5. The New York Ripper

A hugely divisive film among Fulci fans, it is regarded as a return to more familiar giallo territory after his more recent excursions into the realm of outright horror where he fully established himself as the “Godfather of Gore”. In truth, The New York Ripper was an exploitation piece as the US film industry was finally following in the footsteps of Italy’s finest horror-thrillers leading to the creation of the slasher flick which was seeing an enormous boom there, and this was Fulci’s way of quickly cashing in on that.

The film has seen some tremendous amount of criticism for being misogynistic, but this claim is a tad preposterous, sure the killer targets attractive young women (and his reasons for doing so are ridiculous), but women have generally always been the target of killers throughout both the giallo and slasher film movements, so such notions should best be ignored.

New York in the 1980’s was at boiling point; violence and crime were everyday occurrences and poverty was rife. It would have been an ideal setting for a serial killer flick in which the killer’s motivations were driven by social inequality, and perhaps, to some extent, that was at the back of Fulci’s mind when he created this bleak slasher film.

A depraved killer who speaks with a Donald Duck voice (a throwback to the brilliant Don’t Torture a Duckling) is brutally murdering attractive women across the city, which sees Lt. Fred Williams (Jack Hedley) assigned to the case, he teams up with psychoanalyst Dr Paul Davis (Paolo Malco) to find the killer.

Several blatant red herrings and numerous brutal murders later, they uncover the true identity of the killer and explain his rather ridiculous reasons for him being what he is. Of course, narrative hasn’t exactly been a consistent strong point with Fulci, but The New York Ripper might actually represent an all-time low, well, at least up until this particular point in his career.

The level of violence seen on display here is a cut above (pun intended) the rest of its contemporaries, with Fulci seemingly determined to show every minute detail of his killings, so don’t expect him to cut away from any of his lengthy torture scenes. His bloody fascination goes some way to understanding why The New York Ripper has still never been released uncut in the UK and the reaction that the film has received in general.

Evidently, Fulci was going all-out to outdo the likes of John Carpenter’s Halloween and William Lustig’s Maniac in terms of shocks and gore, though in doing so he neglected to add any tension to the film, its 1970’s porno-like score helping little in this area either.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of it, though even this is perhaps not fully developed either, is that the New York depicted here is a cesspit of corruption and perversion, even the protagonists are not without their flaws and deviations. It’d be nice to see this as a piece of social commentary, and perhaps it tries to be, but without more input from co-screenwriter Dardano Sachetti – who would not work with Fulci again after this – the film simply falls flat.

There are a wealth of sub-plots that remain undeveloped and overall, it’s certainly not one of the director’s greatest efforts from a technical standpoint, yet its undeniably a curiosity of sorts, it marked the moment that his career took a sharp downward turn and yet still, it’s certainly worth a look that’s for sure.

4. The Psychic

A highlight from Fulci’s career, of that there can be doubt, The Psychic is a fine giallo thriller whose opening shows us the film’s protagonist as a child, superbly setting the tone for what is to follow, whilst introducing us to the gift that will ultimately serve as both her captor and emancipator. It’s not as violent as one might expect from a Fulci film, but it’s a smart, superbly paced thriller, full of beautiful, haunting cinematography and some sublime work from composer, Fabio Frizzi.

As with so many gialli releases, The Psychic features a narrative that concerns a man accused of a crime that he did not commit, but in this instance, the only person who can clear his name is his clairvoyant wife, Virginia (played by Jennifer O’Neill).

For her, her gift has been seldom more than a curse, firstly haunting her as a youngster before moving forward twenty years to the discovery of the body that could see her husband, Francesco, incarcerated (it’s his missing ex-girlfriend). The narrative builds slowly and methodically instead of relying on cheap thrills and gore, ultimately delivering both a thrilling finale and a rather fine, elegiac soundtrack that might sound familiar to fans of Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill.

Throughout the film Virginia is forced to argue the case for her own sanity as she is constantly put down and mocked, yet still she fights on. Few would ever consider arguing the case for Fulci as a proponent of feminism, yet there can be no denying that The Psychic is surely an inherently feminist piece, with the courage and inner strength of Virginia overcoming the patriarchal hegemony that surrounds her.

Power and wealth amount to very little in this film, paling into insignificance next to Virginia’s insight, her ability to act in a reasoned manner sees her through whatever the violent, male dominated world can throw at her. The Psychic is assuredly one of the most intelligent and mature films that Fulci ever made, making it a must-see movie.

3. Don’t Torture a Duckling

Arguably the finest film that the Italian maestro ever made, Don’t Torture a Duckling is a truly sublime giallo thriller that finds Fulci creating a statement of social and moral concern that does not paint a particularly flattering image of the catholic church.

It was a particularly daring film for 1972, violent and ambitious it provides startling insight into Italy’s small-town politics and questions the standing of both the church as a whole and that of the more local gentry who invariably have such high standing within their communities. Catholicism, from the outside, appears to be built almost exclusively upon the notions of sin and guilt, and here, they form the backbone of the narrative structure, even giving us an understanding of the killer’s motives which aren’t quite as dark as one might expect.

Set in the sleepy little hamlet of Accendura, a close-knit community is shocked to the core when young boys start getting bumped off, and the superstitious populace quickly proportions blame to a variety of their less desirable members, including a witch, though in fairness, she does invite this upon herself. In the opening, Fulci introduces her character conducting some vile black magic ritual involving the skeletal remains of a deceased child, and three voodoo dolls depicting the young boys we see taunting Giuseppe, the village idiot.

As the boys start turning up dead, her guilt seems obvious, until the murders continue whilst she’s held in police custody. Enter two outsiders, Andrea and Patrizia (played by Tomas Milian and Barbara Bouchet respectively), two very different people who come together to get to the bottom of the mystery. Despite the lukewarm reception that they receive (particularly Patrizia), the two of them soon discover the true identity of the killer, leading to a final, gripping confrontation atop a remote cliffside area.

Don’t Torture a Duckling was hugely daring and shocking at the time of its release, firstly for its use of graphic violence, but also for the themes that its narrative is built around, namely paedophilia and child murder, not to mention the dour light that it shines upon the catholic church. It is an overlooked masterpiece, one of the finest examples of the genre and a film that can easily stand up against the very best material that contemporaries Dario Argento and Mario Bava ever produced. If you only get to see one Fulci film, this should probably be it.

2. The Beyond

Released in 1981, The Beyond is the second instalment of Lucio Fulci’s unofficial “Gates of Hell Trilogy”, and another film that pays homage to Kubrick’s The Shining, at least to some extent. As with The New York Ripper, From Beyond ran afoul of the censors, particularly the BBFC who demanded that several cuts be made before it could be distributed, it remained in this form until it was eventually made available in its entirety in 2001, twenty years after its initial release in Fulci’s native Italy.

The plot is centred around the Seven Doors Hotel, a dilapidated establishment that New Yorker Liza Merrill inherits from some distant relative of hers. Naturally, she intends to renovate and reopen the business and so promptly sets off for the murky Louisiana backwater where it’s located. Unknown to her, the development work activates a mystical doorway beneath the structure which leads to all manner of incidents, starting with the death of a workman, Joe, and then his wife.

Liza is waned not to set foot inside room thirty-six, but she ignores this advice and does so anyway, though ultimately this leads to the discovery that the room was once host to an artist, and possible warlock, who was murdered by an angry lynch mob decades earlier.

Like The Psychic, we end up with a leading lady trying to prove her sanity when she starts seeing things that others don’t and yet, as the film steamrollers towards its superb ending, not very much really happens outside of an almost incoherent bloodbath.

The final segment steals the show, however, and ultimately drags the film back up out of the depths of cinematic hell where it might very well have been left to rot, and it is this that is surely seeing From Beyond now generating a much higher level of appreciation among film fans.

The critical reception that the film received upon its release was less than positive, and it’s quite understandable to be honest, it is for the most part little more than a hodgepodge of images collated together into a wholly surreal horror experience. But then, it was never Fulci’s desire to give film goers a standard modern horror film, it is as he described it an “absolute film”, one of images that should not be ruminated upon but rather taken at face value.

It would perhaps of benefitted from losing the dreadful soundtrack and some awful dubbing, conceivably it might have actually been better served as a silent film. Regardless, there are film fans who appreciate what Fulci was trying to achieve, and this is leading its improved standing, which is something that will likely only continue for the foreseeable future.

1. City of the Living Dead

Released in 1980, City of the Living Dead is arguably the most famous entry into the “Gates of Hell Trilogy” and operates as something of a test run for the film that was to follow it, From Beyond. Much like its successor, it feels like a montage of almost unrelated images have been cobbled together, though in this instance, Fulci manages to create and sustain a suspenseful atmosphere throughout, though this invariably comes at the expense of the surrealist experience he more successfully crafted with his following effort. Though for many, this is most likely a positive characteristic of the piece.

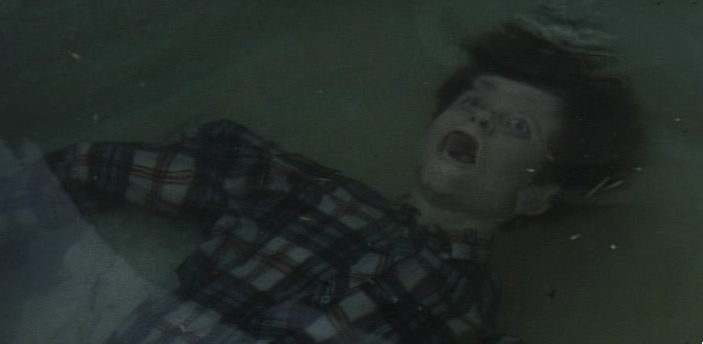

Opening with a séance wherein a young woman, Mary, has a series of terrifying visions involving the suicide of a priest, she falls to the floor, and, believed to be dead, she is rather quickly buried the following day.

A journalist, Peter, visits her grave and discovers that she is in fact alive and well, and, using a pickaxe, releases her from her burial chamber, thankfully her body was not subject to an autopsy before burial. They return to speak with the medium, Theresa, who held the séance and she warns them that Mary’s visions foretell the beginning of a dark prophecy that will see the dead return to claim the land of the living, the death of Father Thomas somehow opening a portal to Hell.

What follows are a wealth of set-pieces designed to turn the stomach of the most hardened horror fans as well as the character of Rose who spews up her own internal organs after a run-in with the dead priest who has now returned to haunt the living with a ghastly stare that can make one’s eyes bleed. Ultimately, this inevitably leads to a showdown in the family tomb of Father Thomas who finds his corporeal form disembowelled before bursting into flames, seeing the gates to Hell closed once again.

For many, City of the Living Dead will be little more than a formulaic Italian horror, there are bloody killings galore and the picture is populated with the stereotypical inclusion of ghouls and, you guessed it, zombies. As with the majority of his later efforts, there is a staunch reliance upon the grotesque, death scenes bathed in litres of blood rather than any semblance of coherent story exposition.

Of course, anyone else can make such films, but Fulci discovered his own way of doing things, and as such, his highly stylised movies cannot be consumed in the same fashion that we do other examples of the horror genre. Both the creator and his work were unique, and, as such, both will only continue to gain critical and commercial appreciation as wider audiences are introduced to this underappreciated film icon.