The Japanese cinema industry is one of the few industries that still has a huge impact on the world cinema, keeping its own brand and characteristics while adding several other genres and features that enrich their cinema even more. They didn’t show contentment and conformation to the classic; they maintain a very respectful in-view to the classic directors, actors, genres and movies, but they also added to that list a series of new directors and actors that become more and more famous, nationally and internationally.

This list tries to show the essential films of the Japanese industry, both classics and modern. I call your attention that there are NO ANIMES, I have to admit my ignorance towards that type of industry. I’m not a fan of Animes, although they are a big part of Japanese industry nowadays. I rather prefer to watch real actors with real emotions and real speeches, thus I decided not to include any Animes in this list.

Due to its diversity and continuous growth, several great movies had to be left out, and to compensate some of them I included some “Checks” at the end of some of the reviews to refer you to other great movies that could be included in this list. Also, the list was written with the intention of adding some diversity to the list, adding Samurai movies, but also comedy-movies, realistic dramas and crime/mystery movies.

NOTE: Only three movies per director were allowed, for that reason some movies of certain directors weren’t mentioned, just take a look at the chosen Kurosawa movies, for example.

40. The Family Game (Yoshimitsu Morita, 1983)

Although they aren’t present in great numbers here, the Japanese industry has its share of great comedies. “The Family Game” is a good example of that, transporting the viewer to a dysfunctional middle-class family trying to be as normal as they can, but never seeming to get ahold of that objective.

The connection as a family seems to break with the running of the plot, breaking down completely toward the end. Story-wise, the movie focuses its action on the academic success of the younger of the two sons of a couple. The objective to hire a tutor is to help Shigeyuki to raise his grades at school in order to enter the desired high school. That same tutor has a very important role, not only on Shigeyuki, but also on the rest of the family, being symbolic of the breakdown coming to them.

39. Youth of the Beast (Seijun Suzuki, 1967)

“Youth of the Beast” is one of those movies with fast-paced action and a plot very well designed, maintaining the suspense right until the end. It’s one of Suzuki’s finest releases and a personal favorite, in terms of mafia movies. It’s a yakuza movie, a Japanese mafia movie with lots of violence and some blood, with a great main character, Joji Mizuno, a former policeman who wants to avenge the death of his colleague and friend. Despite the fact that most yakuza movies are pretty predictable and are characterized for their excessive violence and graphic content, this movie escapes a bit from that.

“Youth of the Beast” has violence but I don’t consider it as graphic as most yakuza movies, which by itself adds a certain of “sophistication” and intelligence to a very well directed and acted movie. The plot is very well written and if you like classic Asian mafia movies, this movie is the one to watch and pay attention. There’s a twist in the end, which isn’t as easy to discover as many may think, at least for yakuza movies’ standards. Underrated classic!

38. The Burmese Harp (Kon Ichikawa, 1956)

Contrary to the grisly and gruesome account in which the Second World War is presented in the 1959 movie, “Nobi”, “The Burmese Harp” presents a much “softer” and “brighter” look into the life of the soldiers of a defeated Japanese army. It was considered one of the first movies to show a look from the Japanese army’s perspective. I agree that it’s a very bright and soft look into the life of the soldiers, with them singing all the time, but it symbolizes the hope and sentimental component of the war.

MIzushima is a private in the Japanese army; he plays the harp and takes it everywhere he and his company go. They sing and play together, which may symbolize that emotional and sentimental path of a group of men sick of the war and wanting to return home. After the Japanese unconditional surrender, a small group of Japanese soldiers is trying to fight on a mountain. Mizushima is called to convince them to surrender. The tribulations and sufferings he witnesses convince him to follow a different path of life, running away from everything that might remember him of such war.

The movie transports us to a sentiment of affection and camaraderie between the characters and rest of the company. Mizushima’s only egotistical feeling is when he steals a monk’s robe, with the intention of surviving and join the group, but that action is immediately repented with a feeling of altruistic will towards the victims of the war, after witnessing several dead bodies mounted into a pile.

That is something “Nobi” doesn’t present to us, that sentimental, altruistic and benevolent look of a soldier who is trying to survive, opposing the confrontational and almost disgusting point of view of an almost seemingly drunk soldier who is just trying to escape everything and sees several men commit the cruelest and soulless acts a human being can reach.

37. Early Summer (Yasujirô Ozu, 1951)

It’s another drama masterpiece by Ozu, released after “Late Spring” and before “Tokyo Story”, and it’s the second of the Noriko trilogy. It deals with family and relationships and the role of the women in a post-war Japan, which is evolving again into an economic power. Noriko lives happily as a young woman of a big family, when her uncle visit rushes her family to find her a husband.

Although nowadays this “quest” would be unacceptable and unethical, it wasn’t until some years that some of the husbands were found and chosen by the family of the young woman. Despite not being shown by Ozu as a criticism, it’s indeed a realistic account of post-war Japan that emphasizes the role of women in a growing Japan.

Check: another movie of Ozu’s genius, I Was Born, but… (1932), it’s one of the few comedies by Ozu that was later remade in 1959 in the movie directed also by Ozu, Good Morning. I Was Born, but… (1932) should have deserved a better spot on the list rather than just being mentioned like this, but Bakushû was preferred due to its depiction of a Japanese family after the war. Still, the 1932 movie is highly influential and very important for the Japanese movie industry. Also, I’d like to call your attention to the last Ozu movie, An Autumn Afternoon (1962).

36. Giants and Toys (Yasukô Masumara, 1958)

It’s the only comedy-drama on this list; I would say it’s a 50%-50% comedy and drama. It’s a very fast-paced movie where three major candy companies compete for better sales numbers. These companies are called World, Giant and Apollo. To make it funnier, three friends work in each of these companies and work in their respective publicity departments and, although being competitors, they discuss each company’s sales techniques and ideas on a prize to boost sales. The trouble starts when World hires a poor young woman, who is very pretty but has rotten teeth, in order to boost their sales and shake things up a bit in the business of candy competition.

The movie is also a drama, due to the fact that is a satire and a dramatization of the new industrial Japan, which in the late 50s and early 60s became more and more industrialized and a “battlefield” business-wise. It’s a huge critic to the workers’ dedication to their companies, wearing themselves into a state of almost sickness, or even major sickness.

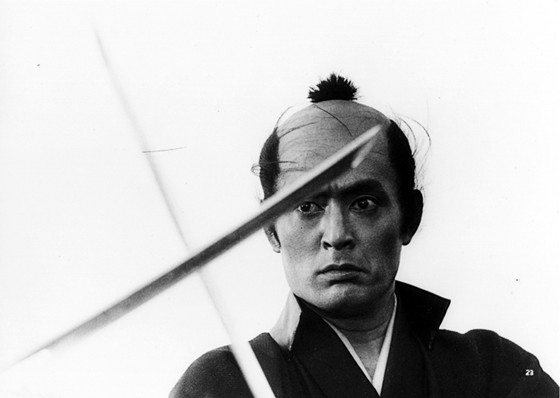

35. Samurai Rebellion (Masaki Kobayashi, 1967)

It’s another of Kobayashi’s homages to the bushido code and how the honor of a samurai is so well viewed in Japan. Kobayashi always had an emotional in-view towards the samurai’s code of honor and that continues in this release. Kobayashi cast two of the most prominent actors in Japan at the time, Toshiro Mifune and Tatsuya Nakadai, the latter having a less important role throughout the movie, but gaining importance in the end.

The Aisu clan lord is tired of one of his wives and mother of one of his children, Ichi, and wants her to marry the son of one of his vassals. Isaburo Sasahara’s son is the chosen one. In the beginning, the family is against this order from their lord, but they comply with it. In time, Ichi is well-received inside the family and Ichi and her husband, Isaburo’s son, end up loving each other. One of the lord’s sons dies and he is left with no heirs. The only heir left is the son he had with Ichi years earlier. Now the lord wants Ichi back along with their son, in order to have an heir. Isaburo’s son doesn’t want to return his wife; he loves her and had a child with her.

Its intense and the suspense is kept until the end. The fight scenes are kept for last, and although I’d say some of the fight scenes could be better choreographed, it really contains a high degree of intensity and anger, beautifully performed by Mifune’s brilliant acting.

The story goes against the typical feudal Japan, where everything the lord orders must be complied, otherwise the family would have serious and grave consequences, such as orders of hara-kiri or imprisonment. Nakadai’s role in this movie is more of a character who suffers those same consequences; he is a vassal of his lord and he has to comply to everything the lord orders, and despite his friendship with Isaburo, there’s a fight to the finish against his best friend.

34. Onibaba (Kaneto Shindô, 1964)

It’s the only horror movie included in this list, and although there are many doubts about its genre, “Onibaba” does include the necessary elements to be considered a horror movie. “Onibaba” is a deviation from the usual style of Kaneto Shindô, presenting much more visual features, contradicting his less impressive releases with a much less dynamic style of filming, while maintaining his usual themes such as sexuality and poverty. It’s the story of two women who survive by collecting the possessions from the soldiers they kill.

Both women may serve as symbolic for the women’s fight to survive during war times in 14th century Japan. Again, both are described as poor and kill soldiers to survive, despite the younger woman’s dislike. Neither of the women have names, which may also serve as another metaphor for the poor conditions most people lived in those days. The novelty of the plot is the appearance of a soldier who falls in love with the younger woman, but also the inclusion of paranormal features that affect the older woman and her “association” with the younger women, having daring consequences.

33. Twenty-Four Eyes (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1954)

It’s one of the most dramatic and emotional movies on this list, presenting the political change in Japan as background for the narrative. The movie explores themes such as childhood, politics, communism, war and affection. It’s a slow movie and you shouldn’t expect many twists and turns or an action-packed type of movie. It’s a very dramatic intent in which Kinoshita is able to make his finest and most emotional release, as it accompanies the lives of 12 first-graders and their young teacher.

This movie surprises presenting a plot with an 18-year time span, from the rise of Japanese nationalism and right-wing ideas (1928) to the beginning of the peace era, Shōwa era, after the defeat in the Second World War and the beginning of the Japanese economic miracle, social and political reforms (1946).

The future of the children is Kinoshita’s main concern, symbolizing that same concern through his main character, Hisako Ōishi, a young teacher who is beginning her teachings. The 12 kids will become her most representative class and will make a very strong impression in her life, accompanying her concerns on the dubious future they might have in a Japan with political instability.

32. Humanity and Paper Balloons (Sadao Yamanaka, 1937)

The 1937 classic movie is still one of Japan’s biggest influences on what would be the legendary era of Kurosawa, Ozu, Teshigahara, Kobayashi and Ichikawa, and many others. It follows the lives of the poorest people in a supposedly civilized Japan. It’s also a major critic on the poor conditions that people living in slums had and their fight to survive. I admit the movie isn’t extraordinarily produced, but considering the means in which was filmed the job done was exquisite, to say the least.

It follows the lives of a group of people in a Japanese slum, but it mainly accompanies the lives of two characters, Shinza and Unno. The first is a hairdresser but also a con-man who likes to organize gambling parties in his house, which goes against the slum leaders, who are gangsters and control the slum in an autocratic fashion; the latter is a masterless ronin, which by the 18th century was considered as a great dishonor for samurai Japan.

The performances are actually pretty good, and despite its production, we have to consider the date the movie was released, which was 1937. The Japanese cinema was only then getting acquainted and getting famous internationally, but also we have to consider the political era in which Japan was involved. Japan, in 1937, was a right-winged and nationalistic country which limited how movies were made, thus limiting the directors’ creativity. Still, this movie was able to release and spread a sense of national awareness to the poor conditions people in slums had, and to make a social criticism of its country that could be transported to those days of the 1930s in Japan.

Check by the same director another classic, Sazen Tange and the Pot Worth a Million Ryo (1935), a funny comedy with its dramatic moments and an essential of Japanese cinema.

31. Love and Honor (Yôji Yamada, 2006)

It’s the final episode of the acclaimed trilogy by Yôji Yamada, after “The Twilight Samurai” (2002) and “The Hidden Blade” (2004). It tells the story of a low-class samurai who is a food-taster and turns blind after tasting one of his Lordship’s dishes. In order not to lose his status in the castle and his stipend, his wife must provide certain favors to a high-class samurai, without her husband knowing anything about it.

The movie is a great representation of its title, “Love and Honor,” where love is represented by the couple’s love and honor by the vengeance perpetrated by the husband against the high-class samurai. From the trilogy, this release is perhaps the most polished and refined, both in terms of plot and production. Of the three movies, it’s the best written one, and despite its plot not being defined for its complexity and creativity, it does provide a great perspective of the samurai code of honor and struggle to survive in a Japan from the Edo period. It was a very emotional release and a great ending to a definitive trilogy.

“Love and Honor” has the ability to build expectations and provide a fresh look to a samurai society, without getting boring or too squeamish, involving the viewer in the plot with the running of the narrative.