Ordinary People over Raging Bull. How Green Was My Valley over Citizen Kane. Spotlight over Mad Max: Fury Road (seriously, but that’s for another list). It’s not news that the Oscars often make decisions that some consider to be… a little wide of the mark. Again and again, films held to be classics have been overlooked. But at least they received some recognition, all be it in the form of nominations or wins in other categories.

But many great films go completely unrecognised. Films that depict life in all its beauty and ugliness. And maybe this is where they go wrong for the Academy – the truth can hurt, and the Oscars are meant to be a party.

The following movies are today generally accepted as classics. None of them are little known pieces that you’ve probably never heard of (apart perhaps from the last one). The point of this list is simply to remind ourselves that the Oscars aren’t the last say in what’s good and what’s not.

“Well of course I already know that,” you might be thinking. But if, for example, La La Land had not received the recognition that only the Oscars can bestow, would we still talk about it today? Regardless of your opinion of it, it’s important to remember that La La Land, having been blessed with Oscar gold, became part of the cultural conversation; lots of people went to see it and talked about it simply because the Academy nominated it.

And that discussion cuts both ways – La La Land was probably going to win Best Picture before Hollywood noticed some people thought they were racist, which means that a film like Moonlight gets nominated and so the conversation shifts, hopefully for the better.

The criteria for these choices, listed chronologically, is that they all came out after 1927 (the first Oscars ceremony in 1929 was for films that came out in the two preceding years), and they did not receive a nomination in any category.

In the meantime, hands up who’s seen How Green Was My Valley…?

1. M (1931)

When your last couple of films are deemed expensive flops (including Metropolis, a favourite of Hitler and Goebbels), the subjects of paedophilia and infanticide aren’t what most people would look upon as potentially commercial material, but that’s exactly what Fritz Lang did. He chose to tell a story inspired by real life serial killers whom he met in a mental institution as part of his research for the movie that would become M.

Peter Lorre plays Hans Beckert, a molester and murderer of children. As the police try to catch him, Lang shows us how the entire city is affected, using Beckert’s psychosis as a key to unlocking the psychosis that lies within society and is perhaps even more dangerous.

We witness scenes in everyday environments, such as on a tram where a crowd of people stoked up on press-fed paranoia turn on a man that someone wrongly fears is the killer. Eventually press and political pressure lead to the police cracking down on all criminal activity in a hope that Beckert will be caught in their far flung net. As a result, the crooks decide to protect their own interests by setting out to capture Beckert themselves.

As the film goes on, Lang delves deeper by forcing the audience to at least try to understand our anti-hero’s tortured state of mind. Beckert argues that other criminals choose to break the law, whereas he is a helpless victim to his impulses.

Lorre’s wide-eyed, almost childlike performance as a man begging for his life is a larger-than-life turn, but in the best way, like Daniel Day-Lewis in There Will Be Blood or Jack Nicholson in The Shining. It’s also, for better and worse, the role that would shape his future career in films such as The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca.

And yet this masterpiece received no recognition from the Academy. Admittedly the Oscars were only a few years old and, like it or not, non-English language films don’t get nearly as much recognition, especially in the Best Picture category. To date there have been only 10 non-English language films nominated for the top award – and one of those was Life is Beautiful!

But it is also true that the Academy can be easily turned off by “difficult” material. There is, however, no doubt that today M is still a brilliant and disturbing experience.

2. Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949)

The music journalist Miranda Sawyer suggested that she knew the midlife crisis was a real phenomenon because the Brits joke about it, which means Kind Hearts and Coronets must be one of the more truthful depictions of Britain’s class system, being as it’s one of the funniest films the country ever produced.

Dennis Price is Louis, a man in line to inherit the D’Ascoyne dukedom. Ninth in line to be exact. And so he decides to take the simplest course of action to ensure he gains what he sees as his rightful place: he will kill each and every one of the eight relatives who lie between himself and the Dukedom of Chalfont. The fact that they spurned his mother after she married “beneath her” and then refused to bury her body in the D’Ascoyne family crypt makes it all the easier for Louis to remain the epitome of cool elegance as he offs them in highly inventive ways.

The eight D’Ascoynes that Louis has in his sights are all played by Alec Guinness. Partly a sly dig at the inbreeding of ancient dynasties, it also allowed the actor to showcase his chameleonic talents. Unfortunately not even this flashy performance gained the Academy’s attention, despite them years later nominating Peter Sellers when he played three characters in Dr. Strangelove.

Kind Hearts and Coronets is the story of a serial killer (though he isn’t one who, like M’s Beckert, is slave to his tortured soul – Louis has a specific list of targets in mind) that handles its satiric tale with delightful wit. Louis is presented as a man perhaps more naturally to the manor born than any of his victims. The film’s suggestion that his effectiveness as a murderer might just confirm his suitability to the life of a duke is just another part of what makes this film as delicious as the caviar one of Louis’s unfortunate relatives tucks into with explosive results.

3. Sweet Smell of Success (1957)

Kind Hearts and Coronets was an Ealing comedy directed by Robert Hamer. Another great director to come from that English studio was Alexander Mackendrick who, after making some of Ealing’s greatest pictures – The Man in the White Suit, The Ladykillers, Whisky Galore! – went to America and helmed Sweet Smell of Success.

This is a film of such scripted brilliance, perfect black-and-white cinematography and skilful direction that it seems impossible it should have completely fallen off the Academy’s radar. What didn’t help was that it flopped at the box office.

Tony Curtis is Sidney Falco, a press agent desperate to get on the good side of Burt Lancaster’s columnist J.J. Hunsecker. Hunsecker has a near incestuous obsession for his younger sister Susie (played by Susan Harrison) and has no qualms about using Sidney to break off Susie’s relationship with a jazz musician.

In all honesty the plot is not the most interesting thing about this film. It’s the dialogue, a lot of which was written on the day by playwright Clifford Odets. He would reel off pages of script, which Mackendrick and the actors would work on to cut down, essentially performing the next step of rewriting that Odets didn’t have time to do himself.

The film doesn’t just portray one of the all-time great love-hate relationships between Hunsecker and Falco, it’s also one of the more subtle and satiric dissections of Broadway and, by extension, Hollywood. At one point, in an almost throwaway exchange, Hunsecker asks a cop if he knows anything about a woman who recently attempted suicide. After checking via his radio, the reply comes:

COP: She died twenty minutes ago.

HUNSECKER: That’s show business.

It seems digs at Hollywood’s expense are fine until they start drawing blood.

Aaron Sorkin says that for him dialogue is music. Sweet Smell of Success’s words feel like the best jazz – alive, fresh, beautiful and dangerous, as well as something that could only have come from America.

4. Breathless (1960)

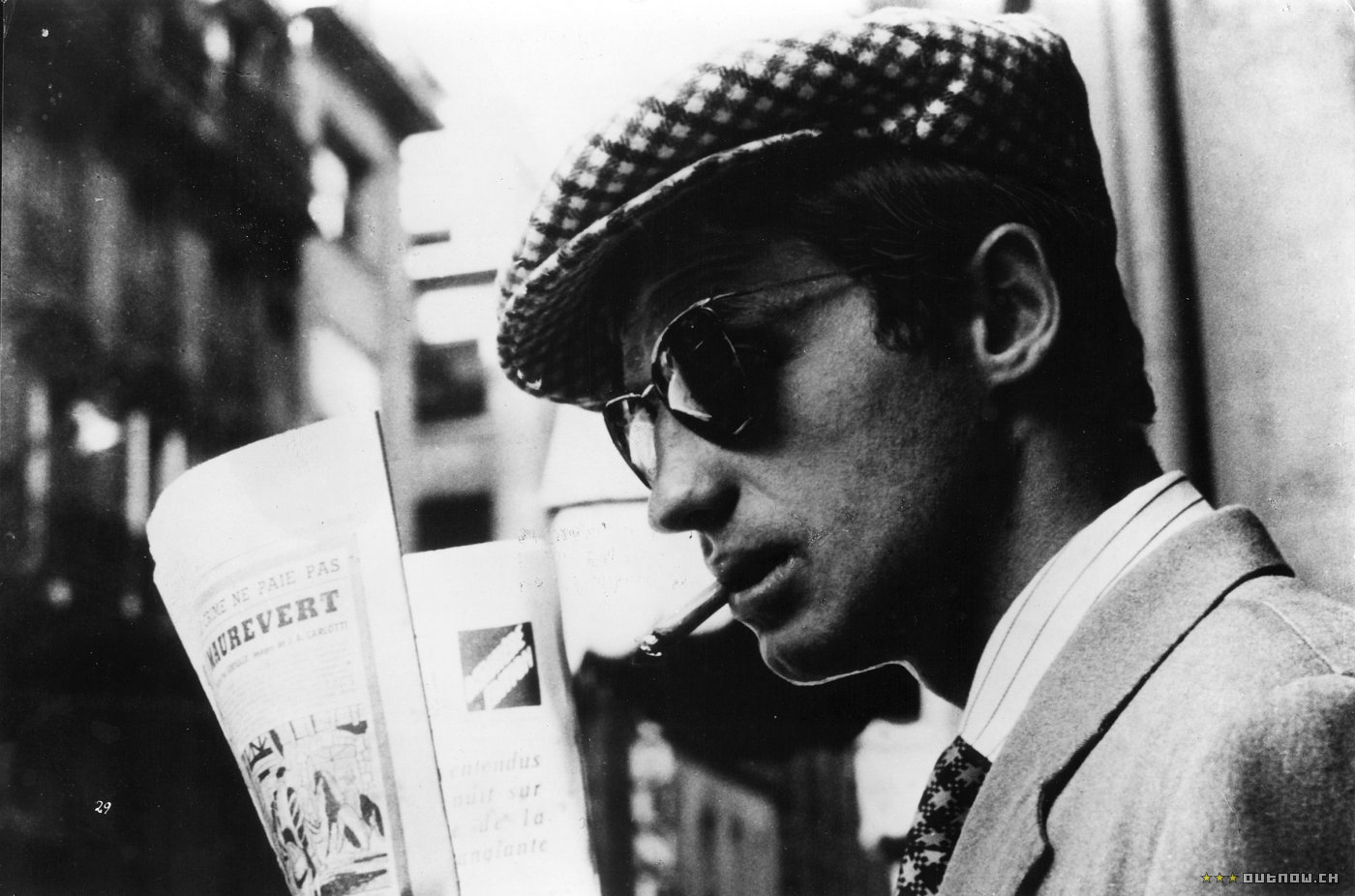

Breathless was a huge success when it came out and, as typical of its director Jean-Luc Godard and many of the French New Wave filmmakers, contained plenty of references to cinema, particularly Hollywood. (Godard later had Fritz Lang play himself in Le Mépris). Jean-Paul Belmondo plays Michel, a guy who isn’t just a small time gangster, he’s a gangster who models himself on Humphrey Bogart. It isn’t enough to be something, he also has to play the part. But isn’t that what we all do since we started watching movies?

Michel steals a car and is pulled over by a police officer. In a panic, he shoots the officer using a gun he finds in the glove box and goes on the run. This is no longer a fantasy – it’s for real. Except it isn’t because this is a film, something Godard constantly reminds us of throughout.

One of the most influential and important films ever made, Breathless tore up the rule book in too many ways to go into here. Just one example: partly as a result of the necessity to cut its initial running time from two and a quarter hours to a tighter 90 minutes, Godard almost casually cut chunks from some of his long takes and created something we see used today so regularly that it’s not noticed any more – the jump cut.

Godard was the Tarantino of the 1960s in his use of popular genres, hip attitude and pop cultural citations. He would go on to achieve much more in cinema over the coming years, but Breathless was that rare thing that every wannabe filmmaker dreams of: a smash debut.

Again, a foreign language film isn’t going to have much chance of grabbing the Academy’s attention, especially when the rules state countries may only submit one film for consideration. But often it takes time for the rest of the world to catch up when something truly different comes along. The originality of Breathless is proven by how we now take everything it did completely for granted.

5. Don’t Look Now (1973)

What’s the first thing you want to do when someone utters the words, “Don’t look now…”?

But there’s a difference between looking and seeing, and it’s the latter that Nicolas Roeg’s masterpiece demands of the audience. A film in which the characters are constantly trying to see and understand the mysterious images presented to both them and us.

The film opens with the accidental death of a young girl. Her parents Laura (Julie Christie) and John (Donald Sutherland) go to Venice, partly for a job he takes there restoring a church, but also to help them recover from their trauma.

Laura is told by a blind medium that she can see her daughter’s spirit and that she’s happy. This cheers Laura, but John dismisses it as nonsense. He would rather believe the evidence of his own eyes, but it’s one thing to look at a figure in a red coat (like the one his daughter wore when she died) that he notices running away, and another to work out what it is he is really seeing. Is it really the ghost of his daughter?

The film is categorised as belonging to the horror genre, but viewers will be disappointed if they’re expecting The Venetian Chainsaw Massacre. More accurately this might be seen as a drama about a couple both blinded by their pain.

If the Academy had seen it as such then they might have found room for it that year. After all, the Academy aren’t too fond of horror, having only ever once given the Best Picture prize to a film from that genre, The Silence of the Lambs.

But not only is Don’t Look Now worthy of Best Picture, it stands out in the acting, script, direction, cinematography, sound and editing, which all come together to create something more than just a film for us to look at – this is a film to be experienced, as long as you try to see…