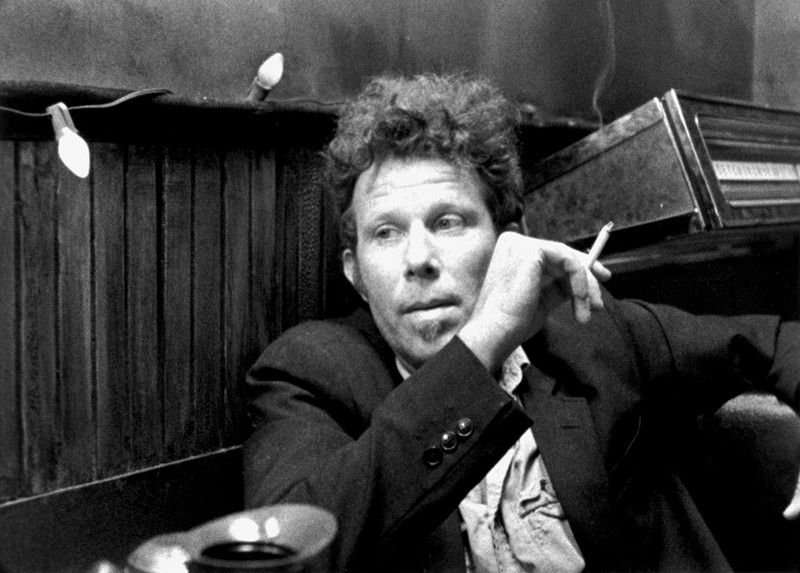

Since the 70’s, Tom Waits has established himself as a phenomenally unique and gifted performer. Beginning as more of a singer/songwriter, he became a poet of the gutter and seedy bar, as well as a perpetuator of both the classic Americana song tradition and that of the German music hall, in stylings of Kurt Weill and such. His music escapes genre confines, while his raspy, cigar-and-bourbon soaked voice is never forgotten once heard.

Since the late 70’s, he’s also been appearing in movies, both as an actor and composer. With time, Waits has established himself as a king of the cameo and the episode. He rarely lands a leading part (despite his boast in “Goin’ Out West”-“I ain’t no extra, baby/I’m a leading man”), but never fails to make an impression.

Only part of that is the carryover effect from music. To his parts, no matter how small, Tom brings his uniqueness, resulting in a rewarding experience. Though perhaps too odd and singular to be a true movie star, Tom is one of the few rock stars who managed to achieve a steady and successful film career.

This list explores Tom’s contributions to cinema. The entries were included based on how interesting they are, either on their own or with Tom’s help. Some real oddballs, whose claim to relevance is Tom’s presence, are left out, as are Coppola’s Twixt and Jack Nicholson’s Two Jakes (a failed sequel to Chinatown).

Special attention is given to Tom’s musical contributions to cinema, and the times where his songs are used to the best effect on the soundtracks are listed here as Tom’s gems.

1. Paradise Alley (Sylvester Stallone, 1978). Soundtrack, actor.

Tom’s cinematic beginning can be considered modest. Paradise Alley is not a very good film-for the very obvious reasons that Stallone is not a very good director or writer. It has all the potential of a cult classic, and realizes almost none of it. This is Rocky meets Rocco and His Brothers, a wrestling melodrama set in the 1946 Hell’s Kitchen. Three brothers-a hustler, a wounded war veteran, and a slow-witted lug-try to make it out of the hellish neighborhood.

As said earlier, the writing is often incoherent, the story pulverizes itself in the las fifteen minutes, and the dialogues between characters sound like Sly talking to himself, pace-wise. But there are rewards.

Sly was prudent enough to engage the services of a gifted cinematographer Laszlo Kovacs, and the well-presented atmosphere is the best thing about the movie. Some scenes also stand out, particularly the wrestling bout in the rain and hungover Stallone chasing cockroaches with a Louisville Slugger. Several one-liners are memorable.

Armand Assante as the middle brother easily outshines everyone else, Stallone included, while the use of actual veteran wrestlers adds to the authentic feel. And then, of course, there is Tom. By own admission in a famed interview on an Australian talk show, “For me, it was a five-week shoot for three lines of dialogue”. But his character, a lounge pianist named Mumbles, perfectly belongs in the smoky bar.

Also, Waits wrote and performed two songs specifically for this movie-“(Meet Me in) Paradise Alley” and “Annie’s Back in Town”, which he never released on any of his albums, giving Paradise Alley additional worth, and marking the first time his songs were used on a motion picture soundtrack. In all, a small debut, but nothing to be ashamed of.

2. Tom Waits for No One (John Lamb, 1979). Song, performer.

Preceding Ralph Bakshi’s “American Pop” and Richard Linklater’s “Waking Life”, this seldom-seen curio reemerged with the advent of the internet. And thankfully so-it’s 6 minutes of visual and musical joy. A hybrid between an animated short and a music video, it features Tom captured and re-imagined with an aid of exciting new technology.

The director, John Lamb, together with Bruce Lyon, has just invented and patented the Lyon Lamb Video Animation System, a single-frame reel-to-reel video recorder with the unique capability to play back at film speed (24 fps).

Although the rotoscope was invented as far back as 1918 by Max Fleischer, this new device allowed for an immediate viewing of the pencil test, thus saving much time. Lamb filmed Tom and an actress live on a soundstage, and then traced with the new system and animated.

The story is simple-Tom, a care-free knockabout on a smoky night street, conjures up a curvaceous brunette beauty from the smoke of his cigarette, who flirts with him and performs a striptease act set to him reciting a version of his jazzy, bass-drive “The One That Got Away” from the “Small Change” album.

Though he tries to woo her with his jive talk and song, she ends up driving away in a big shiny limousine, leaving Tom to philosophically shrug-“Win some, lose some.” Overall, it’s a feast of forms, shapes, and music.

Its experimental nature drew top talent, in addition to Waits, to work on it (David Silverman, the first animator of “The Simpsons”, was the main animator here). The whole endeavor helped Lamb to receive an Academy Award for Scientific and Technological Achievement, and became an industry calling card for the new system.

Tom gem: “Invitation to the Blues”. Appears in-“Bad Timing”. Nicolas Roeg used this melancholy number in the opening sequence of his controversial film, and it did a fine job of setting the mood for the catatonic ennui that was to unfold on the screen.

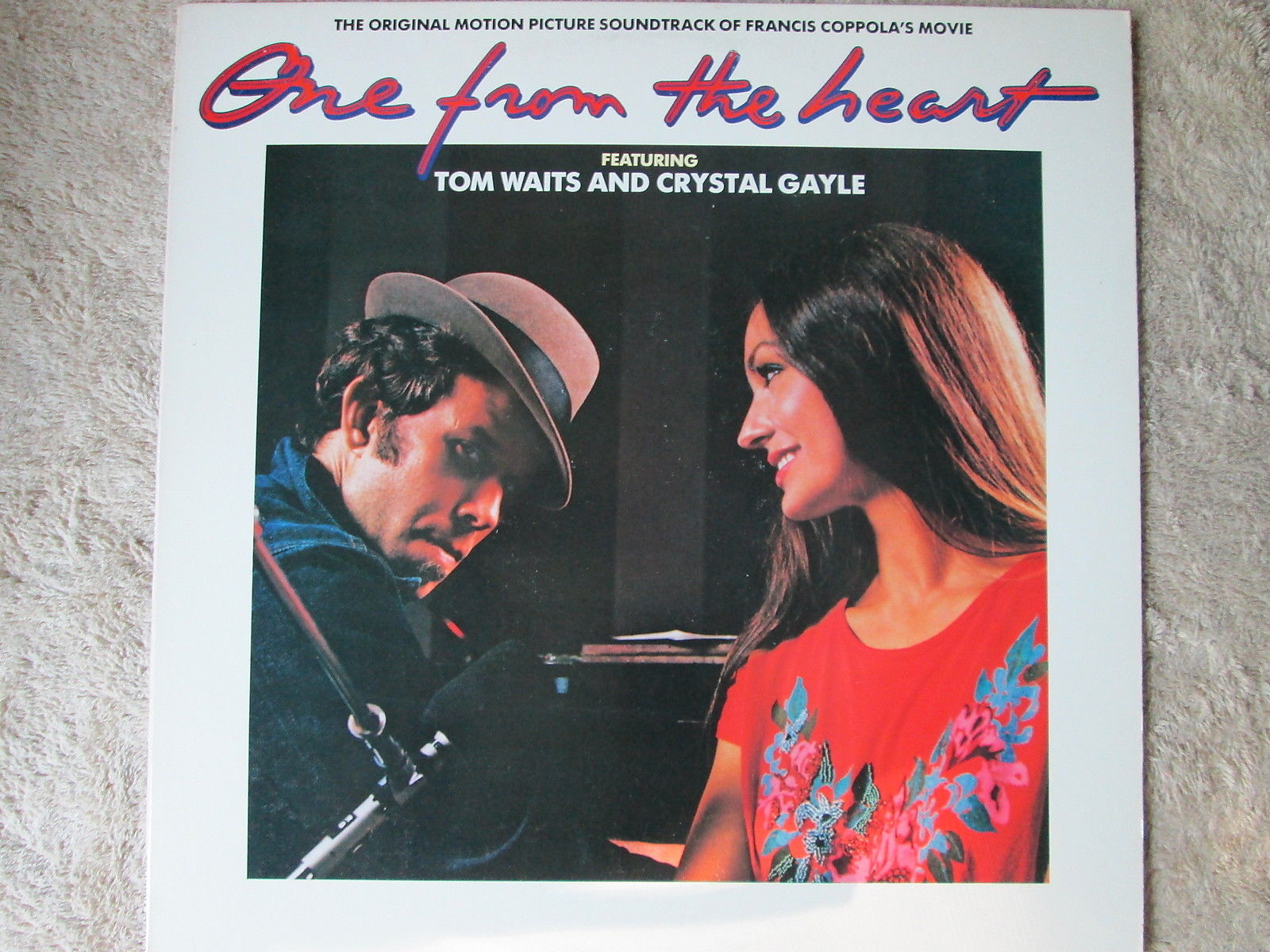

3. One From the Heart (Francis Ford Coppola, 1981). Composer, cameo.

A vital production in both Tom’s and Coppola’s lives. By 1980, Waits was in the state of funk, reeling from a bad breakup, lukewarm public reception of his previous album, and the monotony of touring. Francis Ford Coppola has finished the incredible physical and psychological ordeal of making Apocalypse Now. Having gone from the hell of location shooting and delving deep into the chasm of human darkness,

Coppola wanted to sort of go back in time and make a movie in the controlled set environment, with a Hollywood-happy ending. He came up with a spectacular failure. The budget quickly ballooned from 2 to 26 million, not even one of which was recovered by the box office. It spelled an end of Coppola’s creative freedom-for a long time afterwards, he was forced to take on projects just for money. But it’s an amazing-looking failure with many little rewards.

The cinematography of Vittorio Storaro is nothing short of spectacular, as is the fantastic set design by Dean Tavoularis (who managed to create Las Vegas on the soundstage). Though the lead performances of Frederic Forrest and Teri Garr often come across as flat and over the top, the supporting cast includes Raul Julia, Nasstasja Kinski, Lainie Kazan, and Harry Dean Stanton, each of whom made the most of their screen time.

And then there is Waits’s score, for which he received an Oscar nomination. Coppola got Waits on board because of Tom’s loungy 70’s songs, and Tom rose up to the challenge of providing a necessary atmosphere for this shiny, artificial world. He did write the duet numbers with Rickie Lee Jones in mind, but due to their recent breakup, she turned down the offer. Negotiations also failed with Bette Midler, so for female vocals, Coppola and Waits went with Crystal Gayle.

Although she has a very pleasant and silvery soprano, her delivery was more honky-tonk and country rather than jazzy and lounge. The best numbers on the soundtrack are Waits’s solos, especially the haunting Broken Bicycles, as well as the jazzy numbers Little Boy Blue and You Can’t Unring the Bell. Tom also made a blink-and-you-miss-him cameo appearance as a trumpet player in the club band.

And although the project turned out to be disastrous for Coppola, Tom seemed to thrive in the more controlled environment of writing music for a specific purpose (“It was good for me, it disciplined me, it made me-I had to sit in a little room and they’d ring me up on the phone and put memos under my door-it was like working in an office.

Builds character, I think the lock was on the outside of the door, not the inside, they were afraid I was gonna go to Acapulco.”), and also me this current wife Kathleen Brennan on the set of the movie (she was employed by Coppola’s Zoetrope Studios), establishing a relationship that would prove incredibly rewarding for him, both personally and artistically.

4. Outsiders/Rumble Fish (Francis Ford Coppola, 1983). Actor (episode).

Coppola must have liked the experience of working with Tom. In 1983, he directed a sort of dilogy, two adaptations of S.E. Hinton’s novels, with mostly the same cast and crew.

The dramatic Outsiders is better known, as it introduced a whole platoon of young actors (Patrick Swayze, C. Thomas Howell, Matt Dillon, Ralph Macchio, Diane Lane, Rob Lowe, Tom Cruise, Emilio Estevez-take a pick!), while the black-and-white Rumble Fish is much more impressionistic, focusing on the relationship between two brothers (excellent turns by Matt Dillon and Mickey Rourke).

Both are set in Tulsa, and are about the existential struggle of life’s “outsiders”. Waits makes brief appearances in both. Very brief in Outsiders, portraying the red-light dive’s doorman Buck Merrill (“I had one line-‘What is it you boys want?’ I still have it down if they need me to go back and re-create it for any reason.”).

In Rumble Fish, he gets a bit more screen time, playing a well-cast role of Bennie the pool hall owner. Coppola let Tom have considerable input, allowing him to pick his own costume and write his own dialogue, correctly guessing that no one can write a better Waitsian jive than Waits himself. The jazzy delivery of the monologue on passing time, where Bennie is shot from above in a skewed angle, is fun and memorable.

Tom gem: “Ruby’s Arms”. Appears in-“First Name: Carmen”. Jean-Luc Godard was another filmmaking great that instinctively got how atmospheric Tom’s songs are, and how they help in setting the mood. For a Frenchman, Godard does have an excellent ear for English lyrics, as he also used Leonard Cohen’s songs to great effect.

5. Streetwise (Martin Bell, 1984). Soundtrack.

Although many of Waits’s songs are about the gutters of society, it’s not often that he makes a direct social commentary. Usually, his style is lyrical narrative of the downtrodden.

Occasionally, though, he makes a direct appeal, notably in songs like “The Fall of Troy” (dealing with child murders) and “Road to Peace” (Israeli/Arab conflict). He somewhat does it here too. Martin Bell and his wife Mary Ellen Clark made a deeply affecting and harrowing documentary on the homeless children of Seattle, originating from the Life magazine story “Streets of Lost”.

In the middle of Reaganomics and the rise of the yuppies, Bell shows an underbelly of America, focusing on the orphans or runaways who were left to fend for themselves. In the middle of the prosperous Seattle, with its booming industry and beautiful ports, these kids live in abandoned buildings, panhandling and prostituting themselves to earn money for their food and drugs.

Especially vulnerable are the young dumpster diver Rat and a teenage waif of a prostitute Tiny. Bell and Clark opt to not moralize or punch the sad moments up with mood music-they just let the kids speak for themselves, training the camera on the protagonists and their surroundings. Waits’s contributions are the musical bookends-opening titles roll to the “Rat’s Theme” whistle, while closing credits-to him performing his song “Take Care of All My Children” (available on the “Orphans” album).

Besides that, the only music in the film are the diegetic sounds from the blaring boomboxes and radios, and a couple of street performances by the inimitable busker Baby Gramps of “The Teddy Bears’ Picnic”. Tom’s musical contributions effectively set the mood and provide almost a pleading message that reinforces the humane message of the film.

6. The Cotton Club (Francis Ford Coppola, 1984). Cameo.

The description of the troubles this production faced deserves a book of its own. Robert Evans brought Francis Ford Coppola on at the last moment, and with several dozens (!) versions of the script. It’s a given that when your primary sponsors are Italian mobsters and Arab gun dealers you’ll be wise to watch your back. Coppola was lured by a large salary, still reeling from the losses incurred by One From the Heart.

As a result, this period piece about the eponymous Harlem jazz club is a masterpiece that never happened (and sustained a huge financial loss). Coppola and Puzo failed to create another Godfather, as Evans had hoped. Waits was cast as Irving Starck, a perennially cigar-chewing manager of the club, but for him the experience amounted to more or less standing in costume and chewing on a cigar in a tux. For months. Waits describes the experience as “being Shanghaied”.

In the end, only about a dozen of his lines made the final cut (though he did deliver some of them through the bullhorn, a practice he would often repeat at his concerts). He did make a good friend in the person of his fellow actor Fred Gwynne (famous for playing Herman Munster on TV).

But for him the experience was a dud. He should consider himself lucky, though-Coppola ended up being threatened by the mob, and Roy Radin, a vaudeville promoter and one of the driving forces behind the making of the film-killed outright, while the box-office was incredibly disappointing.

Shame-despite the script mess, Coppola has made a gorgeous-looking film with a killer soundtrack, and, although lagging in story at times, some great acting turns (particularly James Remar as “Dutch” Schultz and Bob Hoskins as Owney Madden). The rest of names in the cast reads as Who’s Who, with many making their debuts-Richard Gere, Diane Lane, Gregory Hines, Nicolas Cage, Julian Beck, Laurence Fishburne, Jennifer Grey, Joe Dallesandro-you name them, it has them.

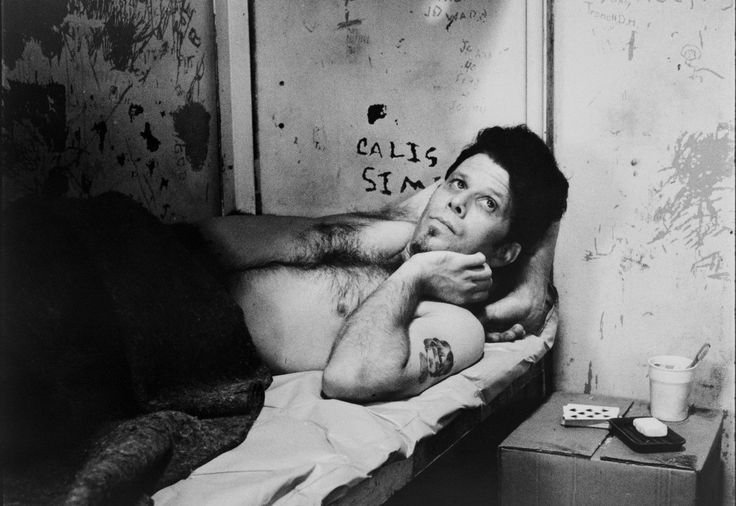

7. Down by Law (Jim Jarmusch, 1986). Actor, soundtrack.

A superb and one-of-a-kind minimalist journey of a film. “It’s a sad and beautiful world”, exclaims one of the main characters, and Jarmusch unobtrusively shows us why.

For Waits, it presented a new challenge-a leading role. His low-key approach works perfectly here, as he portrays a DJ who is wrongfully imprisoned and thrown into a prison cell with equally sullen and wrongfully jailed John Lurie’s pimp, and Roberto Benigni’s eternally cheerful and positive Italian tourist.

The Americans growl and bicker at each other, but Roberto’s endlessly positive attitude and a seemingly magical ability to procure food serves as an adhesive for the trio as they escape across the Louisiana swamps.

Filmed in luminous and silvery black-and-white by frequent Wenders cinematographer Robby Muller, the film is a visual and aural delight. The presence of two outstanding musicians as main heroes ensures the quality of the soundtrack.

John Lurie’s lounge and jazzy numbers provide the main music for the film, but two of Tom’s songs from his seminal “Rain Dogs” album-“Jockey Full of Bourbon” and “Tango Till They’re Sore”-again serve as effective bookends, played over the opening titles and closing credits. “Jockey” is particularly effective, as it backs the stunning opening sequence of Muller’s camera panning and tracking across the decaying New Orleans landscape, the best opening since Orson Welles’s “Touch of Evil”.

8. Ironweed (Hector Babenco, 1987). Actor.

Tom definitely ended up in a good company here. Both Jack Nicholson and Meryl Streep got Oscar nominations for their turns in this adaptation of William Kennedy’s Depression-era novel. Argentine-born Hector Babenco, fresh off his one-two successes of Pixote and The Kiss of the Spider Woman, presents a compelling slice of Americana, aided, doubtless, by his outsider perspective.

Nicholson and Streep elicit both fascination and sympathy as a pair of drunks in upstate N.Y., and both sink their teeth into the roles as Babenco masterfully utilizes poetic realism to present Francis Phelan’s debilitating memories and Helen Archer’s melancholic and disjointed flights of drunken imagination. Unfortunately, the film was a commercial failure, barely returning a quarter of its budget.

It may have had a chance of being a hit in the 70’s, at the height of Easy Riders/Raging Bulls movement, but the Reaganomics and Thatcherism of the late 80’s created an atmosphere where gritty poetics had no place. Tom’s role as a drifter named Rudy was not large, but he more than held his own when paired with Nicholson, who was in his prime (Tom commented that acting opposite of Jack was similar to trying to catch bullets with your teeth).

And the experience proved positive for Tom, as he befriended many of his fellow actors, and made a particularly close connection with William Kennedy, the screenwriter and author of the source novel. They even collaborated on the writing of a song for the film, “Poor Little Lamb”, a full version of which would only appear about 20 years later on the “Orphans” album (it will be mentioned often in this list, and is highly recommended for fans of Waits in particular and great music in general).

Though not a perfect film (two-plus hours of minimalism always seem like about four), it’s a worthy addition to everyone’s filmographies (it also features Carrol Baker, Tom’s Cotton Club co-actor Fred Gwynne, and a very young Nathan Lane making his acting debut).