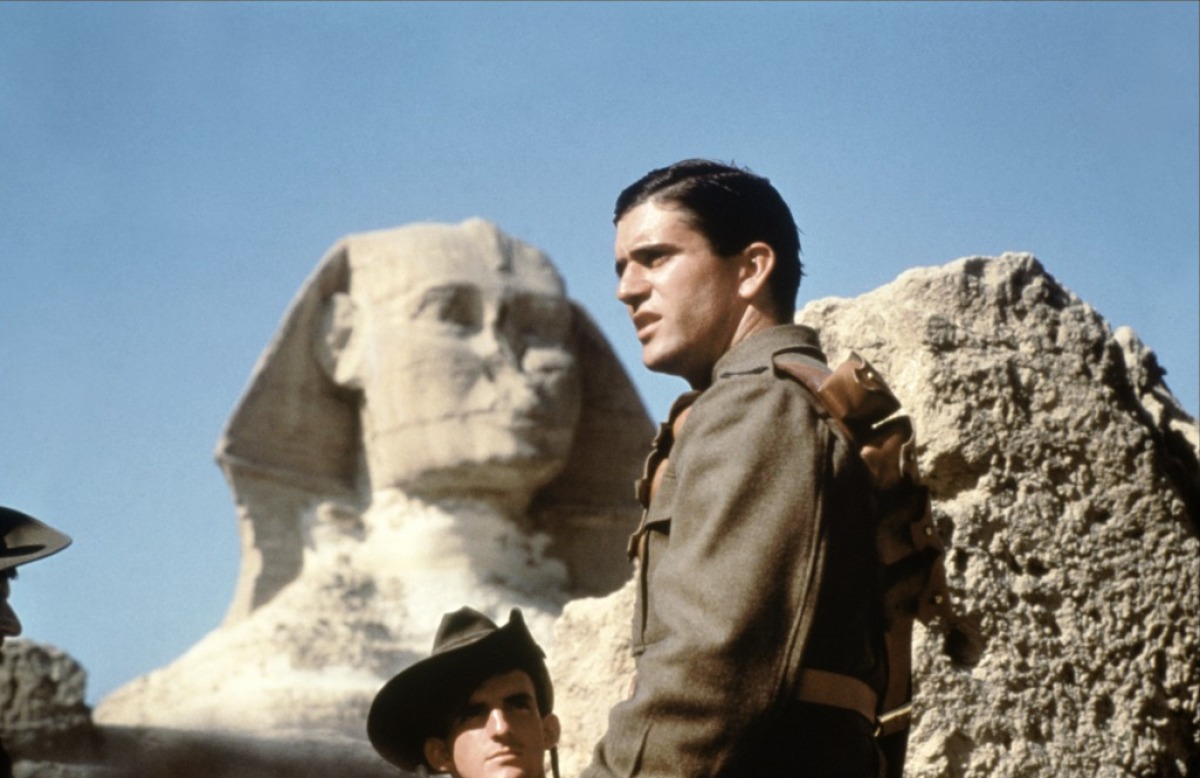

7. Gallipoli (Australia)

For many Australians, the birth of their national pride occurred on the 25 April 1915, during the Allied invasion of Gallipoli. Initially, the invasion was planned as a lightning strike against the fledging Ottoman Empire, hoping to seize the capital of Constantinople in a matter of weeks. Unfortunately, poor planning, bad whether, bad luck and strong resistance from the Ottomans led to a disaster.

For director Peter Weir, who later went on to Hollywood glory with Witness, Dead Poet’s Society, The Truman Show and Master and Commander, the film is less about the war and more about the theme of mateship.

Mateship plays a large part in Australian society and with the myth building that occurred after the war. We do not actually see battle until over half way into the film. Instead the film is about the friendship between two men both travelling across the Western Australian desert to enlist.

Ultimately, the film is an exploration of Australian society. A blinding loyalty to the British, an obsession with sports, a mischievous nature and the endearing spirit of mateship. It is hard to forget this in the final moments when the Light Horse are given the order to charge.

Despite obvious death, they remove their bayonets (their only weapon), using them to pin their belongings into the trenches. They knew they would die, but they would not die alone.

Archie, a natural sprinter who could have gone to the Olympics, makes it the farthest before being gunned down like the all the rest. The film pausing at the moment of his death. Just like Robert Capa’s The Falling Soldier, the film immortalises the fallen.

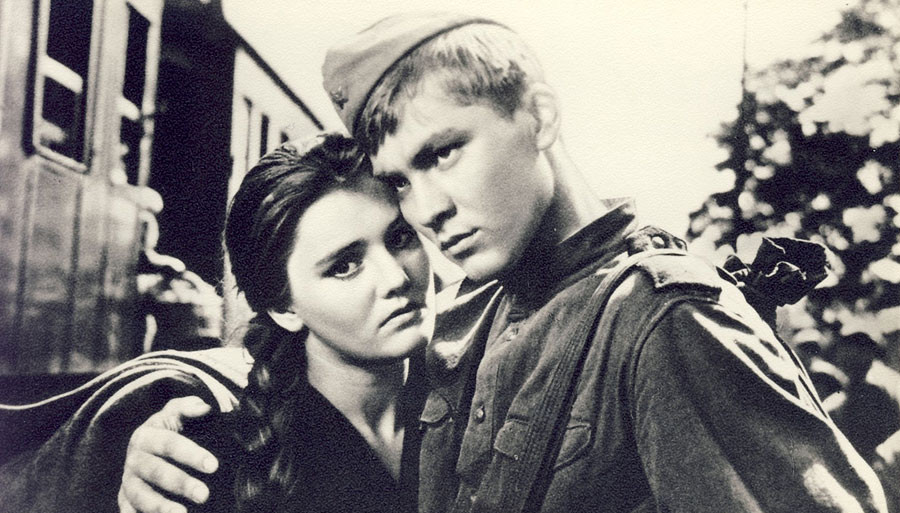

6. Ballad of a Soldier (Russia)

The death of Stalin in 1956 opened the Soviet Union to many more freedoms under new premier Nikita Khrushchev, clearly seen in the expansion of its film industry. Originally, Soviet films contained messages and themes that were in line with Soviet policy, seen with Alexander Nevsky’s anti-Catholic, anti-Fascist and anti-Bourgeois sensibilities. Ballad of a Soldier is different.

After single handedly destroying two Nazi tanks on the Eastern Front, teenage soldier Alyosha requests leave to return home and fix his mother’s roof instead of accolades and medals. Along the way, he meets an array of characters and even falls in love. Ultimately, the film is a tragedy.

While it does not criticise the war, it laments over the millions of men and women killed fighting in the war. We learn from the beginning that Alyosha would eventually die in the war, denied the opportunity to return home and marry the girl he loves. Even his act of great courage, destroying two tanks, was done out of self preservation, not courage.

Ballad of a Soldier was one of the first Soviet films to transcend the barrier between East and West. The film was screened at Cannes and even premiered in the United States, where it was nominated for an Academy Award for its screenplay.

5. Life is Beautiful (Italy)

So far, writer/director/Roberto Benigni has been unable to follow up the success of his 1997 classic Life if Beautiful. While technically a romantic comedy, the film is set prior and during World War II and takes a unique perspective on one of the worst crimes committed against humanity.

What makes Life is Beautiful so unique is the way Benigni’s character, Guido, rebels against the Fascists by protecting his son’s innocence. Despite dealing with escalating anti-Semitism in Italy prior to the war, Guido always maintained a dignified sense of humour about it.

One would think that would disappear with his incarceration in a Nazi Concentration Camp. However, with his young son present, Guido goes to extreme lengths to protect his son from the horrors of a concentration camp, telling his son that their incarceration is really just part of a big game where the prize is a real battle tank.

Throughout the ordeal, his son remains oblivious to the dangers around him, all thanks to his fathers efforts. Even as Guido is marched by the SS to be shot, he performs a humorous march in order to amuse his son. Ultimately, Guido performs the ultimate act of defiance. He gave his life, but they could not take his son’s innocence.

4. The Pianist (France & Poland & Germany & UK)

Roman Polanski’s Academy Award win for Best Director was highly controversial in 2004. After all, the Polish-French director could not even attend the ceremony as he is still a fugitive, wanted by the United States government. Regardless of your opinions on the man, it is impossible to deny his skill as a filmmaker.

Polanski, a Holocaust survivor himself, clearly holds this story close to his heart, able to relate to it in so many ways. Wladyslaw Szpilman (Adrien Brody in a career best) is truly the same as Polanski.

Both were fragile artists, plunged into the middle of a great evil. When his family is transported to Treblinka, a sympathetic guard smuggles him out, leading Szpilman to spend the remainder of the war in Warsaw where he witnessed the Ghetto Uprising.

The Pianist may be a humane portrait of survival and the human spirit, but it is also a ode to the power of art. Szpilman’s life is saved twice, once by the guard and a second time by a Wehrmacht officer who supplied him with food and clothing during the final months of the war. Both sympathetic due to his skills as pianist.

3. The Battle of Algiers (Italy & Algeria)

Despite victory during the Second World War, stability did not return to the newly formed French Republic. The source of much of its pain was not in the homeland, but rather across the Mediterranean in Algeria.

Arab Nationalists began to rebel against the French government leading to protests, crackdowns, rebellion and eventually civil war. The war threatened to tear France apart as Algerian based Pied Noirs and the French Military planned an airborne assault on Paris to remove Charles De Gaulle from the presidency.

Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo plunges the audience right into the depths of the Algerians guerrilla warfare against the French. Utilising Italian Neo-Realism and a documentary/news reel style, Pontecorvo achieves a first in filmmaking: a film that makes the audience feel like a participant rather than just a witness.

Pontecorvo does not just achieve this through his visuals but also his politics. The film attempts to be neutral, reminding the audience that the French soldiers, who were accused of being Fascists by the rest of the world, fought against the Nazis either with the Free French or the resistance.

2. Come and See (Russia)

One of the most chilling, horrific and haunting war films ever committed to the screen. Director Elem Klimov never made another film after Come and See, stating that he had nothing left to say. With a final film like this, he does not have to.

Set in the Byelorussian Soviet Republic (modern day Belarus), the film follows Flyora, a young villager, who digs up a old Russian rifle and proceeds to join the Partisans (local resistance). Soon separated from the main force, Flyora goes on a journey through the country where he eventually witnesses the true horrors of war.

The film is not outright violent, infact hardly any violence occurs on screen. Rather there are simply glimpses of violence. The brief shot of the bodies in Flyora’s village will shock you right to the core but the true horror comes in the final scenes where he witness the real evils of war as the SS burn down a hut filled with civilians, laughter and joy spread across their faces as they drag a young girl off to be raped.

In the end, the horror is not conveyed through violence or blood or gore, rather it is through the eyes. The film’s most memorable shot (seen on the poster) is when Flyora is posing with three Germans, one of whom is pointing a Luger at his head for a photo, a look of sheer horror and torment in the eyes that makes you wonder how much of it is acting and how much is real. This is a film that will stay with you for a long time.

1. La Grande Illusion (France)

Arguably one of the finest films ever made. Jean Renoir’s classic is considered a master piece in French cinema and is one of the most influential war films of all time.

When two French aviators, one aristocratic and one working class, are shot down, the pair are taken to a Prisoner of War camp where they plot an escape despite the aristocratic officers new found friendship with a fellow German of royalty. For Renoir, the film is plea for common humanity.

Within a year of its release, Hitler had annexed both Austria and Czechoslovakia and within a year of that, he ordered the invasion of Poland, triggering World War II. The writing was on the wall for this and the film targets the nationalism of its various audiences, reminding them that despite their differences, they still share a common humanity.

While the film’s message was ignored so soon after, it remains one of the most beautiful artefacts from pre-war cinema, a testament to the hope and compassion that was starting to emerge in Western Europe and would lead to a unified continent within half a century.

Author Bio: Jack is currently studying a Master of Arts in Creative Writing at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS). He enjoys binge watching films, writing scripts that may never be made and hopes to find the courage to start his film blog.