanding with the younger son, he banishes him, in an act that eventually instigates a terrible war.

Kurosawa’s take on Shakespeare’s “King Lear” is a film focused on the bigotry and futility of authority, with a family resorting to war to win a throne. Furthermore, the film is an audio-visual masterpiece, with the scenery, the sets, and the battles being utterly magnificent. Kurosawa directs a tribute to the Jidaigeki genre, while presenting his critique of the history of Japan, through the chaos that seems to be the biggest driving force.

The film highlighted Kurosawa’s ability to direct and simultaneously shoot a large number of actors. This trait becomes particularly evident in the scene where Jiro launches an attack on Saburo’s forces, with the latter retreating into the woods. Kurosawa almost exclusively used long shots through many static cameras, cutting between them.

Author Bio: Panos Kotzathanasis is a film critic who focuses on the cinema of East Asia. He enjoys films from all genres, although he is a big fan of exploitation. You can follow him on Facebook or Twitter.