17. Outrage (2010)

This offering from Kitano’s later career is also one of his most gruesome (which is a tall order). Rampant with double-crosses and a marathon of a body count, none of the characters emerge entirely unscathed.

Between all of this is digressions into yakuza politics depicted in procedural fashion: ties are formed and broken, retaliation, revenge, and reciprocation, repeat. Reportedly, Kitano began writing the screenplay by detailing the deaths of various characters and filling in a plot around it. Said plot is, suffice it to say, a chaotic spiral of betrayal through the food chain of the syndicate.

Kitano is certainly cynical of the yakuza idea of honour and, in this film, practically to the point of parody. His technical approach is cold and restrained and character development is irrelevant for the violence is not cathartic but simply obligatory (though the vehemence of the various methods employed to accomplish this end is often startling).

In many ways, Outrage is the brash cousin to Sonatine where death is not to be feared or bartered with but distributed merely to make a statement.

16. Youth of the Beast (1963)

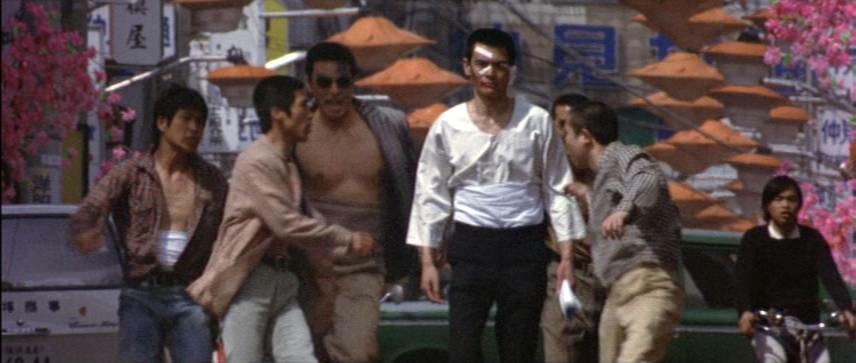

Seijun Suzuki continues his gaudy cinematic spree with Yaju no seishun, a film which would burgeon his stature as an uncompromising artisan as equally skilled technically as he was imaginative. With elaborately designed set pieces, sociopathic characters, and ferocious misogyny, the sheer torrent of bombastic ideas is somehow never overwhelming and always refreshing.

Here, Shishido plays ex-cop (and ex-con), Jo Mizuno, who becomes employed by a yakuza gang by beating up their lackeys and refusing to pay his bar tab. How else? Of course this is all a plot to revenge the murder of his former partner. Pink siroccos, pop art deco, and various other trancelike imagery lay the foundation for what was to become Suzuki’s most defiant period.

Shishido deftly plays two rival gangs against each other in pure Yojimbo fashion with morbid wit and indifference. Stringing together a plot involving something about a knitting school and a gay yakuza who uncontrollably slashes anyone who insults his mother, one can not only count on Suzuki to somehow combine all of these oddities into a single film but also revel in the absurdity of it all with eruptions of colour and blasts of jazz music.

15. Stray Dog (1949)

Akira Kurosawa (Rashomon, Seven Samurai, The Hidden Fortress, Ran, Kagemusha, Throne of Blood) is not readily known for his yakuza films, but it is testament of his versatility that two of those films manage to make an appearance on this list.

Part documentary, part police procedural, part neo-realism, part noir, Kurosawa blended traditional Western influences for a wholly unique brew which would, in time, come full circle and influence the rest of the cinematic world.

Toshiro Mifune plays Murakami, a rookie cop who, at the start of the film, has lost his gun. The plot follows his obsessive hunt through the black markets, brothels, bars, and dancehalls of postwar Tokyo in a desperate attempt to save face.

It isn’t long before Murakami’s gun is used as a murder weapon and the search intensifies further. Veteran actor Takashi Shimura stars as Detective Sato, a senior officer who brings some much needed advice and experience to Murakami’s often hard-edged approach.

Kurosawa reportedly wrote the story as a novel before adapting it into a screenplay heavily influenced by the meta-mystery novels of Georges Simenon.

As an additional note, most of the scenes involving footage of the black markets was shot guerilla-style by Ishiro Honda (director of the original Godzilla as well as many its sequels and other signature tokusatsu films such as Mothra and Rodan) in actual black market areas at the time.

14. Battles Without Honor and Humanity: Deadly Fight in Hiroshima (1973)

Fukasaku’s grand series follows the exploits of Shozo Hirono and a myriad of other yakuza members in a sprawling document of family grudges and dealings within the syndicate. This second film in the series, Deadly Fight in Hiroshima, is the only one to shift focus from Hirono to a loner named Shoji Yamanaka (Kinya Kitaoji).

Once having aspired to become a Kamikaze pilot (because, of course, he has a perpetual death wish), Yamanaka instead joins the Muraoka family partially out of his attraction for Muraoka’s daughter, Yasuko (Meiko Kaji). As is a common theme in the series, rival yakuza families are headed by manipulative bosses who exploit their subordinates as often as possible.

In contrast with Hirono’s firm and collected character, Yamanaka is moody and often loses motivation in completing his duties (despite being quite adept at killing gangsters), embodying wholeheartedly the fatalistic archetype. Also of note, Sonny Chiba makes an appearance as Katsutoshi, a gleefully antagonistic gangster who just doesn’t like Yamanaka for no good reason.

13. Street Mobster (1972)

An almost constant whirlwind of frantic energy, Street Mobster tells the tale of a group of misfits who are desperate to make a name for themselves in Kawasaki. They are led by Isamu Okita (Bunta Sugawara), the most rambunctious of the lot. He is an orphan whose birthday falls on the day Japan lost the war and makes a living through pimping and extortion.

His refusal to compromise with the local Takigawa yakuza family however earns him jail time and his gang is subsequently abandoned. Upon his release he forms a new gang and hatches a plot to provoke contention between the Takigawa family and their rivals, the Yato family.

Boss Yato (Noboru Ando) sees something of himself in Okita and takes him under his wing despite Okita’s arrogant reluctance to accept help. Yato repeatedly covers for Okita’s recklessness in order to avoid a gang war but when Okita is ungrateful for Yato’s sacrifice of yubitsume he is banished from the family to fend for himself.

Frequently, Okita becomes victim to his own stubbornness as if he intentionally sets out to make things more difficult for himself and his fellow delinquents. Fukasaku’s longstanding criticism against the pretense of honour concludes once again with violence and mayhem.

12. Tattooed Life (1965)

Seijun Suzuki took a break from trippy oddball films to make a ninkyo eiga (chivalry film) set in prewar Japan. Gone is the ludicrous plotting and over-the-top violence but the elaborate set design and technical virtuosity is thoroughly retained, the film could even be, daresay, elegant! Tattooed Life takes its time to develop its characters and define their motivations before the final trial of resolve.

“Silver Fox” Tetsu is a hitman who, along with his delicate younger brother Kenji, is on the run after killing a yakuza boss in a vicious betrayal. They plan to flee to Manchuria but are swindled out of their boat fare and must work for a construction company. Kenji falls for (of all women) the foreman’s wife which lands the pair in hot water.

In fact, Kenji is the catalyst for practically every conflict in the film all the while bemoaning in a relentlessly pitiable state. It isn’t long before Tetsu’s rival gang tracks him down and chaos ensues.

The film’s slow burn finally culminates with an impressively choreographed action sequence where Tetsu battles a large wave of yakuza. The sequence lasts nearly ten minutes and is easily one of the most epic finales in the genre.

Suzuki discards the previous hour of restrained drama for his signature expressionism with floors that disappear and gunshots flashing in utter darkness, bouquets of colour and spectacular swordplay. The drastic tone change is yet another cheeky proclamation by the veteran filmmaker.

11. Sonatine (1993)

Oft-regarded as Kitano’s most accomplished yakuza film, it was a commercial bomb in Japan upon release. Not entirely surprisingly given the quirky, pensive tone punctuated by bouts of concentrated disquiet.

Murakawa (Kitano) is sent to Okinawa to settle a dispute between two yakuza clans. Not soon after his clan’s headquarters is bombed, he and the remainder of his men escape to a beach house and wile away their days playing games which often end up being extremely dangerous (such as rock, paper, scissors with a Russian roulette twist).

Foreshadowing the fatalism of the yakuza, in one sequence the disenfranchised gangsters shoot fireworks at each other until Murakawa starts firing a gun. No one seems to mind and the game continues.

Sonatine is a bizarre montage of surrealist touches such as an assassin disguised as a fisherman who appears during a Frisbee match or a scene where Murakawa calmly watches a man attempt to rape a woman until the man confronts him to which Murakawa calmly responds by shooting him.

The Murakawa character admits that he is tired of living and does indeed seem to be caught in a perpetual state of indifference where life is irrelevant and death is only an end to meaningless violence.

In one final stroke of mayhem, two clans meet at a hotel only to be upstaged by a power outage caused by Murakawa. The resulting massacre is entirely off-screen but even this triumph Murakawa regards as mere duty. There is no victory, there is no loss; there is only the flashes of light in between.

10. Ichi the Killer (2001)

Ichi the Killer is Takashi Miike’s most violent and controversial cinematic offering (and that’s an imposing statement) which opens with a title sequence literally emerging from a pool of semen. The film is a masochistic, byzantine romp littered with inhuman (or all too human) cruelty and gallows humour unsettling not only in its disturbing imagery but by eliciting uncomfortable comedy.

The plot is a quagmire of psychological manipulation, surrealism, and graphic excess. Underboss Anjo is murdered in his apartment by repressed psychopath, Ichi (Nao Omori).

The crime is then meticulously covered up by a man named Jijii (Shinya Tsukamoto) and his competent cleaning crew. Kakihara (Tadanobu Asano), Anjo’s ruthless enforcer, along with his fellow yakuza, can only surmise that Anjo skipped town with the ¥3 million missing from the gang’s funds.

Kakihara entertains suspicions that Anjo was possibly kidnapped by a rival gang and his fateful meeting with Jijii leads him to torture and murder an increasing number of yakuza. That Kakihara’s methods cause even seasoned yakuza to avert their eyes is testament to his effectiveness and yet, Ichi, who remains an enigma for much of the story, is substantially more sadistic.

Based on the manga series by Hideo Yamamoto (Homunculus, Yume Onna), the film is rife with unapologetic violence probing the extremes of nurtured killer and natural born killer.

9. Violent Streets (1974)

Real-life yakuza, Noboru Ando, stars as Egawa, a former boss of his own family who was forced to retire by his superiors. As compensation he was given a flamenco nightclub called The Madrid, a moderately successful business he maintains chiefly as a hangout for his former gang.

When his former gang secretly kidnap a pop singer for an exorbitant ransom, it doesn’t take long for the syndicate to ascertain their identities. When the singer is accidentally killed, the kidnappers begin turning up dead as well.

To make matters worse, the syndicate is rescinding its gift to Egawa and demand he return The Madrid to them (for a generous payoff of course) so that they can solidify their control of the district.

He balks as it was always intended as his gift to the loyal men who have stood by him. He is peaceful in these protests until his friends begin dying and he is implicated in the kidnapping scheme he knew nothing about.

Ando is in excellent form here as a tired ex-enforcer whose retirement from violence is thoroughly doomed. Parting with an image of caged chickens (several of which are shot to pieces), Gosha alludes to the yakuza life as a trap partly self-induced but ultimately irremovable from fate.