7. The Last of Sheila (1973)

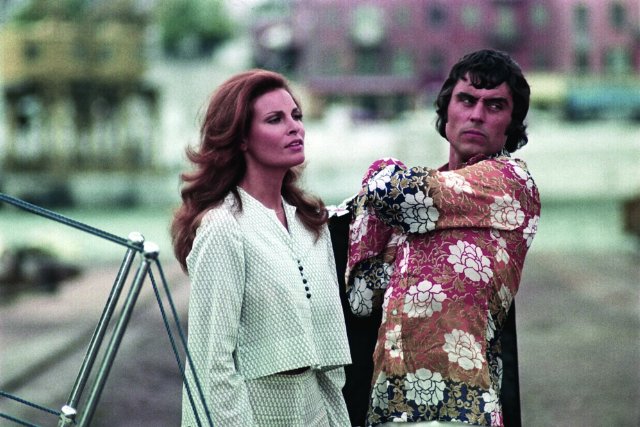

Director Herbert Ross’ horrifically forgotten murder mystery is one of the most twisted, entertaining, and wickedly funny entries on this list. Featuring a standout cast that includes (a hilariously nasty) James Coburn, James Mason, Raquel Welch, and Joan Hackett, The Last of Sheila is the kind of thriller (filled with outrageous twists and turns that daringly shift the film’s tone as much as the course of its plot) whose intelligence, wit, and (very dark) humor is something we don’t see enough of today.

Interestingly (and curiously) enough, the film’s screenplay was written by (then-future) Broadway musical giant Stephen Sondheim and Pyscho’s very own Norman Bates, Anthony Perkins.

Coburn plays a millionaire who hosts a weekend yacht party for his entertainment industry friends a year after his wife was killed by a hit-and-run driver outside of a Hollywood party. All six of Coburn’s guests take part in a very involved game he has set up: They are each given a card that has a crime written down on it.

As they soon realize, each of them has committed one of the crimes given out (but not to that specific individual) and things just get increasingly and joyously convoluted from there. By the time it’s over, The Last of Sheila succeeds on many levels. Like many films of the seventies, it’s not an easy film to categorize or put in a box, as it is (amongst other things) one of the most innovative murder mysteries ever put on film, and also one of the most biting and hilarious satires on Hollywood life of its time.

6. Over the Edge (1979)

This is the kind of movie that simply wouldn’t survive (or probably wouldn’t get made at all) in today’s market. Its tone is anarchic, its message is intelligently dangerous, and its outcome doesn’t really have a distinct or comforting moral message.

Over The Edge, as exemplified by a soundtrack that features The Ramones and Cheap Trick (amongst many others) is the then-burgeoning punk rock movement in cinema form: an explosion of emotion and anger that tears down the establishment without any thought (or pretensions to care) of what to replace it with.

Centering around a group of (primarily) ignored and severely bored teenagers who live in a closed-off experimental housing project, Over The Edge takes an almost surreal turn when it depicts these youths literally taking over their town and school. They barricade all authority figures in their school gymnasium during a town meeting, then have a great time breaking all hell lose as they vandalize and destroy everything around them.

Director Jonathon Kaplan (The Accused and Unlawful Entry) and screenwriters Tim Hunter (director of River’s Edge) and Charlie Haas created the classic anarchic film: fun, demented, angry, and undeniably passionate. It’s a great film for its times and for today, as its themes and events resonate even now… In spite of how wonderfully ambiguous and questionable the moral center of Over The Edge actually is.

5. Little Big Man (1970)

Once again, Dustin Hoffman shows us he is capable of anything in Bonnie and Clyde director Arthur Penn’s comically-toned historical fiction adventure. Hoffman plays Jack Crabb, a wily old man in the film’s beginning who recounts his days in the Old West being raised as a white man by Native Americans. What feels like a rambling (but highly entertaining) tall tale ensues, as Hoffman’s adventures ultimately lead him to playing a large part in General Custer’s last stand at the battle of Little Big Horn.

Hoffman’s comedic timing and sensibilities guide us through the sprawling epic. His ability to shift emotional gears on a dime, however, is what sells the movie when it dares to go its most dramatic (there is a harrowing sequence where Hoffman witnesses the slaughter of the Native American tribe who adopted him).

Hoffman, a movie star in the truest sense of the word, carries the film’s tonal shifts on his shoulders, and forces empathy from his audience every step of the way. It is a showcase of Hoffman’s talent to the fullest extent, which is what makes Little Big Man a must-see (though currently uncelebrated) classic of its time.

4. Blue Collar (1978)

Cowriter (with his brother Leonard) and director Paul Schrader’s film is a welcome entry to this list or just about any other list because it dares to go numerous places that many American films, from past or present, refuse to go.

It is an intelligent and dramatic representation of the working class system in America, the corrupt politics behind it, and the unfair (and possibly manipulated) racial relations that prohibit the possibility for any true progression. Blue collar workers are presented in the film as victims of modern-day slavery, a point of view that is as dead on and resonant today as it was in the seventies, but, unfortunately, also every bit as controversial and unpopular.

Starring Richard Pryor (whose comedic sensibilities are put to brilliant use in a dramatic role), Harvey Keitel, and the mostly unsung great Yaphet Kotto, Blue Collar is an unflinching, uncompromising, and quite discomforting exploration of the system that employs (and ultimately controls) the working class. Their place in today’s economy, and the rights that are withheld from them to keep them there, are what keeps the machine of the system alive… And in the hands of Paul Schrader, the lives presented in Blue Collar are powerlessly bleak traps that are virtually impossible to break free of.

3. Phantom of the Paradise (1974)

A disfigured composer whose music is stolen from him haunts the rock palace of The Paradise to punish those that did him wrong… Although it has a cult fan base and its influence on popular culture is perhaps more wide-ranging than any other film on this list, writer-director Brian De Palma’s camp masterpiece, The Phantom of the Paradise, is a film whose boldness, originality, and style has never gotten the due respect it’s deserved.

From Stephen Sondheim to The Cure to The Rocky Horror Picture Show to Repo! The Genetic Opera to Guilermo Del Toro (and everything else darkly fantastical, slightly androgynous, highly over-the-top, or kitsch-rich since), The Phantom of the Paradise is the ultimate cultural phenomenon that, quite curiously, never quite got the opportunity to be fully recognized as being so.

2. A Woman Under the Influence (1974)

John Cassavetes’ masterpiece may be the most celebrated film of his directorial career, but that doesn’t mean it’s anywhere close to getting the attention, discussion, or appreciation it deserves today. A Woman Under the Influence is Cassavetes (not to mention stars Gena Rowlands and Peter Falk) completely in his element and unquestionably at his best. The film is raw, emotionally exhausting, messy, and completely and utterly alive.

A Woman Under the Influence follows a married couple trying to coexist with the wife’s mental illness. Miraculously, as draining and unrelentingly powerful as the experience is, the film doesn’t wallow in negativity or sadness.

It honestly depicts the couple’s darkest trials and tribulations and, ultimately, becomes one of the most optimistic and romantic films about real-life love ever made. The experience is truly one-of–a-kind, and is every bit as groundbreaking when compared to films made today as it was when released over forty years ago.

1. Sorcerer (1977)

William Friedkin’s highly uncelebrated masterpiece is a true rarity: an art film in disguise as an escapist yarn. Deserving a place right next to his most respected works, Socerer had the misfortune of arriving a few years too late in a decade whose tail end primarily wanted pure escapism amongst its mass film-going audience. The film is as thrilling and exciting as they come, but also ends just as bleakly and uncompromisingly as any of the films Scorsese, Peckinpah, or DePalma were dividing audiences with at the time, as well.

Sorcerer stars Roy Scheider as the head of a group of men hired to transport highly sensitive dynamite across the South American jungle. The film’s set piece, featuring a large truck filled with the explosives (that could literally go off at any second) having to cross the rockiest and most unstable bridge ever put on film, should have been just as iconic of a cinematic Friedkin moment as his car chase in The French Connection or Linda Blair vomiting pea soup in The Exorcist.

The film’s somewhat depressing nature, along with its decision to conclude as a meditation on never-ending personal obsession, however, kept it from reaching the audience it deserved.

As is so often the case with many forgotten masterworks of any artistic medium, Sorcerer was a case of bad timing. The film may have contained some of the most thrilling and expert filmmaking of the decade, but it also offered a harsh reality that wasn’t neatly wrapped up or contrived to provide its audience with any form of relief.

Sorcerer had the misfortune of being released at a time when all the aspects of seventies filmmaking that had once made the decade so great and free were sadly being shunned and forgotten. Realistic, messy presentations of human emotions for adults to examine were no longer wanted. They were, and unfortunately still are now, by and large something for most film audiences to escape from and ignore.

Author Bio: Matt Hendricks is an independent filmmaker with several projects currently in development.