14. The Front Line (South Korea)

To this day, the Korean War has not ended. No treaty or formal declaration has ever been signed. Instead, only an armistice has been signed, agreeing to a cease fire. Effectively, North Korea and South Korea are still at war with one another.

The Front Line depicts the final days of the conflict, as the UN brokered Armistice is being written up. Senior Officers on both sides hope to use the time to seize the Aerok Hills. Both sides have occupied the hill throughout the war, but with the armistice fast approaching, a win would not only secure a strategic victory for both sides, but would put several officers in favour with the government.

Just like Israel, many of South Korea’s filmmakers have served in the armed forces and with Seoul just 35 miles from the North Korean border, the realities of war are very real to the Korean public. Hence director Jang Hoon’s decision to examine the impact of the war on the Korean people, not just from physical or psychological level, but a spiritual one. Repressed memories and dreams are key to the film, a plea for the Korean people to never forget war and its consequences.

13. Waltz with Bashir (Israel)

Part documentary, part war film, part animation, Waltz with Bashir remains one of the most ambitious film projects of the twenty first century. Director Ari Folman, a veteran of the 1982 Lebanon War, is not making an informative documentary nor a ground breaking piece of experimental cinema, rather this is a soul searching exercise.

Plagued by bizarre dreams from his service during the war, Folman interviews many of his former squad mates when he realises he cannot remember anything about the war. As he digs into the past, slowly uncovering the truth, we are given a graphic display of his own subconscious.

Beautifully animated by Israeli Yoni Goodman, Waltz with Bashir is defined by the stark imagery of warfare. Ranging from the photo realistic to the symbolic, with images of soldiers emerging naked from the ocean to the ‘dance macabre’, a lone Israeli soldier firing a machine gun wildly, unable to control his stance, turning it into a almost beautiful waltz.

Ultimately uncovering his own accidently role in a massacre at a refugee camp, the film serves as a cathartic release not just for Folman but all veterans.

12. Downfall (German)

How exactly do you humanise one of the greatest monsters in history? Many, particularly Robert Carlyle (Hitler: The Rise of Evil), David Bamber (Valkyrie) and Noah Taylor (Max), have delivered haunting portrayals but nothing has come close to the contained and charming evil from Bruno Ganz.

Beginning ten days before Adolf Hitler’s death, the day Russian air strikes on Berlin ended and were promptly replaced with artillery. The Russians were no longer coming, they were here. Yet the Fuhrer is not worried. Instead he spends the day with architect Albert Speer, overseeing plans for Germania, the capital of the Reich.

Hitler even admits that the Russian attack could be a blessing in disguise, remarking that the Russian bombardment will remove the old Berlin. Even in his final days, Hitler believed that there was still a chance of victory.

The audience becomes a fly on the wall as key members of the German Government come to the slow realisation that the ‘Thousand Year Reich’ is coming to an end.

The most chilling is Hitler’s realisation in the bunker that Steiner’s Detachment exists only on paper, leading to a meltdown that created a YouTube meme. Robert McKee states that if we want to find true character, put that character under great stress. Plenty of stress to be found for key members of the Nazi Party as the Soviets exact their revenge.

Ultimately we gain an insight into the figure heads of Nazi Germany, revealing a human side, making us wonder whether they would take responsibility for their actions. A curiosity quickly dismissed with mass suicides ensuring their last act of defiance was to deny the world justice.

11. Brotherhood of War (South Korea)

For the rest of the world, the Korean War was a proxy war. Just another theatre of conflict for the Cold War, an attempt to stop the influence of Communism in Asia. For Koreans, it was a civil war. The concept of brother fighting brother was very real. Families would divide their families, sending half to the other Korea. They believed that if the impending war would destroy one Korea, they could save the family name by dividing it half.

The themes of brotherhood is personified by the Lee brothers. Older brother Jin-tae owns a shoeshine stand, raising money to send his younger brother, Jin-seok, to school. When North Korea invades in 1950, both brothers find themselves conscripted in the Army, witnessing history including the occupation of Pyongyang and the Chinese invasion.

Ultimately, the brothers end up on opposite side but their conflict is dwarfed by the betrayals and political strife evident in society. Returning home after fighting against the evil of a totalitarian government and its military, the brothers witness civilians being rounded up and executed by the far-right secret police. Brothers killing brothers. Despite the violence, the film offers a touching moment at its conclusion, one offering redemption and reconciliation.

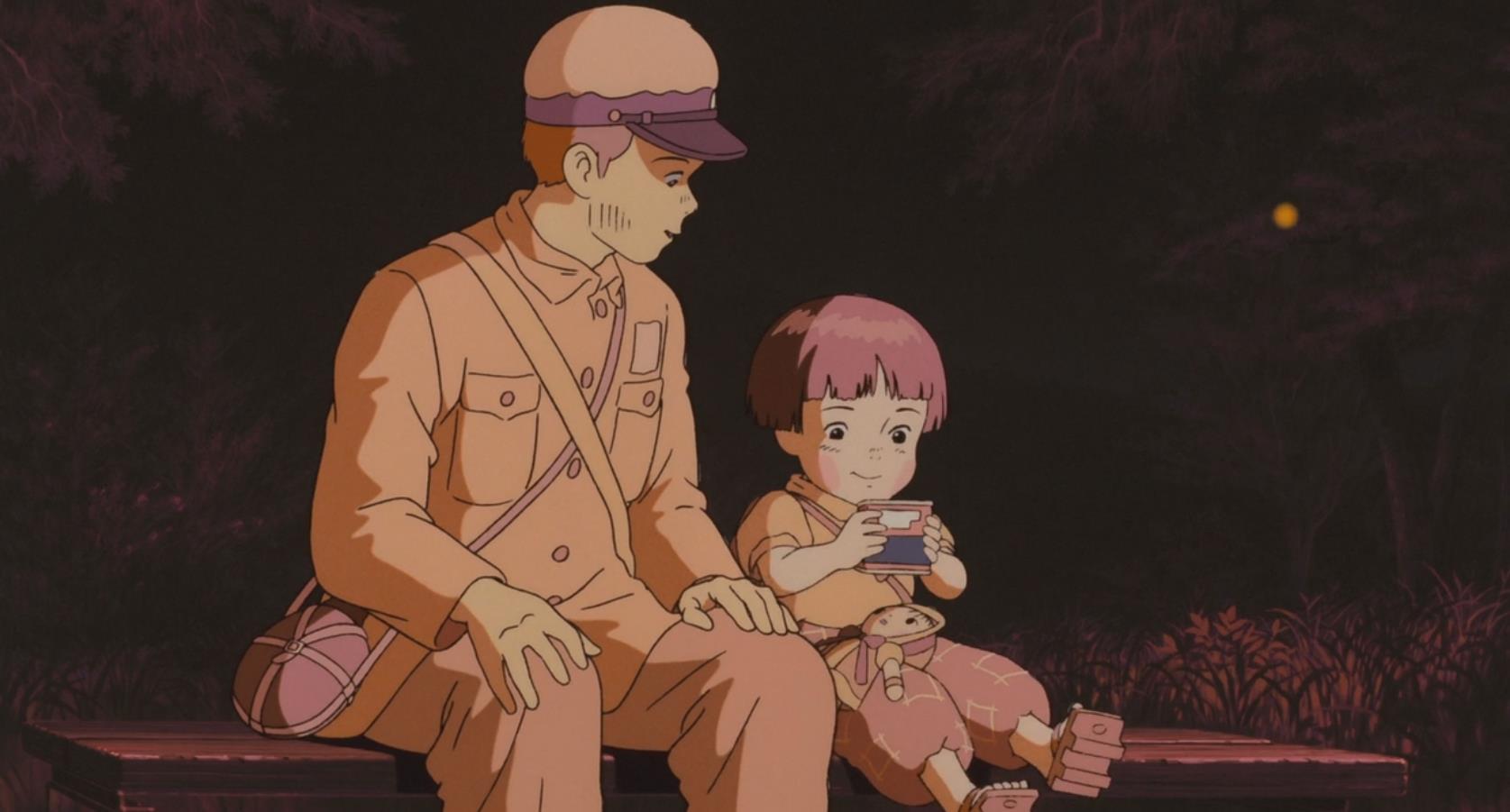

10. Grave of the Fireflies (Japan)

Like Germany, Japan holds a large amount of shame and guilt for its involvement in the Second World War. Its national subconscious still scared from such a heavy defeat at the hands of the Allies, culminating in the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The war has generally been a topic avoided by Japanese filmmakers, however, bubbling under the surface is a anti-war spirituality, similar to South Korean cinema.

Based on the semi-autobiographical short story by Akiyuki Nosaka, based on his own experiences with the Allied firebombing of Kobe in March 1945, the film follows Seita, a Japanese youth living in post-war Kobe.

Children in war has always been a hot topic for filmmakers, adding a fresh perspective to familiar stories. Films such The Book Thief, Hope and Glory and Empire of the Sun have explored warfare from the innocent eyes of children, just like Grave of the Fireflies.

While two live action remakes have since been produced, Isao Takahata’s original 1988 animation remains one of the most beautiful yet haunting renditions of war. An animation style that many associate with the works of Hayao Miyazaki (Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle) is used here to illustrate disease, faming, suffering, dying and war.

Yet Takahata, like Terence Malick with The Thin Red Line, is able to find the beauty in war through nature, the rare glimpses of wonder that only a child could see in war.

9. Das Boot (Germany)

With the Swastika flying over Paris, Germany had finally captured the one thing that had caused its defeat during the First World War: access to the Atlantic Ocean. With Great Britain relying on supplies and troops from the United States and Canada, the Atlantic became open season as Germany’s feared U-Boats were targeting everything.

For decades, cinema has portrayed the thrills of submarine warfare, seen with U-571, Crimson Tide and The Hunt for Red October. However, what was missing was the claustrophobia, the anxiety, the loneliness and of course the human interactions with the submarine.

The cramped conditions, the smells, the heat and cold and the creaks and groans of a hollow metal tube that may just pop. There is no secret mission or call to arms that could change the war, this is just another patrol.

Director Wolfgang Peterson achieved a career high with the film (including 2 Oscar nominations) and, despite a strong career in Hollywood, never topped this achievement. Das Boot remains a haunting reminder that millions of Germans died during the war, some of them left at the bottom of the Atlantic ocean suffering a fate dreaded by every soldier: to be forgotten.

8. Rome, Open City (Italy)

Much emerged at the conclusion of World War II: new nations, new governments, new technology. Art also changed in many forms, including new forms of cinema including one of the most influential styles: Italian Neo-Realism. With the world recovering from war, audiences no longer accepted old Hollywood melodramas, mostly shot on studio lots and sound stages. Instead, they wanted films from the real world. Films with real locations, real characters, real stories.

By 1944, Director Roberto Rossellini was essentially holding up the Italian film industry with his own two hands. The country was divided with the Germans occupying the north and the Allies the south and the country was on the verge of civil war. Out of this chaos, Italian Neorealism was born, focusing on social issues like poverty, politics, war, oppression and injustice.

Rome, Open City was one of the first to experiment with this style, perfectly illustrating its key themes with the story of a Communist resistance fighter struggling against the Nazis during the German occupation of Rome in 1943.

Many of Rossellini’s cinematic techniques, including moving cameras and non-professional actors, have since been utilised by classic war films including Apocalypse Now, The Deer Hunter and Saving Private Ryan.