Forget the popcorn. These two words (and the article between them) pretty much sum up the list which you are about to read, considering that most of the entries are not the crowd pleasers and they demand your undivided attention.

Some films are less obscure than the others and half of them will make all the Nipponophiles out there very happy. Each year of the titular decade is represented by exactly one title.

1. Ra: Path of the Sun God (Lesley Keen, 1990) / UK

“All acts spring from the will of Ra. He sees all things. All thoughts are in the heart of Ra.”

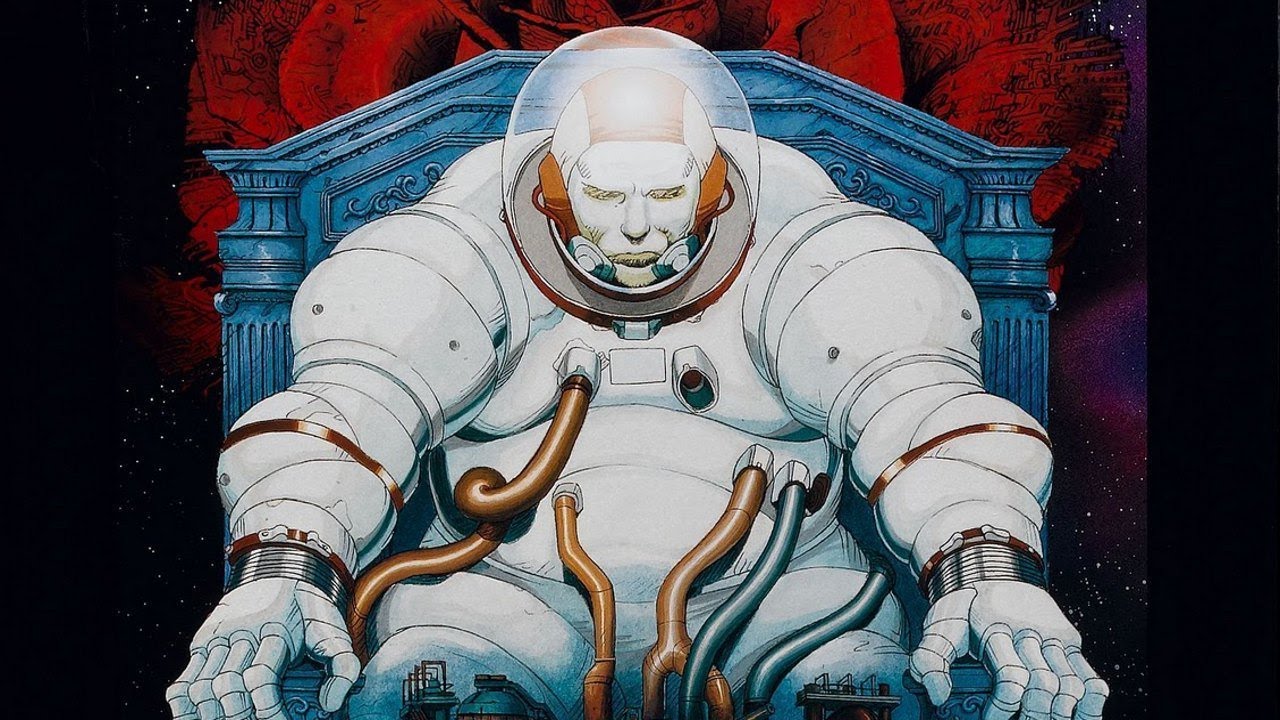

Good and evil Egyptian deities are brought to life as neon-lit specters in the first and, unfortunately, only feature-length offering from the British auteur Lesley Keen who made a stunning short based on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice in 1984. She does the writing, directing and animating, supported by a small crew (of ten), including a professional Egyptologist, Dr Geraldine Pinch, as a consultant.

Slightly reminiscent of certain works by Ishu Patel, her stunning imagery rests upon the fresco and papyrus paintings of ancient Egypt with all of their distinctive traits. However, she allows herself the freedom to modernize them, so she bathes both characters and objects in glowing light with the help of a specially designed rostrum camera operated by Mike Campbell.

This way, Keen achieves the looks of an oft-psychedelic and occasionally abstract phantasmagoria of hypnotic transitions and transformations occurring in the blink of an eye. Set against the black background and accompanied by the ethereal score and soothing narration of Tamara Kennedy (and later, Michael Mackenzie), her luminous line-work appears as embedded with mystic and magic qualities.

Unfairly forgotten today, this astonishing fantasy is also one of the most unique animated films – classic or otherwise. A passion project four years in the making, it is a reflection of its creator’s enviable skill and intelligence, expansive vision and fertile imagination, as well as a pure, dreamy audio-visual poem of spiritual, unearthly beauty.

2. Father, Santa Claus Has Died (Yevgeny Yufit, 1991) / Soviet Union

Loosely based on Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy’s gothic novella “The Family of Vourdalak (originally, La Famille du Vourdalak. Fragment inedit des Memoires d’un inconnu)”, Yevgeny Yufit’s esoteric, uncompromising feature debut is a great, yet not an easy way to get introduced to the art of necrorealism.

Written by the director’s frequent collaborator Vladimir Maslov, “Father, Santa Claus Has Died (Papa, umer Ded Moroz)” opens with a shot of a wire noose in a flooded underground tunnel and immediately establishes the suffocating atmosphere of death and decay. Exploring existential dread, it could be labeled as a grim, absurd, experimental drama/horror/mystery/pseudo-SF or a demented social satire with Kafkaesque overtones.

The film tells (or rather, obscures) the story of an unnamed biologist (Anatoliy Egorov) who is supposed to write a thesis on a shrew mouse, but ends up in his beastly cousins’ village. Once there, he becomes involved in a series of bizarre happenings involving his creepy family and a sinister bunch of elderly men in suits.

Yufit’s stark B&W cinematography perfectly captures the dreariness of the arcane proceedings and unsettling circumstances surrounding the disoriented protagonist. Even the most mundane activities are depicted as strange, not to mention utterly depressing, with as much as a pinch of pitch-black humor. The absence of music, languorous pace and long, frequently static takes intensify the dismal mood with the power to turn the most cheerful person into a suicidal wreck.

As things go from baffling bad to mind-boggling worse for our hero, the viewers are left scratching their heads and having their patience severely tested, despite the time frame of less than 80 minutes. And it is not only Santa Claus who is dead as a doornail here, but the Easter Bunny, Sandman and Tooth Fairy as well.

3. Franz Kafka (Piotr Dumała, 1992) / Poland

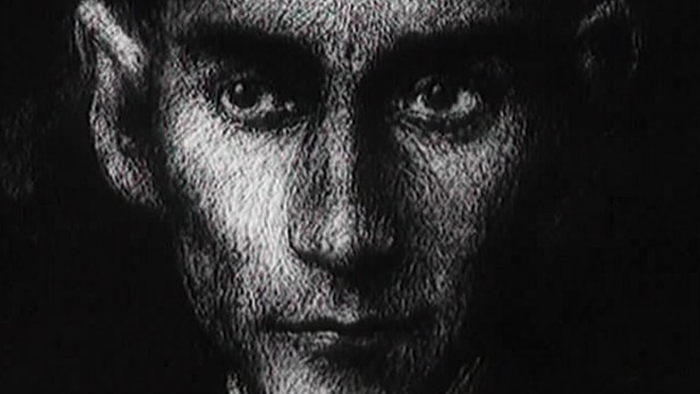

Franz Kafka is resurrected to a dreary life in Piotr Dumała’s award-winning, dialogue-free short film – a little, yet timeless masterpiece of “destructive”, plaster-etching technique of animation. Based on the prominent literate’s own diaries, it combines biopic elements with references to his opus and nightmarish sequences to a great effect.

Setting of with Kafka’s chiaroscuro portrait of fading glimmer in his eyes, it takes a sneak peek into his mind, while depicting Prague of the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a claustrophobic prison. Imbued with funereal stillness, absurd lyricism and surrealistic predicaments, it reflects some of the themes explored by Kafka himself, such as isolation, alienation and existential anxiety.

Complemented by the melancholic soundtrack, Dumała’s unapologetically murky, ghostly images – more black than white – move with elegance, building a brooding, contemplative atmosphere and generating an inscrutable, fragmented narrative of eccentricities and never-ending metamorphoses. When unidentified agents appear at K’s door, he transforms into a dog.

It is not hard to deduce this is not your average “cartoon” and is certainly not recommended for young children or the easily offended for that matter, given that it features a scene which embodies naughty, incestuous thoughts and a shot of Kafka lying in bed with his penis erected.

Best viewed in complete darkness, “Franz Kafka” ages like a fine wine and gets better with each subsequent rewatch.

4. Horror Story (Jaroslav Brabec, 1993) / Czechoslovakia

Inspired by the Czech artist and philosopher Josef Váchal’s novel of the same name, “Horror Story (Krvavý Román, literally translated as Bloody Novel)” marks Jaroslav Brabec’s feature debut and can be described as a less extravagant predecessor of Guy Maddin’s “The Forbidden Room”.

An affectionate homage to silent cinema and early talkies, it is a wild, whacky genre mash-up which will probably make you wandering what the hell it is about. Starring Ondrej Pavelka as the writer of the original work and two of his characters, it is a meta-fantasy of sorts, involving an elderly Catalan prince, finger-chopping revenge, doomed lovers, hunting accident, regenerating beauty, cannibalistic practices, drunken pirates, money forgery, sneaky Jesuit priest and much, much more.

Oddly paced, this pulp gothic horror turned cheesy romance turned slapstick comedy turned oversea adventure turned artsy rumination (!) gets progressively weirder and harder to follow, yet it remains fascinating until the last minutes. Multiple storylines collide, intertwine, end abruptly and turn in unexpected directions, so it would be an understatement to say that the story-within-story structure is broken.

The playful, mischievous direction is matched by the superb performances of the entire cast who excel in emulating the silent era stars’ mannerisms. Also praiseworthy are the eclectic score, strong makeup, swell costume design, Brabec’s delightful cinematography, various editing techniques and hand-painted, intentionally artificial sets, which all convey the sense of watching an ancient film.

Pavelka’s i.e. Váchal’s voice-over, the inappropriate sounds and anachronistic jokes simultaneously dispel the illusion and contribute to the well-intentioned mockery.

5. Rampo (Kazuyoshi Okuyama, 1994) / Japan

Based on Edogawa Rampo’s writings, Kazuyoshi Okuyama’s directorial debut “suggests an Alfred Hitchcock film that has been stripped of its pulpy Freudian psychologizing and elevated into a meditation on the artistic imagination”, in the words of Stephen Holden for The New York Times.

In its subtle interweaving of dreams, reality and fiction, “Rampo” appears as a peculiar neo-noir melodrama of solemn atmosphere, elaborate aesthetics and, in its second half, twisted eroticism and aristocratic decadence. It opens with B&W archive footage, but soon moves to a mystery section of a library, revealing Rampo’s main sources of inspiration – Edgar Allan Poe’s and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s books – in full color.

These pre-title sequences are succeeded by a highly stylized animated adaptation of a soon-to-be censored story about a man who hides in a treasure chest (nagamochi) during a hide-and-seek game and suffocates. A little bit later, an unpublished work eerily coincides with a newspaper article on a murder case and from that point on, fantasy and reality begin to merge.

Exquisitely played by Naoto Takenaka, Rampo walks the blurred line between the said extremes, obsessing over a suspicious widow, Shizuko (the wonderful Michiko Hada), who brings to life his alter-ego – the private detective Kogorō Akechi (Masahiro Motoki). The famous novelist known as “the Japanese Poe” is portrayed as a bemused introvert who retreats into a cocoon of ink and paper, only to emerge as a dandy, handsome, self-confident “butterfly”.

Externalizing his subject’s inner world via the expressive, painterly imagery and lush, orchestral score, Okuyama reflects on passion and artistic creativity, pays a loving homage to “Vertigo” and “Psycho” and ends the film on a surrealistically ambiguous note.