7. Shame (1988)

Steve Jodrell’s look at the modern outback town is vicious and unforgiving. A western crime thriller on one hand and an action road movie on the other, ‘Shame’ helped expose one of the dark, vulgar secrets silently festering at the heart of Australia.

A barrister (Deborra-Lee Furness) who breaks down in a rural town in Western Australia comes under attack when she stays with a girl (Simone Buchanan) who has been gang-raped by a group of unconvicted youths.

‘Shame’ in many ways is an Australian, feminist equivalent of ‘In the Heat of the Night’. Both feature a crime in a small, rural town and a hero who must work to achieve justice against a prejudiced population and police-force. Whereas Norman Jewison’s excellent mystery had an optimistic conclusion however, the ending to ‘Shame’ is tragic.

It concludes that no individual, no matter how strong, courageous or intelligent, can eliminate an unspoken evil which society wilfully choses to tolerate. Misogyny is painted as a pervasive foe. The crime is unseen, shown only in the silent gazes of the locals, and dismissed quickly in the presence of the town’s police sergeant and even the victim’s father.

‘Shame’ masterfully constructs the outback as a wilderness which is still feral, a place where a very different kind of monster now reigns.

6. Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981)

George Miller’s second ‘Mad Max’ film is probably the most iconic, the most watched and the most influential Australian film ever made. Dark, thrilling, stylish, eccentric and visionary ‘The Road Warrior’ revolutionised the action film genre and conclusively defined the Australian outback as a strange, mythical place of darkness and desperation.

The typical Western blueprint is placed in a nuclear wasteland: the titular hero (Mel Gibson) rediscovers his humanity when he helps a small community escape a nomadic gang of marauders.

Aside from the ground-breaking action sequences and car chases – each one amongst the best ever filmed – ‘Mad Max 2’ is perhaps most noteworthy for its costume and production design. It’s a steam-punk western set in a place lost in time: a deformed mix of medieval armour and mechanical beasts.

The quirky, anarchic world of ‘The Road Warrior’ doesn’t quite feel historical, prophetic or even allegorical. It’s one of the most unique gothic films ever made: a Byronic hero travels in a motorized dragon across an impossible world of dark and light, evil and myth.

This vision of a legendary world in the heart of Australia came to define the nation’s image for decades to come. It’s no exaggeration to call ‘Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior’ one of the most important films ever made; it’s an absolute must-see for any cinephile.

5. The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978)

Bizarrely, Fred Schepisi’s historical drama is one of Australia’s most notorious yet inaccessible films. Violent, difficult and surprisingly true to its time period, ‘The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith’ makes to be one of the most unforgettable of all Australian films.

Based on the novel by Thomas Keneally and inspired by the life of the real bushranger Jimmy Governor, it follows an Aboriginal man (Tom E. Lewis) who, after a life of exploitation and systematic abuse, finally lashes out violently.

The enthusiasm on the hardworking Jimmie’s face is slowly stamped out (performed brilliantly by Lewis in his first major role). The music goes from mournful tune to a building beat of bubbling rage. The violence which thus follows is no coherent act of war; Jimmie has become the mad dog which white society has treated him as.

The turning point is one of the most shocking moments in any film: a group of women are brutally axe-murdered in their own home. Arterial blood sprays over virginal white.

Inevitably the film retreats to the stark, rocky landscape which, like the murders’ face, stays calm and indifferent as the blood s. It’s clear that the genocides attempted by both white and black are motivated not by any logical or moral reasoning but by nature and circumstance; all mercy has been forgotten.

‘The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith’ depicts a place which is at war with itself, where the distinction between black and white, good and evil, and the pure and the corrupted slowly fades away. It’s an unsettling tragedy which leaves neither heart nor body nor soul intact.

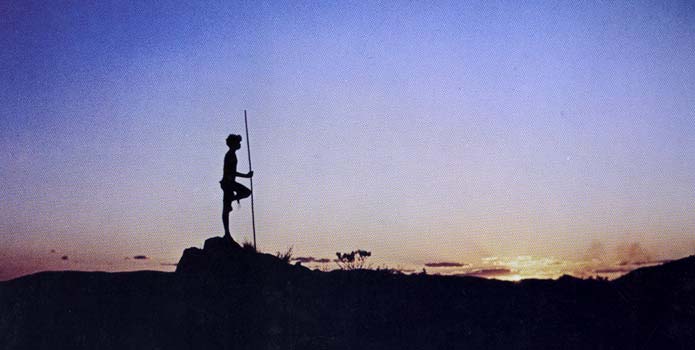

4. Walkabout (1971)

Auteur Nicholas Roeg was not Australian, and yet his coming-of-age adventure ‘Walkabout’ is one of the finest and most authentic Australian films ever made. Like Roeg’s other works, it’s a poignant, dreamish journey which skilfully evades any straightforward or linear explanation.

After becoming lost and stranded in the outback, a sister (Jenny Agutter) and brother (Lucien John) meet an Aborigine (David Gulpilil) on walkabout.

In Roeg’s trademark style, the film is tied together visually, eerily drifting from frame to frame, repeating the same pan or zoom, often regardless of whether the shots logically precede one another.

There’s a stark contrast between sand and sky, predator and prey, black and white, life and death, spiritual and real, masculinity and femineity, sexuality and abstinence, freedom and repression, supernatural and scientific, and chaos and order.

In the outback there is no middle ground between these warring forces. As such, the tensions which Roeg establishes, sexual or otherwise, are never actually resolved.

Spellbinding, lonely and passionate, ‘Walkabout’ masterfully compares the intricate landscape of a country to the intricate landscape of the human soul.

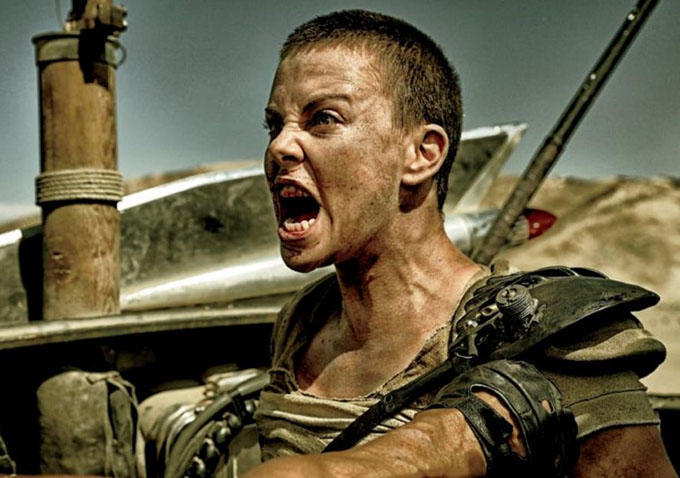

3. Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

Is ‘Fury Road’ the best ‘Mad Max’ film? Managing to expand the universe’s scale in terms of landscape, theme, character and action without losing any of its vicious spirit, while also offering a welcome, long-overdue twist on the masculine-driven action film, George Miller’s most recent outing certainly seems the most impressive.

In the post-apocalyptic wasteland, Imperator Furiosa (Charlize Theron) enlists the help of the drifter Max (this time played by Tom Hardy) when she rebels against a tyrannical patriarch (Hugh Keays-Byrne).

Stylistically ‘Fury Road’ retains the same extravagance that the originals possessed yet outrageously ups the ante: cars are thrown around hellishly in a dust storm, pale soldiers jump from car to car, and a chained guitarist in a gimp suit shoots flames off a truck.

While it wasn’t actually filmed in Australia, the landscape of ‘Fury Road’ perfectly embodies the Outback Gothic tradition. It’s an industrial wasteland, reflecting the loneliness, savagery and absurdity of the human mind, and is characterised by a sharp contrast between man and woman, survival and extinction, war and peace, barbarism and civilisation, home and homelessness, autocracy and anarchy, and darkness and light.

‘Fury Road’ neither replaces nor overshadows the originals, rather it stands shoulder to shoulder with such classics as ‘The Road Warrior’ as one of the very best action films of all time.

2. Wake in Fright (1971)

‘Wake in Fright’ is one of only two films ever to be screened twice at Cannes. Returning from apparent oblivion only a few years ago, Tod Kotcheff’s outback tale is still one of the most nightmarish films ever made, lingering under the skin in a way which feels all-too-real.

A young schoolteacher (Gary Bond) slides deeper and deeper into darkness after becoming stranded in an ominous outback town.

Is it a horror film? ‘Wake in Fright’ contains no evil monster, no clear-cut villain and no supernatural causation. But it’s for that very reason that it’s so terrifying; all the horror which occurs is so realistic and honest that anyone could experience it; in fact, everyone probably has.

The evil is virtually unspoken: glasses upon glasses are filled with beer, drunkards cheer and chant in a deafening barrage of bank notes and gambling chips, and injured kangaroos hop around desperately in the swirling night (the hunting footage which was not faked).

‘Wake in Fright’ captures the sensation of being in a literal hell. Drunkenness, gambling, debauchery, killing and, eventually, madness takes hold. Visions of a couple copulating and of chips flying onto a man’s eyes like Charon’s obols flicker nightmarishly as our anti-hero flees fruitlessly through the boiling waste. There’s no escape; hell invades his very soul.

‘Wake in Fright’ is one of the great experiential films; it’s terrifying, disquieting and magnetic, and needs to be seen to be believed.

1. Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975)

Peter Weir’s faithful adaption of Joan Lindsey’s ‘Picnic at Hanging Rock’ is the perfect Outback Gothic: eerie, magical, enigmatic and seductive.

On St Valentine’s Day, 1902, three girls and a teacher disappear without a trace while on a picnic in the outback.

The dreamish pans, whimsical girls and electrical hums resemble the quaint and ghostly passage of a memory. Set a year after Federation, ‘Picnic at Hanging Rock’ cautions that Australian society is founded upon a bizarre agreement with the bush that can fracture at any moment.

The girls’ virgin white, puritan dresses are packed against the vastness of the bush. As each item is removed, first the gloves and then the stockings and corsets, civilisation sinks further and further into the pervasive force of the bush.

It’s more than just a warning of the dark allure of the outback. Weir forces his white Australian and male audience to realise that as Europeans they know very little of the supposedly-conquered Australian landscape, as males know very little of the female mind, and as humans know very little of the world around them.

‘Picnic at Hanging Rock’ is one of the best gothic films ever made. Ultimately we have to accept any perverse scenario we conjure up as our own; we come to realise that humanity’s darkest secrets are neither uttered nor heard, but confined in the unseen orifices of the eponymous Hanging Rock, the unseen orifices of the human soul.

Honourable Mentions:

Other Outback Gothic films worth your time include: Sunday Too Far Away (1975), The Last Wave (1977), Mad Max (1979), My Brilliant Career (1979), Road Games (1981), Rabbit-Proof Fence (2002), Japanese Story (2003), Jindabyne (2006), Rouge (2007), Beautiful Kate (2009), Bran Nue Dae (2009), Sampson and Delilah (2009), Tracks (2013), The Rover (2014) and Wyrmwood: Road of the Dead (2014).

Outside of the “Outback Gothic”, Australia has also offered countless great urban and suburban gothic films including Patrick (1979), Romper Stomper (1992) and The Babadook (2014).

New Zealand has a gothic genre akin to the “Outback gothic”, which similarly focuses on sharp contrasts between civilisation and nature, black and white, magic and reality and man and woman. Its masterpieces include The Piano (1993) and Heavenly Creatures (1994).

Author Bio: Kyle McDonnell is an aspiring filmmaker based in Sydney, Australia. He recently graduated from high school and hopes one day to emulate his screen heroes David Lynch and Ben Wheatley. When he’s not watching, writing or filming, he can be found listening to ‘The Smiths’, contemplating life.