17. The Forbidden Room

An archipelago of film fragments as disparate as they are diverse from Canada’s resident weirdo, Guy Maddin, co-directing with young upstart Evan Johnson, The Forbidden Room is an oddity that certain viewers will applaud while others scratch their heads. Typical, really, for this sort of filmmaking without a safety net approach to instinctive and orphic myth-making.

A campy combination of crypto-confessional and classic Hollywood melodrama, The Forbidden Room is an audacious adventure, a fever dream, with episodic detours down, amongst other curious chronicles and cliffhangers, a flapjack-loving submarine crew, a sentient moustache, marauding bandits, kidnapped sweethearts, and more. It’s a compendium of absurd ideas, deep invention, and confounding comedy.

16. Beasts of No Nation

An unflinching eyewitness account of the horrors of war is what writer-director Cary Fukunaga offers audiences with his third feature film, Beasts of No Nation.

Child soldiers enacting sectarian violence doesn’t make for easy viewing but Fukunaga––no slouch here, he’s also the cinematographer–– lets loose with technical bravura with single take action sequences, slyly keeping his lens close to young Agu (Abraham Attah, brilliant) throughout.

When Agu, for instance, is numbed with narcotics, the urban wastes he inhabits become color scrubbed and filtered to reflect his roving mind. It may not be subtle but it’s highly effective. Relentless and raw, briefly tender, and all too traumatizing, Beasts of No Nation haunts the mind long after the final title scroll.

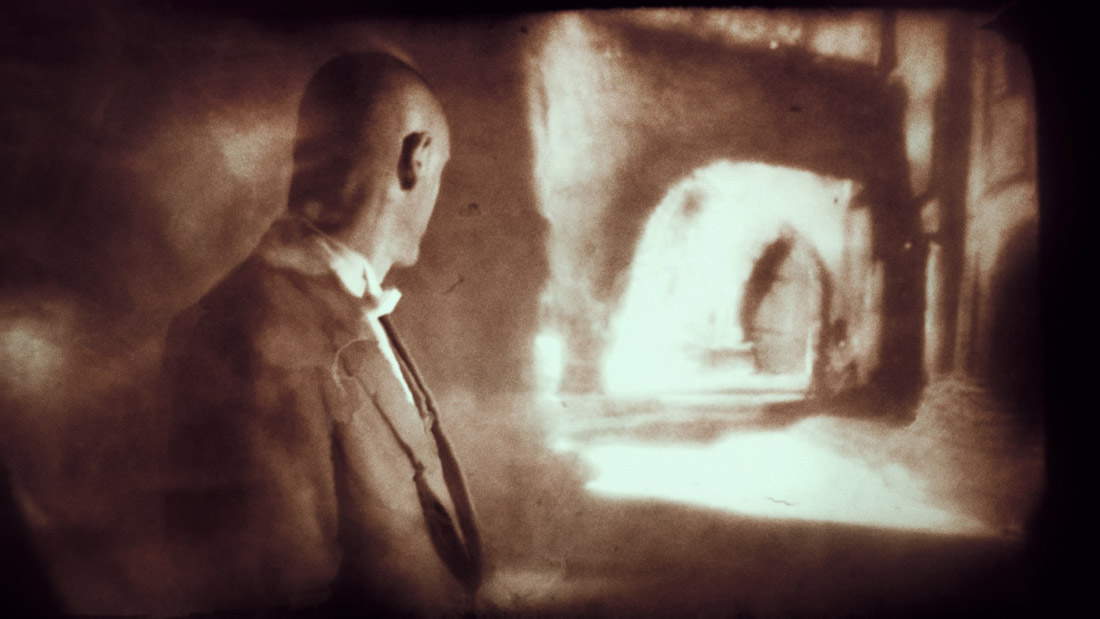

15. Crimson Peak

Guillermo del Toro’s blood-soaked love letter to Victorian-period ghost stories, Crimson Peak, kneels at the altar of Mario Bava, and the returns are rich and abundant.

The cobwebbed candelabras and blood-flecked vaults and terraces of Allerdale Hall, the derelict Gothic castle that upstages the A-list cast (which includes Tom Hiddleston, Mia Wasikowska, and Jessica Chastain), is the most intriguing aspect of the film, and the mineral rich clay deposits that stain the snow smeared grounds a blood red offer up the most memorable spectacle.

A visionary director with a cult following, del Toro’s Crimson Peak isn’t as all-out horror as his diehards demand, it’s more a Daphne du Maurier-style romance with outbursts of gore, but the stunning production design, elegant and elegiac set pieces, and the spooky mansion motifs all carry a velvet haul of visual flourish and abundance.

Cinematographer Dan Laustsen and production designer Thomas E. Sanders add to the dark beauty of del Toro’s snowy imagery and Machiavellian splash.

14. Creed

Ryan Coogler’s sports drama isn’t the predictable weak-kneed Rocky sequel everyone at first feared it would be. No, Coogler and trump card DP Maryse Alberti craft a kinetic and enthusiastic picture, one that, while not void of all the boxing movie clichés, is still a rousing thrill.

One visual pattern that Coogler makes much of is against the grain of this sort of picture where over cranked camerawork with high-speed jump cutting is the norm, here the viewer is treated to muscular long takes, and intense travelling shots containing tight choreography and intense technical braggadocio. The underdog tale Coogler depicts is reliant on is a crowd-pleaser with aplomb and considerable intelligence.

13. Brooklyn

An old-fashioned immigration tale of love in 1950’s Brooklyn gives Irish director John Crowley ample room to recreate a bygone era with an eye for detail and a generous knack for suspense-addled romance. Crowley and cinematographer Yves Bélanger take pains to mirror the mood and perspective of young lass Ellis Lacey (Saoirse Ronan, excellent), Irish expat ingenue, who moves from homesickness to first love and more (no spoilers here).

Brooklyn is an old school weepie with bittersweet predilection and no shortage of open vistas, textured lighting, lush, soft focus interiors and more. Sure, it’s a film that sidelines the harsher aspects of the immigrant experience in favor of orchestral swelling maudlin mooning, preferring to see the era of the film as an innocent age than with any rough edges.

But the wealth of likable characters, lavish locales and steep nostalgia will win over most viewers, particularly those who like their cinema safe, and delicate to decry.

12. White God

Kornél Mundruczó dives into magical realist territory in his high-reaching and fable-like tale of a 13-year-old girl and her dog, Hagen. And while the tone of White God wavers capriciously––one minute it’s a tender, coming-of-age tale, then an almost Disney-like Incredible Journey before morphing into a horror movie mandate––the streets of Budapest are lensed with love and brilliancy.

As the city becomes overrun with dogs, like a canine Armageddon of attrition, Mundruczó, cinematographer Marcell Rév, and animal wrangler Teresa Ann Miller create an adventurous, menacing, and redoubtable visage. Surely White God’s bold vision and incredible use of animals is what garnered it the Un Certain Regard prize at Cannes and must be seen to be believed.

11. High-Rise

British firebrand Ben Wheatley (Kill List, Sightseers) continues his run of rebellious and provocative cinema with the Grand Guignol satire of Thatcher’s England, adapted from the J.G. Ballard novel, with High-Rise.

Amidst the decadence and depravity on display, Wheatley and his regular cinematographer Laurie Rose get red in tooth and claw as they dissect the denizens of a 40-storey luxury building, over the course of three months, as they go native, reverting to ferocious barbarity, Freudian textbook extremes, and eye-popping excess.

Wheatley and Laurie dive into an immersive visual style that is as sensational––mirrored tableau in the elevators makes for one of many menacing motifs––as it is disturbing––a dazzling and deadly slow motion plunge into an automobile is impossible to turn away from.

High-Rise’s razor-sharp wit will get a rise from sensitive viewers, as will the serrated-edged comedy, envisaged with considerable shock and vibrant perception.

10. The Hateful Eight

Revisiting and reworking the Western genre once again, American auteur Quentin Tarantino and DP Robert Richardson chose to shoot The Hateful Eight in 70mm––an uncommon, high-res format––cheekily opening with a salvo of John Ford-like panoramas of snow-flecked landscapes before settling down into what’s essentially a one-room chamber film.

Despite the self-imposed limitations QT sets for his tale of betrayal and banter, visual flourish and frenzy is still present, just more subtle than we’ve come to expect from this maverick filmmaker.

Hemmed in, Tarantino and Richardson pack perceptible cues and visible information in an interior space that heightens the instilled panic of claustrophobia and cabin fever, like the desperate double-crossers that populate this Wild West passage. The Hateful Eight is as fetishized and profound as anything QT has done and ranks as one of his strongest and most ostentatious efforts.

9. It Follows

Director/writer David Robert Mitchell’s second film, It Follows, is a highly effective old school horror film, teeming with atmosphere and otherworldliness. Set in a decaying Detroit—the perfect illusory setting—Mitchell and his DP Mike Gioulakis go to town upping the creep factor, pulling focus on flashy frights, swaggering scenarios, and dauntless details, all of which belying the films low budget.

Their 360-degree pans invoke classic Brian De Palma, their tracking shots harken to Kubrick’s The Shining, the pulse-pounding score by Disasterpiece is an artful homage to Goblin and John Carpenter, the game cast, fully committed, land strongly on all the marks, and the end result announces the arrival of a new suspense master and his first small-scale but high-concept chef d’oeuvre.