8. Revolt of the Fishermen (1934). Dir. by Erwin Piscator.

Piscator’s influence on cinema and theatre still resonates today, from his early work with Berthold Brecht to him founding the Dramatic Workshop in Manhattan, thus forever changing the way actors are taught and how they act. The list of his students runs as a Who’s Who-Marlon Brando and Harry Belafonte, Ben Gazzara and Eli Wallach, Walter Matthau and Tennessee Williams.

In between rocking the German theatre and transfiguring the American, he made a brief sojourn to Soviet Union, having to flee Germany when Nazis were gaining power and leftists like himself were in increasing danger. There, he made his only film. The content is typically commie-oppressed fishermen go on strike, heartless bosses bring in scabs, workers fight back, with bloody and heroic results. What makes it stand out is the execution.

Being a theatre man and inexperienced in cinema, Piscator successfully “borrowed” the most distinct cinematic techniques of the time-German Expressionism and Soviet Montage. The distorted cinematography, low angles, dim lighting, an alliance of gloomy sailor and an earthy whore-those elements bring Lang, Murnau, and Paul Leni to mind, whereas the crowd scenes, the jump cuts, rapid-fire editing, and the movement of the masses are enough to make Eisenstein proud.

That’s why this rarely-screened film remains a worth to explore curio. The visual elements will not disappoint. At the time, it failed to make much splash. Piscator got busy with planning an anti-Nazi artistic center in the town of Engels.

Before it was set to open, he took a trip to Paris, from which he never came back-having ended up marrying a lovely (and rich) French dancer. When things began heating up in Western Europe, he moved to New York-and the rest is theatre history.

7. Carnival of Souls (1962). Dir. by Herk Harvey.

A David Lynch film made more than a decade before Lynch. Herk Harvey has made dozens of films, and won numerous awards for them. However, they were all industrial and educational films, made by the Centron Corporation in Lawrence, Kansas, for which Harvey worked most of his life.

Carnival of Souls, made for about $33,000, and utilizing actual locations and unknown and amateur actors, never really got a proper distribution at the time, as the distributing company went bankrupt. But over the years, it has developed a substantial cult following.

Very deservingly-Harvey concentrates on creating an eerie and unsettling atmosphere, with the help of smart location scouting (the abandoned Saltair Pavilion is a definition of eeriness) and experimental techniques.

He was able to keep the costs way down by his training and experience in making industrial thing-for instance, substituting the more expensive effects like rear projection with highly mobile Arriflex cameras and using natural lighting to great effect (the lightness and mobility of those cameras also made dollies and cranes unnecessary).

The eerie organ score also greatly contributes to the overall feeling of unease. The plot is nothing to shout home about-a car accident survivor relocates to a new town for a job, and weird things start happening.

Spoiler alert-if you have seen The Sixth Sense, you’ll guess where the plot is heading about 15 minutes into the film. But in this case, the journey is more important than the destination. It’s unfortunate that Harvey did not get to make another feature, but he at least lived long enough to see his only feature effort receive the recognition it deserves.

6. Nil by Mouth (1997). Dir. by Gary Oldman.

An often-overlooked Oldman-Luc Besson collaboration from the 90’s. Everyone knows the intensity of Leon or the garish fun of The Fifth Element. This one is typically overlooked. Shame-it’s, perhaps, one of the best films on alcoholism and its effects ever made.

Setting it in the impoverished area of London, Oldman refreshingly avoids moralization, focusing on the telling of the story instead. The typically stellar Ray Winstone again gives a fantastic turn as a brute of a man, matched by Kathy Burke as abused wife. The scene when he calls all their friends and family, drunkenly looking for her (soon after he gave her a savage walloping) is one of most concise and effective depictions of the nature of alcoholism.

Obviously, the film is a very personal project for Oldman, considering that he himself hails from New Cross, a London area much like the one shown in the film, and has endured a similar childhood. That may explain his reluctance to direct again, even though the film was received very favorably.

Perhaps when he feels again that he has a story that simply must be told, we’ll see him in the director’s chair. What remains is a quality film, with excellent turns, a fascinating story, and assuredly controlled elements, particularly the haunting and appropriate soundtrack by Frances Ashman, serving to combine the visual and the aural to give a strong one-two punch.

Not easy viewing, but definitely deserves to be seen. Some deal with traumatic childhoods with therapy, others-with drinking. Oldman took the best possible creative route.

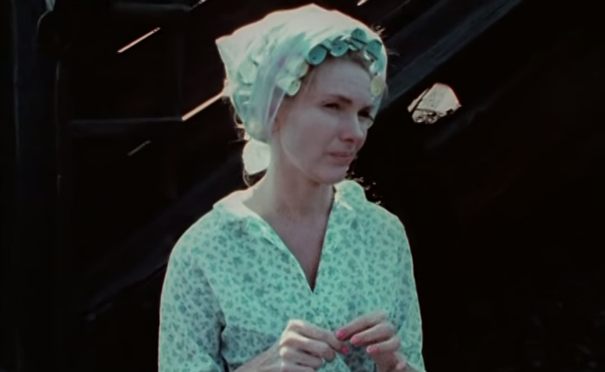

5. Wanda (1970). Dir. by Barbara Loden.

A former model, pin-up girl, and stage star, Barbara Loden made a film that is decisively glamour-free. Channeling her own inner demons and her own perceived place in the world, she starred in and directed a hyper-realistic masterpiece about a marginalized outsider. Her Wanda has all the emotional spectrum of not even a reptile, but a plant.

From the very opening, where she shows up in the courtroom with curls in her hair, and watches nonchalantly as her parental rights are being terminated, Loden establishes a uniquely apathetic character. She gazes emotionlessly at the world, even as it crumbles around her.

Hooking up with a hotheaded and abusive small-time crook, she goes on the meaningless ride across the backroads with him, eventually ending up pretty much where she started. Structurally, it’s similar to Fellini’s great Nights of Cabiria-but Wanda has none of Cabiria’s charm and personality (in fact, she has none).

Barbara Loden, at the time married to the great Elia Kazan, was able to make this minor masterpiece for about a $100,000, with herself and Michael Higgins being the only professional actors. Her years of being on the stage and learning from Kazan and others really show, as she completely inhibits the character, while allowing lots of space for herself, Higgins, and the non-professionals to improvise.

Along with the grainy 16mm. stock, this gives the film a verite feel achieved by few others at the time (or since). But it may have come a few years ahead of its time. Despite high accolades earned at the Venice Film Festival, the film received virtually no attention in USA at the time.

Loden would die of breast cancer in 1980. Her only feature film is, perhaps, her greatest legacy, surpassing her stage and screen roles, or even her Tony award, and influencing generations of future independent filmmakers.

4. One-Eyed Jacks (1961). Dir. by Marlon Brando.

Brando was never one to play by the rules, and it’s no surprise that in his hands a time-honored genre like Western would undergo a transformation. And Brando doesn’t disappoint-introducing deeper character development and human element to the horse opera, he comes up with a fascinating character study.

Notice the pattern of the films on this list directed by actors-they are very likely to impress with performances and character, rather than storytelling or technical elements. Marlon himself does a great job as the smoldering, revenge-driven Rio, as does Karl Malden as Dad, his former partner who betrays him.

Brando also gets quality supporting turns from such diverse cast as the iconic Mexican actress Katy Jurado, rodeo cowboy turned stuntman turned Oscar-winning actor Ben Johnson, and the inimitable Slim Pickens (Major Kong in “Dr. Strangelove).

But the production history was long and arduous. The script was initially written by Rod Serling, and then another draft by Sam Peckinpah. Stanley Kubrick was set to direct it, but Brando succeeded in ousting him, and completely took over as star, director, and producer.

While a great actor, and good at working with actors, he proved a complete greenhorn as a director, shooting six times the amount of film normally used, and extending the schedule by months and cost-by millions. The director’s cut that he turned in ran for about 5 hours.

The nervous studio has decided that enough was enough, and took over, whittling it to a more reasonable two and a half hours, prompting much anger from Brando. But even in a cut form, the film retains power and intensity, well on par with the best works of Anthony Mann, Sam Peckinpah, and Sergio Leone.

It could be argued that the film is a bridge of sorts, connecting the Westerns of John Ford and Mann to those of Leone and Peckinpah. The elements are there too-it was the last film shot on VistaVision. But the experience and his own nature made Brando loath to direct ever again.

3. Commissar (1967, rel. 1987). Dir. by Aleksandr Askoldov.

A masterpiece shelved, a promising talent suppressed. Soviet Union was never an easy place to make honest and creative cinema. But Askoldov’s fate stands out, probably no other Soviet director was treated like this.

The story is simple, at first glance. Askoldov adapted a very short (4 pages) story by Vassily Grossman, set in the town of Berdichev during the Russian Civil War.

In it, a Red Army commissar (a woman of rigorous political stance and steely resolve) finds herself unexpectedly pregnant, and is billeted upon a poor Jewish family. They provide her with comfort and aid in childbirth, while she is exposed to the world where not everything is black and white (or red and white, in her case). But in the end, she is forced to make a harrowing decision, as war wait for nobody.

It’s impressive that Askoldov managed to make a feature-length film out of such a short story. Doubly impressive is his assured control of the elements. His principle actors were all well-known and experienced, and yet the novice director, with only a year of directing workshop behind him being his only cinematic training, managed to get out of them some of the best performances of their long careers.

Nonna Mordyukova is superb as a large and monumental warrior of a woman who is forced by nature to be a woman for a time being, a mother. She is easily matched and often out-played by the great Rolan Bykov as a very Sholom Aleichem character, a sort of fiddler who came down from the roof and works as a blacksmith.

Despite being poor and having a large family to support (and now a new guest), he is organically incapable of being sad for too long. The technical elements are on the high professional level too, from crisp and mobile black-and-white photography to haunting music, written by a very young Alfred Schnittke.

So, why is it Askoldov’s only film? Several reasons contributed to its and his banning. First, prior to enrolling in the director workshop, Askoldov worked as a Deputy Minister of Culture, in charge of checking works of literature and theatre for ideological purity. Doubtless, his former colleagues came down extra hard on the renegade.

Secondly, 1967 was a bad year for Soviet-Israeli relations. The large amounts of economic and military aid that USSR provided to the Arab countries went up in smoke as Israel routed those Soviet allies during the Six Day War. So, a film where Jews were so favorably portrayed was probably doomed from the start.

Particularly, it was rumored, were the Communist anti-semiticists enraged by a harrowing short scene of the Holocaust flash-forward. Finally, even though Askoldov adapted a story that was first published in 1934 and since then reprinted numerously, the recently deceased author was in the Politburo’s doghouse.

Prior to his death, several of his manuscripts were confiscated, including his legendary anti-totalitarian novel “Life and Fate” (Suslov, the chief Soviet ideologist, assured the author that this novel will not be published in USSR for 200-300 years). And so, Askoldov’s film was banned and confiscated (miraculously avoiding complete destruction), and he was fired from the studio, labeled “professionally incompetent”, expelled from the Communist party, and driven to a near-death from heart attack. His only other (at the time, unofficial) directing credit is a 1972 documentary about trucks.

Fortunately, during Perestroika and glasnost, Askoldov was able to break the wall of lies and silence about his film. A copy was found, and it began its triumphant march through the film festivals of the world.

Now it’s considered a genuine classic, and Askoldov is a respected author and film teacher. But, being 83 already, it’s unlikely that he’ll ever make another film. Sad, and another strike for the Communist regime.

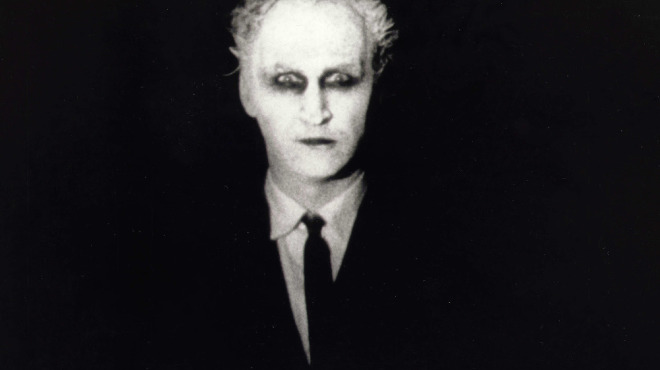

2. The Night of the Hunter (1955). Dir. by Charles Laughton.

A magical and stunning film. Even though it’s sadly the veteran actor Charles Laughton’s only one, it alone establishes him as a great director.

Having achieved fame as a stage actor in England, and translating it into film stardom on both sides of the Atlantic, Laughton assuredly tackles Davis Grubb’s eponymous novel. The expressionistic, Southern Goth prose is notoriously hard to film-and yet Laughton achieves near-perfect results.

Aided by his co-writer, the famous critic James Agee, the talented composer Walter Schumann, and the legendary cinematographer Stanley Cortez, Laughton paints an allegorical masterwork on the subject of good versus evil. A diabolic conman ingratiates himself into the family of his executed former cellmate to find out where the money is hidden.

After offing the widow, he pursues the escaped children across the backwaters. Laughton’s casting choices are nothing short of amazing. Aged Lilian Gish is great, and so is Shelley Winters as naïve wife. The most magnificent of all is Robert Mitchum as a serpentine preacher with LOVE and HATE tattooed on his knuckles, quick with a sermon and even quicker with a switchblade.

He easily belongs in the top-10 of all-time villains. The whole film has a feel of a nightmarish fairy tale, done by a master of German Expressionism. The sequence of children travelling by boat through a starry Southern night is nothing short of fantastic.

But, the film came out to a cool reception. Neither critics nor audiences were too excited about it at the time. As a result, Laughton’s subsequent directorial projects stalled, and he died in 1962 without realizing them. Over time, though, The Night of the Hunter slowly won the audiences over, and is now generally a recognized masterpiece. Not to be missed.

1. L’Atalante (1934). Dir. by Jean Vigo.

Film directors generally don’t die at 29. In fact, most don’t even debut at that age. Jean Vigo lived a short and difficult life, and this masterpiece is his sole feature. His entire filmography clocks in at just over two and a half hours. But we should be thankful that we got even that.

For “L’Atalante” is a genuine masterpiece and a work of pure art. If you ever start losing your love for arts or cinema, watch it-and the good feeling will return. Taking a deceptively simple story, Vigo makes a visual and emotional feast out of it.

Many sequences are simply unforgettable-the barge floating in the morning mist, the desperation of a groom who thinks he lost his bride forever, the frenzy of the Parisian life and lights that surrounds the prodigal heroine, the wedding march in the twilight-the list can go on forever.

Vigo showed that to be great, a film does not need a budget that is well over a GDP of most countries in the world, a cast of thousands, or a complex infrastructure. Just a few well-placed artistic elements, some competent and talented collaborators, and a vision.

Vigo was greatly aided by the talented cinematographer Boris Kaufman (Dziga Vertov’s brother, later famous for “On the Waterfront”, “12 Angry Men” and other masterfully shot films) and his three professional, engaging, and experienced leads, the best of whom was the inimitable Michel Simon as a gruff captain’s uncle.

The music by Maurice Jaubert, who epitomized the French music of poetic realism, is also unforgettable. All the more laurels for Vigo-these talented people did some of their best work for his film.

Sadly, it was his last. Plagued by poverty and TB, Vigo didn’t spare himself during the production, and was on his deathbed soon after turning in his cut of the film. While he lay dying, the producers effectively mutilated it and inserted a popular chanson to increase the profitability.

Legend has it that the very same song “Le chaland qui passe”, was sung by the street singer as Jean Vigo was passing into the next world. His artistic legacy is “L’Atalante” and three shorts. But it’s a classic example of quality trumping quantity, as Vigo managed to create enduring masterpieces and influence the course of French and world cinema. Merci, Jean.

Honorary mention: “Quick Change”-Bill Murray (he may have another coming out soon)

Really wanted to write about this quirky clowns-as-robbers number by Bill-freakin’-Murray, but he is rumored to have another one in the works and coming out soon. Still, don’t miss it-that good.

A very dishonorable mention: “Manos: The Hands of Fate”-Harold P. Warren

A cheap quickie made on a bet by a fertilize salesman, and it’s exactly as bad as it sounds. No review can do it justice-just watch the “Mystery Science Theater 3000” episode, Joel and the robots will tell you everything you need to know about it. Large quantities of alcohol are a must.

Bizarre mention: “Equinox”-Jack Woods and Dennis Murren.

A weird monster B-movie, and probably a direct inspiration for Evil Dead, it is a sole feature on the filmographies of both directors, one of whom (Murren) would go on to win 9 Oscars for special effects. This connection helped the film achieve cult status and a handsome Criterion treatment.

Others, left out for one reason or other:

“One Chance Out of Thousand”-Levon Kotcharyan: more fascinating for the Tarkovsky connection.

“Renaldo and Clara”-Bob Dylan: just really weird and out there.

“Johnny Got His Gun”-Dalton Trumbo

“Electra Glide in Blue”-James William Guercio: a very strange police procedural

“The Telephone Book”-Nelson Lyon

“Return to Oz”-Walter Murch

“Time Limit”-Karl Malden

“500,000”-Toshiro Mifune

“Strays”-Vin Diesel

“Short Cut to Hell”-James Cagney

“The Brave”-Johnny Depp: a case for why actors shouldn’t direct.

“Canadian Bacon”-Michael Moore: Moore should have stuck to “documentaries”.

“Bold Adventure”-Joris Ivens

“Gangster Story”-Walter Matthau

“Harlem Nights”-Eddie Murphy: see The Brave, a few spots above.

“The Buccaneer”-Anthony Quinn: not bad, but way too conventional.

“Windows”-Gordon Willis: proof that an ingenious DP does not always makes for the best director/

“Paganini”-Klaus Kinski

“Maximum Overdrive”-Stephen King

“Katinka”-Max von Sydow

“Tiny Furniture”-Lena Dunham: not bad, but too mumble-core for its own good. Stick with TV, Lena.

“A Nightmare on Elm Street”-Samuel Bayer: Bayer was great at music videos, not so at features

Author Bio: Leo Poroshin is a Russian-born aspiring writer/director (film and theatre), residing in Michigan. He enjoys life, and, naturally, the arts, as they are one of life’s best manifestations.