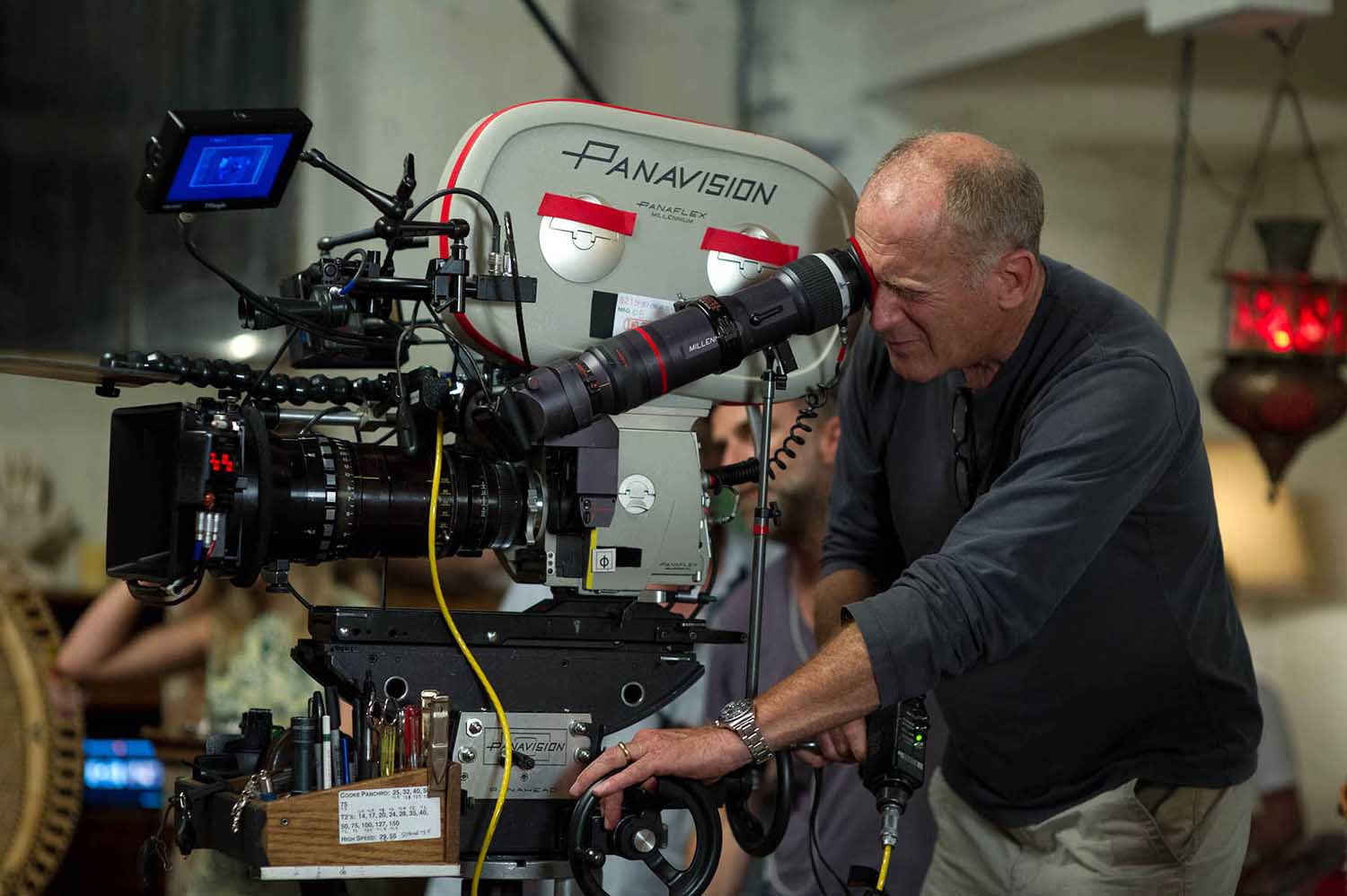

7. Robert Elswit

Robert Elswit is, probably, the best cinematographer working today in film. He is a tireless supporter of filming on film and not of using modern digital technologies. In his opinion, film gives to the director and the cinematographer much more artistic freedom than the (at this point) normal digital medium.

And when we see his work in “The Master” (or in every other Paul Thomas Anderson movie, from “Punch-Drunk Love” to “There Will Be Blood”), we can do nothing but agree with him.

Signature film: “The Master”, directed by Paul Thomas Anderson

Elswit’s work here is astonishing, even more than the multi-award-winning “There Will Be Blood”. Every scene has something going on, and every frame is particular and even strange to our conception (also thanks to Anderson’s great talent). Even the handrail of a ship becomes something new and unseen.

The genius of Elswit and Anderson is in the little things; small and maybe unimportant scenes are more remarkable than the main ones (in the mind of the spectator, the first dialogue between Joaquin Phoenix and Hoffman is more likely to remain than the motorcycle drive). It may be a masterpiece and a magnificent cinematography work.

6. Robert Yeoman

Like most of the cinematographers on this list, Yeoman gave and continues to give his best work by collaborating with a specific director. In this case, we are talking about Wes Anderson. There are some who still persist in hating this amazing director, who can perfectly fuse together magical and deep stories with a compelling vision of reality. And to reach this effect, Yeoman is fundamental.

Signature film: “The Grand Budapest Hotel”, directed by Wes Anderson

Even if Anderson’s best movie is still “Moonrise Kingdom”, “The Grand Budapest Hotel” summarizes and contains all the elements of his cinema, from the pastel colors to the wide angles and the horizontal tracking shots. Visually, it is, without any doubt, his most compelling and astonishing movie and Yeoman’s best work yet.

5. Janusz Kaminski

Kaminski entered into Steven Spielberg’s filmography at the beginning of the 1990s, in the part of his career characterized by great movies, but also by bad delusions and missed occasions. Nevertheless, since then, Kaminski has given Spielberg something more; something that made his films the great movies we all now remember.

Signature film: “Schindler’s List”, directed by Steven Spielberg

Kaminski supports Spielberg’s choice of filming the movie as if it was a documentary by choosing a perfect and disquieting lighting, which can be easily associated with the photography of German Expressionism. It is a work on the (absence of) color that has no equal in modern times.

4. John Toll

Two-time Oscar-winning cinematographer John Toll did not just make good movies. He photographed good films like “Braveheart” and “The Last Samurai”, but also mediocre cine-comic films like “Iron Man 3”, in which an authorial touch is really difficult to see.

Besides, at the end of the 90s, he realized his (and its director’s) masterpiece by photographing the landscape perfectly, as he did also in the aforementioned movies, giving the nature a personal and actual living soul.

Signature film: “The Thin Red Line”, directed by Terrence Malick

In his best film, Malick demonstrates to us the total superiority of nature above humankind, and its fair indifference for human vicissitudes and wars.

To achieve this aim, Toll was able to shoot nature as something superior, but not terrifying or intimidating, just closer to God (whoever or whatever it is) than it is to us common mortals. And, incredible but true, Malick and Toll literally shot the wind. Just for this movie, Toll could not have been left off this list.

3. Robert Richardson

In an antithesis to Cronenweth, Richardson is, like Elswit, a strenuous supporter of shooting on film. Because of that, he is Quentin Tarantino’s go-to cinematographer after having worked with many great directors, such as Oliver Stone (“JFK” and “Natural Born Killers” are almost masterpieces) and Martin Scorsese (“The Aviator”, “Hugo”).

Signature film: “The Hateful Eight”, directed by Quentin Tarantino

Tarantino’s last underrated movie is Richardson’s best work because of the challenge that filming in 70mm brings. Yet, the result is astonishing: if the 70mm film has been used to shoot landscapes and the imposingness of nature/court/battle in the past, in “The Hateful Eight” the usage is completely different and almost the opposite.

In fact, the majority of the movie is set in a haberdashery, and it is composed of just a bunch of people talking. The 70mm film gives Richardson the possibility to include in the frame almost every character present, in a use of the depth of field rare in these years.

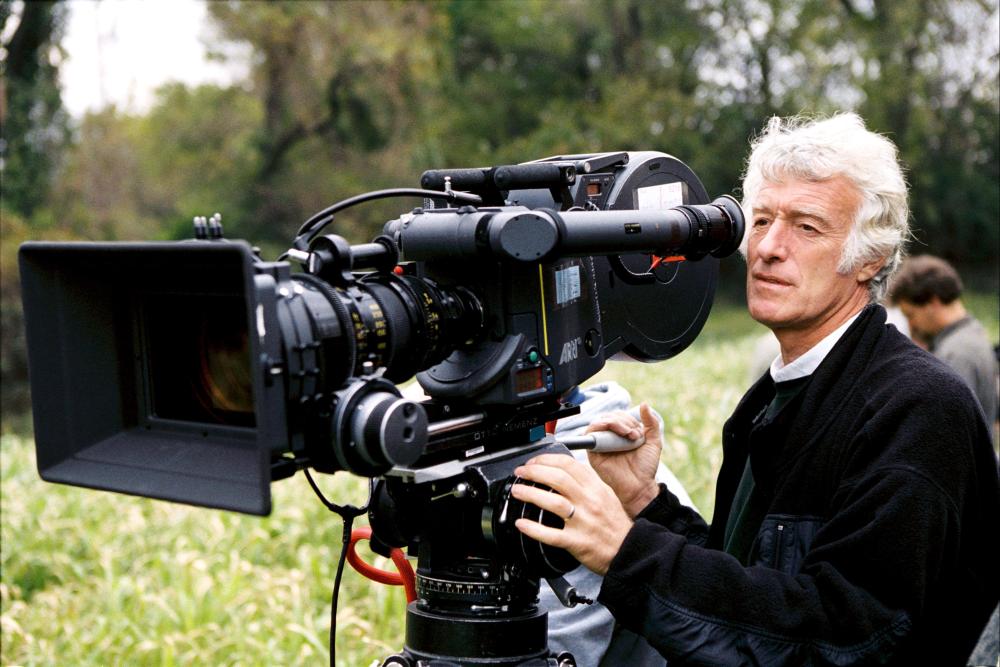

2. Roger Deakins

The fact that Roger Deakins has not won yet an Academy Award is more serious than DiCaprio’s many losses. Deakins has worked with many great directors, such as Coen Brothers (“O Brother, Where Art Thou?” and “The Man Who Wasn’t There” are amazing) and M. Night Shyamalan (the forest of “The Village” is hard to forget), but his recent collaboration with Denis Villeneuve contributed to the unleashing of his genius.

Signature film: “Sicario”, directed by Denis Villeneuve

In this excellent movie, Deakins emanates all his visual talent through every frame. He makes the landscapes look closed-off and claustrophobic, just like the marvelous sequence in the tunnel. Every scene is photographed perfectly, and every frame could be literally framed.

1. Emaneul Lubezki

Praised by both critics and the public, Emanuel Lubezki works with lighting (sometimes natural), focus, film and digital, excelling in everything. Almost every movie he worked on has a poignant cinematography, from “Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events” to “Burn After Reading”, passing through “Sleepy Hollow” and “The New World”. The winner of two Academy Awards, Lubezki can easily win another one this year with his most recent masterpiece.

Signature film: “The Revenant”, directed by Alejandro G. Inarritu

Maybe it is not the revolutionary cinema milestone a lot of people are screaming about, but it surely has one of the best visual impacts and cinematography ever seen on film. It’s not just because the natural lighting, but also because of the total immersion the spectator feels watching these astonishing landscapes and these long takes. And the real main character is not Inarritu’s direction, but, without a doubt, Lubezki’s cinematography, in one of the best ever made.

Author Bio: Pietro Mauri lives and studies in Milan, Italy. He collaborates with some Italian movie websites. He writes about cinema because he says, paraphrasing Ingmar Bergman “Cinema is a need, like eating, drinking or sleeping, and every cell in my body is completely imbued with it”.