8. A Colt is My Passport (1967)

Joe Shishido, who was to star in Seijun Suzuki’s Branded to Kill later the same year, plays hitman, Shuji Kamimura. Left out to dry by his greedy, duplicitous boss, Kamimura and his sidekick Shiozaki are hunted by two rival gangs intent on blood. The two men hideout at a tavern in a seaside town where they meet a woman named Mina who may be able to offer them means to escape.

Fantastic gundowns and memorable hard-boiled characters populate throughout with Shishido portraying his signature legendary archetype. The final faceoff takes place at a landfill curiously reminiscent of a Western film and choreographed with expert precision.

Complete with a Morricone-esque score by Harumi Ibe, the film bleeds noir, bows to French New Wave, and echoes Suzuki’s stylish action romps buoyant with energy and rife with experimental aplomb.

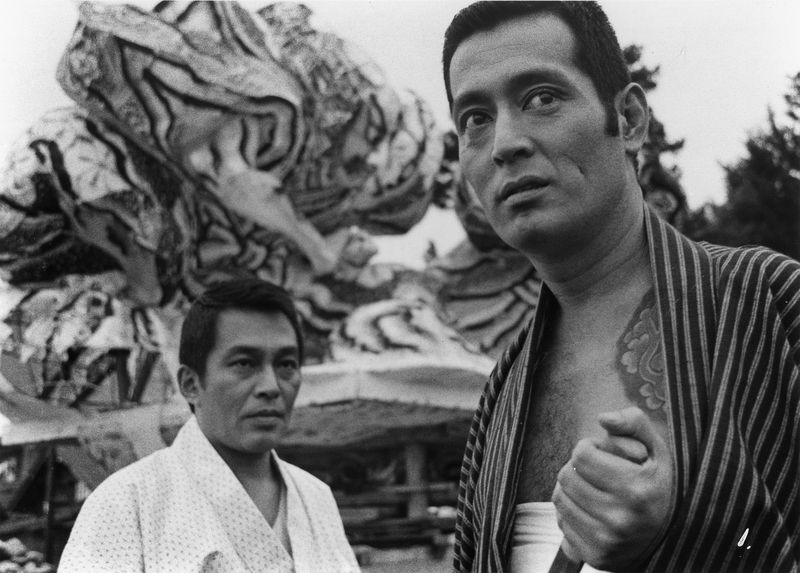

7. Graveyard of Honor (1975)

Based on the life of Rikio Ishikawa, Fukasaku once again provides a masterful epic of bloodlust and general madness with Tetsuya Watari in the lead role. Ishikawa is a looming figure who is reckless as hell while seeming immortal as he carelessly thrusts himself into dire situations but emerges, more or less, unscathed.

It is this rise and fall (but mostly fall) of one of the most infamous self-destructive characters in the genre which ranks Graveyard of Honor (an aptly titled film if ever there was one) so high on this list.

Throughout the film Ishikawa insists on controlling his own destiny even while tempting fate. From ceaselessly shooting heroin to overcoming impossible fights by sheer audacity he defies death without a sense of victory. His fate is always held firmly in his own hands until one final act of rebellion against humanity. If ever there was a character to herald sociopathic nihilism as an art form it is undeniably Rikio Ishikawa.

6. Battles Without Honor and Humanity (1973)

Fukasaku’s baroque five-part Battles Without Honor and Humanity series was filmed in only two years and marked a departure from the ninkyo eiga films depicting honourable yakuza. Fukasaku’s work in the genre is grim and frenzied where characters act more on passion than strategy. Adapted from a series of newspaper articles based on the career of real-life yakuza Kozo Mino, it is a sprawling meta-history of family treachery within the syndicate.

While the series features dozens of characters whose fates all play a part in an uncompromising immensity of interconnected feuds, pacts, and duplicities, the series tends to focus primarily on Shozo Hirono (Bunta Sugawara), an ex-soldier who, at the beginning of this film ends up killing a yakuza to protect a friend and is subsequently imprisoned.

While inside however he befriends a gangster named Hiroshi (who, in an outrageous sequence, manages to skip his prison sentence by intentionally botching an attempt at hara-kiri) who eventually bails him out and gets him into a syndicate family. What follows is one misdeed after another as Hirono’s resilience is tested and brother betrays brother under the pompous eye of opportunistic bosses.

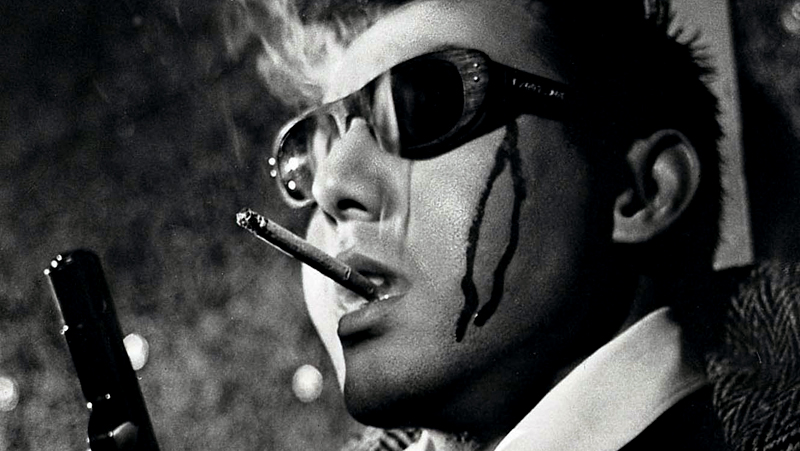

5. Branded to Kill (1967)

Koroshi no rakuin follows the exploits of Goro Hanada (Joe Shishido), hitman and general tough guy. Complete with Suzuki’s incredible set design (there is a sequence featuring an apartment ornamented with dead butterflies that is quite disorienting) and peculiarities (at one point a butterfly lands on Hanada’s sniper rifle causing him to miss a target), the film is an audacious feast for the senses.

Through various circumstances, Hanada and his fellow assassins develop a comical mania of keeping track of “killer rank” until all that remains is Hanada and the phantom Number One Killer.

The film’s entire third act is comprised of their game of cat and mouse with Number One repeatedly intoning, “This is the way Number One works.” Their final faceoff is a masterfully satirical sequence that is tragic, victorious, and absurd all at the same time.

Seijun Suzuki has appeared several times on this list but all of the previous entries seemed to inevitably lead to this one. It was the last film he directed for Nikkatsu Studio who, at the time, found his output increasingly tiresome.

With each successive film they reduced his budget until, in 1967, he was relegated to only shooting in black and white and with the thinnest shoestring budget. Instead of constricting Suzuki to conventionality this caused him to experiment even further and develop outrageous sequences out of a fairly basic screenplay, and the quickness of the shooting schedule afforded him greater freedom to do this.

Unsurprisingly, upon release, it was a critical and commercial failure resulting in a ten-year blacklisting. It also made him a counterculture icon, uncompromising to the last.

The film is characteristic of the filmmaker consisting of the finest facets of his style: the eccentric antihero (here, Hanada, has a fetish for boiled rice), experimental editing, mythical gunfights, and preposterous plotting.

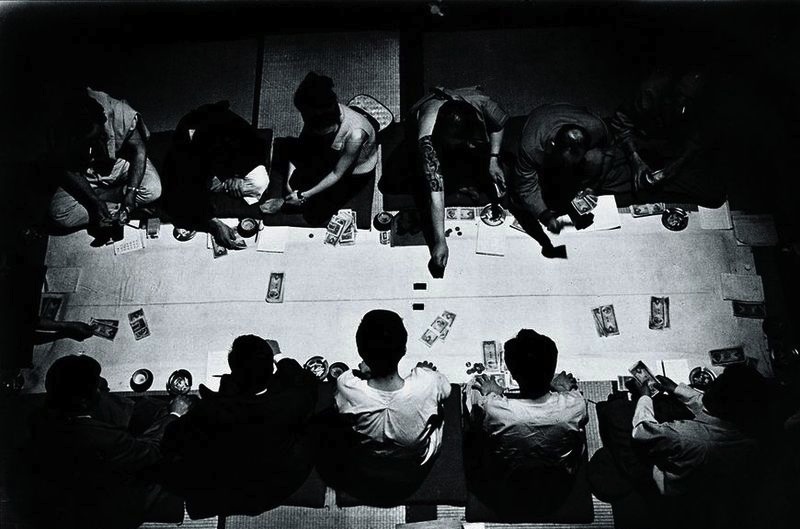

4. Pale Flower (1964)

Masahiro Shinoda is a master craftsman at framing and composition (just soak in the simplistic majesty of such films as Himiko, Gonza the Spearman, Double Suicide, Chinmoku, and With Beauty and Sorrow to name but a few) but he’s also a fine storyteller whose plots have ranged from chambara to fantasy to mystery to espionage.

Kawaita hana tells the tale of Muraki (Ryo Ikebe), a senior hitman recently released from prison. He is detached, honorable, and quietly idealistic, never questioning his boss and never grumbling when confronted with misfortune. He spends much of his time playing oicho-kabu floating from one gambling parlor to another until he meets a woman named Saeko (Mariko Kaga) who allures him with her clandestine beauty. She is to become his undoing as much as he is to become hers.

Pale Flower was an early entry in the Japanese New Wave but it was also directed inimitably by Shinoda where style and substance are inseparable. It is one of the more unique entries in this list as well as being Shinoda’s only yakuza film. In addition, the always brilliant Toru Takemitsu provides the score with chameleon mystery.

3. The Wolves (1971)

Filmmaker Hideo Gosha is perhaps best known for his chambara films (Hitokiri, Three Outlaw Samurai, Sword of the Beast, Samurai Wolf), however, his versatile vision extended to the ninkyo eiga (chivalry film) as well.

While most of the films presented on this list take place in postwar Japan, Shussho Iwai focuses on the late 1920s when, to celebrate Emperor Hirohito’s rise to power, countless yakuza were pardoned and freed to roam the streets.

Tatsuya Nakadai plays Seiji Iwahashi, a yakuza underboss formerly imprisoned for killing a rival boss. Upon his release, he pines for the loss of honour in the underworld and struggles to combat the increasing moral decay of civilisation. He comes to find that the boss of his gang has died and his sworn brother has taken over with greed controlling all.

Gosha goes to great lengths in favouring character development over mêlée but violence, when it erupts, is grueling and messy. Interspersed with Iwahashi’s bitterness and Nakadai’s vacant stare, The Wolves is one of the most socially subversive films on this list. A labyrinthine plot which takes its time revolving in a place devoid of honour inhabited by wolves without integrity.

2. Sympathy for the Underdog (1971)

It is perhaps regarded as a crime to undermine Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honor and Humanity series, but this gem heightens the yakuza struggle by displacing it. Though originally intended to be set in Vietnam, Fukasaku retained focus on making a film about outsiders and Sympathy for the Underdog was born.

A yakuza boss named Gunji is cast off his turf in Yokohama by a rival Tokyo gang. Gunji organizes his most loyal mobsters and relocates to Okinawa where they celebrate a bloody, short-lived presence. A final confrontation ensues when the same Tokyo gang descends to overtake their newly acquired turf in a poetic bloodbath that would make Sam Peckinpah proud.

Fukasaku has been mentioned many times over in this list and quite deservedly so. He is arguably the penultimate filmmaker on the subject having pioneered and established much of the genre’s characteristics (granted with a more cynical slant) along with his predecessor, Seijun Suzuki.

1. Drunken Angel (1948)

The first collaboration between pioneering filmmaker, Akira Kurosawa, and famous actor, Toshiro Mifune tops the list as the greatest yakuza film in cinematic history. For one, it is quite possibly the first cinematic depiction of post-war yakuza and began several reoccurring tropes in the genre.

Matsunaga (Mifune), a young mobster, is diagnosed with tuberculosis by the local doctor, Sanada (Takashi Shimura), who is himself an alcoholic. The two form a volatile relationship with Matsunaga continuing to live a consumptive lifestyle despite Sanada’s advice to slow down.

As Matsunaga becomes progressively ill, the realization that his boss is preparing to sacrifice him to a rival gang looms ever closer. What results is a climactic knife fight that is pleasure to behold in its technical mastery and frantic acting.

Drunken Angel embodies the yakuza film simply and comprehensively: the self-destructive mobster divided by loyalty and integrity, conflicted by morality and duty.

It is also a deeply satirical film wherein Kurosawa criticizes the U.S. occupation prevalent at the time (any direct criticism was censored by the U.S. government), broadening the allegory and, once again, blurring the line between justice and corruption.

One frequent motif is a toxic pond in the center of the town where children often play, where naivety meets reality. The honour of a yakuza is matched only by his fatalism – this is the only moral ground.

Author Bio: Deckard is a gypsy with a deep-rooted love for culture and the arts. Fully ensconced with the belief that the written word is magic and music is the breath of life, he is musician always and writer when blessed.