At its most fundamental essence, cinema is a representation of our lives. The grandiosity of an image on a movie screen can encourage us to laugh, move us to cry, or just stare in wonder as a foray of colors, shapes, and sounds culminate together to create…something new. When we watch a film, we choose to enter through a door of exploration, at the behest of its director, and we allow them to take us somewhere completely and totally unexplored.

When we relinquish such control, the men and women who create those films know it and they seize upon that opportunity. Opportunity to do what? Quentin Tarantino will tell you that it’s his job to entertain you through cathartic violence with a heavy dose of witty Chandler-esqe dialogue, pulp fiction, and a plethora of enough Spaghetti Western references to make even Sergio Leone laugh. Lars von Trier will bluntly assert that it’s his job merely to exploit you through the innate abuse of his characters, all for the betterment of a greater cinematic experience.

Documentarians like Morgan Spurlock (Super-Size Me), Joshua Oppenheimer (The Act of Killing), or even Michael Moore (Bowling for Columbine) will all tell you that cinema is about education, the experience of watching a film and learning something at the end of the day (usually they aim for some sort of appreciation towards a new perspective or learned opinion about a specific topic). At its most fundamental essence, cinema is a representation of our lives as well as our ability to learn and grow as human beings.

A social commentary is the manipulation of story all for the means of providing some sort of observation on issues within society itself. This is often carried out by the director, their hope to promote change by informing and educating the general masses about a specific problem that they deem important. In this sense, issues raised in social commentaries often appeal to the public’s sense of justice and hope for a conclusion that will bring about a shift in society to right the wrongs.

1. The Dirties (2013): dir. Matthew Johnson

The directorial debut of Matt Johnson (VICELAND’s Nirvana the Band Show), “The Dirties” is a beautiful ode to pop culture, wrapped intelligently around a meta-narrative of betrayal, heartbreak, and tragedy. The film centers around two high school outcasts Matt (Johnson himself) and Owen (Owen Williams) as they plan, shoot, and edit their project film titled “The Dirties” for their high school film course.

This film within the film revolves around Matt and Owen, two hard-boiled detectives (akin to that of a hybrid of Chinatown’s Jake Gittes, Humphrey Bogart, and Kill Bill’s Beatrice Kiddo) as they plan to hunt down the bullies that have done them wrong in the past.

Throughout the duration of the primary narrative, Matt and Owen are plagued by the torments of adolescence, bullies, and loneliness. The obvious losers, their immature antics alienate them from seemingly every high school click, but they don’t seem to mind because they have each other and movies. Owen, however, decides to make a turn and reject his outcast lifestyle, opting to learn the guitar and talk to the pretty girl, whereas Matt succumbs deeper and deeper into his film.

Convincing himself that it is “all a part of the movie” or “the project for school,” Matt takes alarmingly complex and threatening steps into securing his revenge against all those who have wronged him once and for all. He studies blueprints of his school, manages to secure a firearm, repeatedly tells those that wrong him that he is going to kill them, and at one point, when it is evident that Matt has almost completely lost his mind, he looks directly into the camera and plainly declares “I can’t believe that it is this easy.” The climax is shocking, haunting, and leaves the viewer begging for just one minute more.

To say that this film is a critique of gun rights in a world where there is seemingly a new mass shooting almost every week would be grossly underestimating the talent and layering of Matt Johnson’s story. It is a tragedy of misunderstanding those around us and the red flags after the fact.

Matt was a clearly troubled individual, not because he had been a lunatic or an evil individual, but because he had been pushed too far and simply had had enough. He was a kid who escaped through his film project, and used it as a means to detach himself from reality.

Yes, gun rights is an element of the story, and the debate can be had accordingly to what was portrayed in this film, but the real commentary is a reflection on how our actions are sometimes the catalyst for much greater (and sometimes horrific) events.

2. The Lobster (2016): dir. Yorgos Lanthimo

With each film Yorgos Lanthimo casts into the mainstream, the more intriguing he becomes. Both his critically acclaimed Dogtooth and Alps each had something to say about the roles of language, character manipulation, and the nature of truth within the present realm of society, but not as prolific as it was in “The Lobster”.

In this exploration of human interaction and interpersonal relationship, David (Collin Farrell) is a man who has lost his wife to another man. In retaliation, he allows himself to be taken to a clinic on the outskirts of a dystopian society. It is here that they explain to him that single people have 45 days to find a partner or they will be transformed into an animal. As the title suggests, David chooses to be turned into a lobster if he cannot find love. In the clinic, masturbation is prohibited, but sexual stimulation by the hotel maid is mandatory.

Additionally, patients attend dances and watch propaganda telling of the advantages of relationships. It is a cold, sterile environment where relationships are acutely dissected and put under a microscope. Through numerous cameos (most notably John C. Reilly and Skyfall’s Anthony Moriarty) paired along with Farrell’s character, the dichotomies of relationships and what truly constitute human connections are reevaluated.

For example, John (Moriarty) (a fellow patient) feigns a human connection with a young women out of sheer fear of being turned into an animal. He successfully manages to fool every one of his newfound love as genuine and is able to continue in his treatment. It is ironic that when David finally finds his love much later in the film, she is considered an outsider to this dystopian society and must even still conform to her ideals, even if it ultimately means sacrificing everything that he holds dear to him.

This film is a truly epic examination of one of the greatest mysteries of the human condition: our desire for love. In a world of domination at the hands of social media, extremely superficial beauty standards, and numerous pressures presented by life itself (work, money, and whatever else you can think of that worries you), Lanthimo creates an incredibly oblique, yet personal incursion into the human psyche.

The film seeks to explore what really ends up constituting the relationships in our lives, ultimately begging the question of what is creating them in the first place.

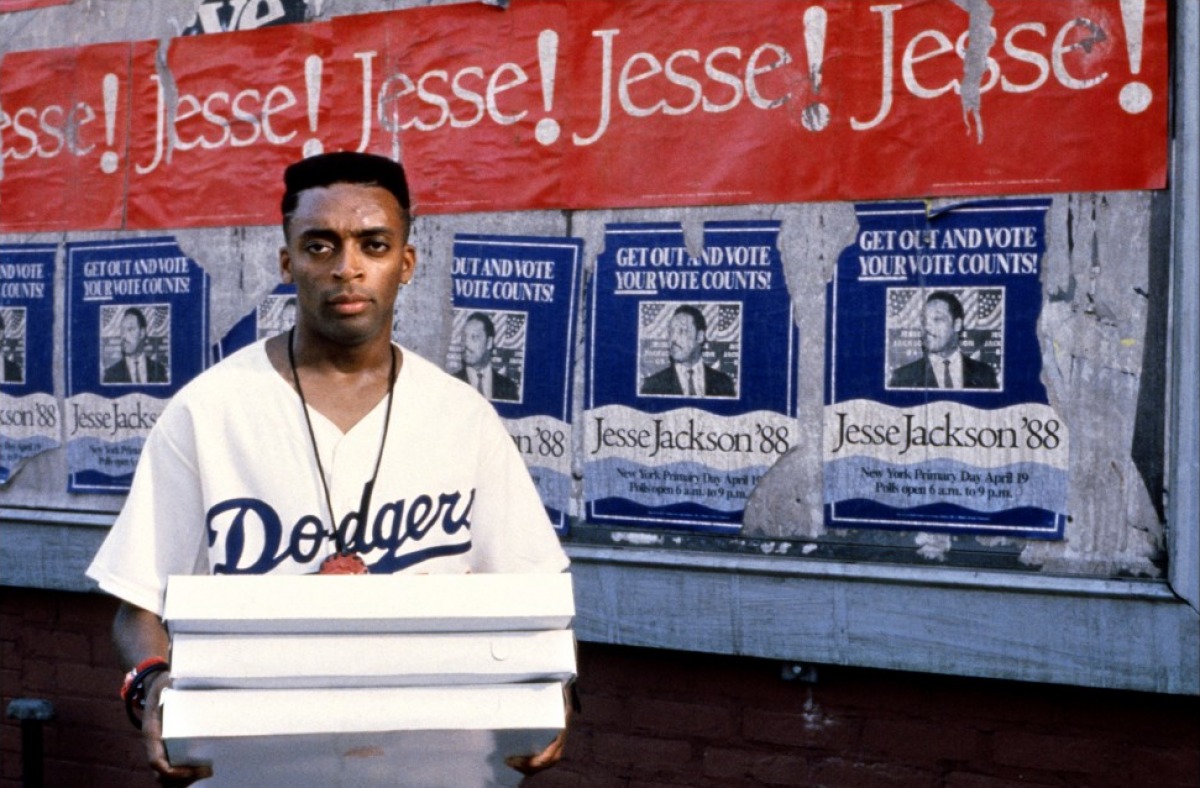

3. Do the Right Thing (1989): dir. Spike Lee

If there is one film on this list, however unfortunate, that seems to transcend time within the context of a post-Civil Rights United States, it is indeed Spike Lee’s 1989 “Do the Right Thing.” Its original inception birthed from the erosion of race relations within United States in the late 20th Century, this film seeks to address the topics of not only racism itself, but also perceptions on the injustices of prejudice.

In the context of the story, the relationships of Blacks, Whites, Italians, and Koreans (most are common citizens, but some are police authorities) on a block in a Brooklyn neighborhood are put to the penultimate test on one of the hottest days of the summer.

The story primarily centers around Mookie (Spike Lee), a mid-20 something average-Joe. He has a child, a girlfriend, and tries to keep his nose clean in the rough streets. In his free time, he works as a pizza delivery boy for Sal (Danny Aiello). Sal, the minority Italian in the neighborhood, runs a thriving pizza shop, which has been deeply integrated into the neighborhood (having been feeding the kids of neighborhood for years). His two sons help him run the shop, but hold prejudiced reservations about those they serve.

Around this central storyline of trials and tribulation, other colorful characters roam these streets, each more complex and interesting than the last. Most notably there is the menacing, radio touting Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn), loudmouth Buggin’ Out (Breaking Bad’s own Giancarlo Esposito), and the drunkard (yet enlightened) Da Mayor (Ossie Davis).

What is absolutely brilliant about Spike Lee’s direction and story is that it manages to intricately balance the interconnected storylines and perspectives of every single person the camera choses to follow, begging the question of who is right in each situation (and managing to keep that answer intentionally neutral).

This morally impartial position is kept and maintained throughout the film, stoking the fires of intellectual curiosity and perspective, even to the film’s tragic climax. That is what is so utterly perfect about this film, because even after the credits have begun to roll, you still think about it. There is a much deeper meaning veiled behind this conventional story of racism and heartbreak.

In contemporary American society, this film is more important now than it ever was. The fact that anyone who is at least moderately aware of the spiraling race relations within the United States can watch this almost 30 year old film and convincingly believe it could have been made been made in 2017. That is something to think about. In an era of the 2015 Baltimore Riots, the rise of the Black Lives Matter Movement, and the gradual questioning of systemic prejudices in US policing institutions, “Do the Right Thing” still asks so many questions that have yet to be answered.

4. I’m Still Here (2010): dir. Casey Affleck

Joaquin Phoenix is most certainly a powerhouse presence on the big screen, but “I’m Still Here” solidifies him as one of the greats. In this 2010 film on media manipulation and the psychology of fame and character, Director Casey Affleck follows Phoenix as he attempts to carry out a plan to retire from acting and concentrate on a new career as a hip-hop musician. Ridiculous as this may sound, we all remember that time when we thought that the actor had finally lost it, and if you don’t remember when exactly that was, it was during the filming of this comedy-drama.

The film not only centers on pontification after pontification delivered by Phoenix on the idea of the superstar personality and the media, but also on instances where he samples his new music to massive crowds, attempts to hit the circuit, and surprises Letterman with a stupefied, bizarre, and tranquilized performance (sporting the trademark rugged beard and sunglasses).

On the surface level, the film portrays the mid-life crisis of a highly talented actor, emblazoned by years of reputation and success, starting to slowly lose his grip with everything else around him. Abstractly, as we know now, it was all a lie. A farce constructed by Phoenix and Affleck themselves to illustrate the power of celebrity and its subsequent manipulation at their hands. The film itself is a fascination examination of the role of popularity and controversy, in just how easy something false can shape something so major.

5. Four Lions (2010): dir. Chris Morris

Four Lions is more of a black comedy than it is that of a social commentary, but sometimes the act of laughter and the art of humor can often bring to light many issues which we never previously saw before. Four Lions delves into the subject of terrorism, more specifically radical Islamic terrorism. Yes, that phrase alone is a political quagmire in and of itself, but before anything gets too partisan, the film most definitely has something to say about it, and that is what is important here.

In this film, a bumbling group of young British Muslims become radicalized, aspiring to become suicide bombers and wage jihad. This posse is led by Omar (Riz Ahmed), and underneath his command is his cousin Waj (Kayvan Novak), Barry (Nigel Lindsay), and Faisal (Adeel Akhtar).

Throughout the film, senses of duty and inspiration are questioned and tested, if in the most absurdly comical means possible. They attempt to attach C4 to crows as a means to wage terror. They cook the sim-cards of their phones in order to maintain a low profile. They even so much as travel to Pakistan and train with Al-Qaeda affiliates and, in the process, manage to completely fail. In a pre-Boston Bombing context, the film decides that these characters will ultimately target a British fun-run marathon, where they must dress in ridiculous and silly costumes in order to better conceal the explosives under their disguises.

As the film nears its third act and the actual action of jihad must be carried out, the story, as is typical in most black comedies, takes a much more menacing and dark turn. We aren’t laughing at these idiotic fools anymore, but rather, we become afraid of them as their actions steadily become more real. We watch in horror as these men become more desperate to carry out their actions, some of them even regretting what they plan to carry out.

At the film’s conclusion, we are merely left sitting there to think “why did they act in this way?” At first, we laughed at them, but soon enough, we were crying with them. Four Lions is a perfect example of a film asking us to sympathize with those that we do not understand and, in a world plagued by fear and terror, an attempt at consideration for the other side (even if it is for our safety) is extremely relevant.