7. I Coulda Been a Contender – On The Waterfront (1954)

Monologues were the perfect weapon for a guy like Marlon Brando. The guy just chewed scenery up like bubblegum, and such charisma overflowed into this iconic scene from On The Waterfront (1954).

Tucked in a back seat with brother Charlie (Rod Steiger), the torn teamster takes off the dumb guy gloves and lets his sleazy sibling have it once and for all. Bitterness slips from every syllable in his slurred mouth, jabbering about forced dives in the boxing ring while glazing over Charlie’s half-hearted attempts to support him.

Even then, the tail end of Brando’s bitter edge morphs into that of a scared little brother, yearning only for the approval of his idol. “I coulda been a contender, I coulda been somebody” he famously proclaims, “instead of a bum, which is what I am.”

Shared glances weigh down the frame with regret, an accomplishment furthered by the pathetically sad “You were my brother Charlie, you shoulda looked out for me.” For all the political aspects of On The Waterfront, Elia Kazan’s emphasis on two little boys in the back seat was what truly stood the test of time.

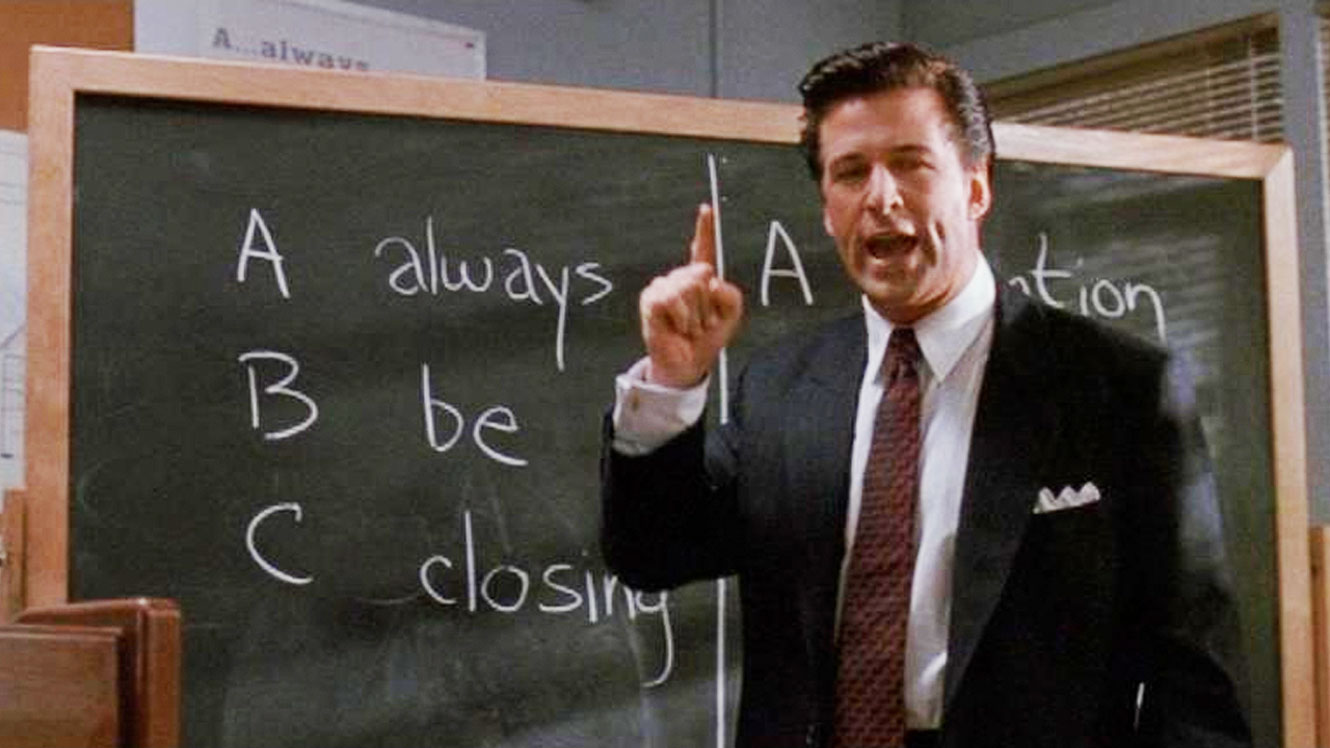

6. Always Be Closing – Glengarry Glen Ross (1992)

Morale gets taken to a whole new level with Glengarry Glen Ross, the 1992 drama that doubles as a clinic in onscreen acting. Working from a David Mamet script, the film portrays a sullen sales department struggling to stay afloat, whether they be mid-tier performers (Jack Lemmon, Alan Arkin), overwhelmed managers (Kevin Spacey), or hothead complainers (Ed Harris).

Such dire circumstance forces the hand of the higher ups, who send in Blake (Alec Baldwin) to rally the troops in the most verbally abusive manner imaginable.

Baldwin is a revelation in his brief performance. Wielding Mamet’s praised dialogue like a sharpened blade, he lays into each and every sap sitting before him with reckless glee. “The mediocre call be obsessed, the successful call me for advice,” he brags, before bouncing off tangents about his watch and the necessity of brass balls. “Coffee is for closers,” in Blake’s world, and this chest-puffing display is both mortifying and oddly inspiring all at once. “Have I got your attention, now?”

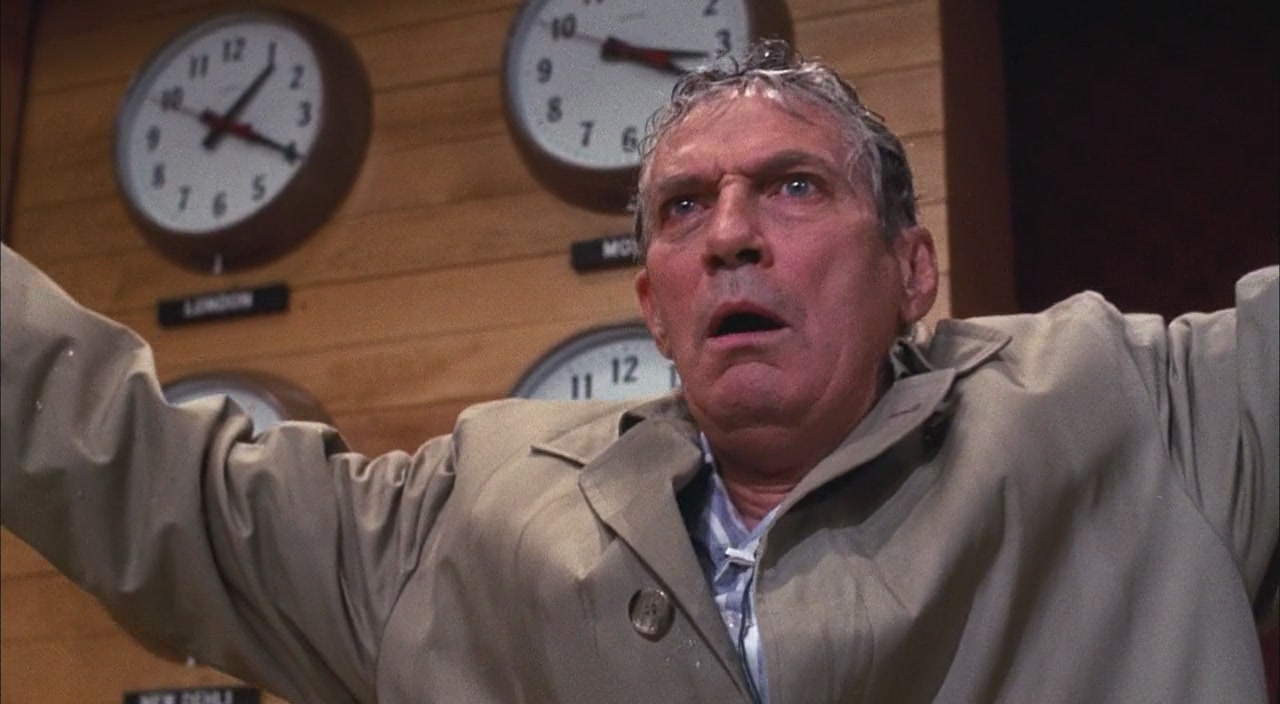

5. Mad As Hell – Network (1976)

So. Much. Anger. Granted, it’s obvious from the title, but Sidney Lumet’s scathing expose comes to a head with this awe-inspiring indictment of The American Dream. Delivered with the gusto of a man on the brink, this televised rant occurs after news anchor Howard Beale (Peter Finch) has been given two weeks notice on the air.

Penned by screenwriting savant Paddy Chayefsky, Beale’s tirade on the status quo in America is eerily prophetic given it’s 1976 timestamp. “The air is unfit to breathe and our food is unfit to eat,” the anchor snarls to his viewers at home, before rattling off violent crimes and homicides as if “that’s the way it’s supposed to be!”

Finch’s kooky delivery is made all the more frightening when realizing the validity in his words – a brainwashed nation content to relax while the powers that be play God. By the time Beale breaks into his signature “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take it anymore!,” Network hits a raw nerve that still needs healing today.

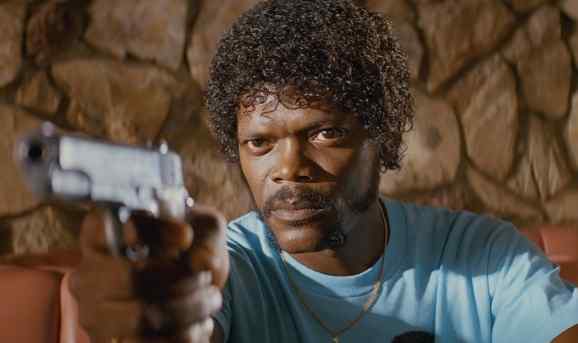

4. Ezekiel 25:17 – Pulp Fiction (1994)

Multiple monologues come up in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994). There’s Samuel L. Jackson’s Big Kahuna opener, or the Christopher Walken speech that’s undoubtedly made it’s way into multiple acting auditions in the decades since.

But beyond these stellar spots stands the film’s finale; a snarling nonlinear send off that has Jackson summing up the pithy attitude of Pulp’s living persona. Dressed like a dad at Disneyland and aiming his cannon at an unlucky Tim Roth, the Academy Award nominee lays into a verbal display both revealing and utterly cool in content.

Caught in a “transitional period,” Jackson’s Jules Winfield reserves the typical shootout for a chance to get some stuff off of his chest. Namely, Ezekiel 25:17, the (fictional) Bible passage that meant bad things for whomever was on the other side of his 9MM. But Winfield admits to never knowing what this passage truly meant until now, faced with the “tyranny of evil men” while trying to be the shepherd in a weak world. Both pimpish and profound, it’s the quintessential Tarantino moment.

3. Filibuster – Mr. Smith Goes To Washington (1939)

Many of the monologues on this list deal directly in the uglier side of mankind. As such, it’s refreshing to come across a speech as unabashedly hopeful as that of James Stewart in Mr. Smith Goes To Washington (1939).

Working for the second time with director Frank Capra, the gangly midwesterner takes upon the title role with reckless abandon, and nowhere is this charm more tangible than the filibuster finale of the film. Forced to hold the floor until his name is cleared of scandal, the unflappable Senator pours every ideal of American into his schpiel, down to reciting passages from the Constitution.

As hope dwindles and Smith becomes hoarse with despair, it is a final paean to lost causes that truly captures the route of the issue. In a world regularly susceptible to dishonesty, seeing one man, fictional or not, make a stand for integrity’s sake is downright inspiring. “Somebody will listen to me,” he barks out before collapsing on the committee floor. Seventy years later, people are still listening.

2. The Indianapolis – Jaws (1975)

Monologues like this materialize once in a lifetime. Originally penned by Howard Sackler, the salty account of The U.S.S. Indianapolis and its aftermath was spiced by screenwriter John Milius. A close friend of director Steven Spielberg, Milius infused a Hemingway-esque attitude that greatly benefited the character of Quint.

Consequently, three-quarters of a page transformed into a short stack speech, one that actor Robert Shaw requested to rewrite himself prior to shooting. The final product, a combination of three individual talents, comprise a scene that’s truly unforgettable to experience.

Shaw, gregarious as all get out and sporting a British brogue, tells the Indianapolis tale as if it were a horror story. Men stranded at sea, struggling to fend off sharks. “Sometimes the shark would go away, sometimes he wouldn’t go away,” he shares, before escalating to imagery far too tortuous to imagine.

Up to this point in the film, Quint is nothing more than an Ahab hardass, a sea-faring nihilist with a penchant for shark stabbing. But it is in this, his moment of verbal meditation, that the character (and his monologue) become movie myth.

1. Final Speech – The Great Dictator (1940)

Where does one even start with this speech? Charlie Chaplin, a man known for his devotion to silent cinema, wound up bestowing the artform with it’s most powerful deployment of dialogue to date. As the finale to his political opus The Great Dictator (1940), this impassioned broadcast comes from The Barber, a lowly worker mistaken for the Dictator of Tomainia: Adenoid Hynkel.

The Hitler parallels are obvious, right down to the sublime naming and stubble ‘stache that both men happened to share. Though it’s with this thinly veiled portrait that Chaplin tackles the impending horrors of The Third Reich with humanity’s greatest unifier: love.

It is simply sublime. “We think too much and feel too little,” he coarsely warns of modern man, before breaking into impassioned rants promising that “so long as men die, liberty will never perish.”

Chaplin, a veteran of the screen for over thirty years, had never uttered more than a few words, leaving this outpouring of ideology all the more shocking as a result. He would later claim that had he known the extent of Nazi evil at the time, he would have never made the film. Thankfully, he did, and the world will forever have these beautiful words to strive towards.

Author Bio: Danilo Castro is a freelance writer with a specialty in all things crime. But if it’s not, that’s okay too. Contributor to multiple publications and editor of the Film Noir Archive blog when he’s not watching movies.