The 1990’s were Scorsese’s most productive period, a decade that included some of his most recognized work (Goodfellas, Casino) as well as personal projects (Age of Innocence and Kundun) and everything in between (Cape Fear, Bringing out the Dead).

The 90’s were not just the period where the director worked most consistently it was the decade where he put his lifelong passion for the art form on full display with A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies.

Scorsese’s encyclopedic knowledge was never a secret but with his 1995 documentary he had reframed the history of film by reflecting what made and impact on him, his nearly four-hour discussion tackles many of the usual suspects when it comes to film history, Citizen Kane is featured prominently, but movies like Cat People and Leave her to Heaven are every bit as important in the context.

What was less well known than A Personal Journey was an extensive write up for Film Comment in 1998 focusing on his guilty pleasures; a write up that could serve as a companion piece to the film.

The article is a testament not only to how expansive Scorsese’s obsession with film goes but how films even the ones that are flawed or just bad can still have a dramatic impact on the kinds of artists we become. Here are some of the highlights from the one hundred films listed.

10. Frankenstein Created Woman (Terence Fisher, 1967)

Scorsese has admired The Hammer Horror films since their heyday. You can catch a younger bearded version of the director in the documentary ‘Hammer the Studio That Dripped Blood’ discussing how the productions bold style impacted him as a future filmmaker.

For his list of guilty pleasures Scorsese singled out this oddball entry. The Frankenstein films which followed Peter Cushing’s mad doctor might not have been the most consistent series, but watching the doctor develop over several films is rewarding in places. This film has Frankenstein taking a backseat to many minor characters all of whom he damns almost by accident.

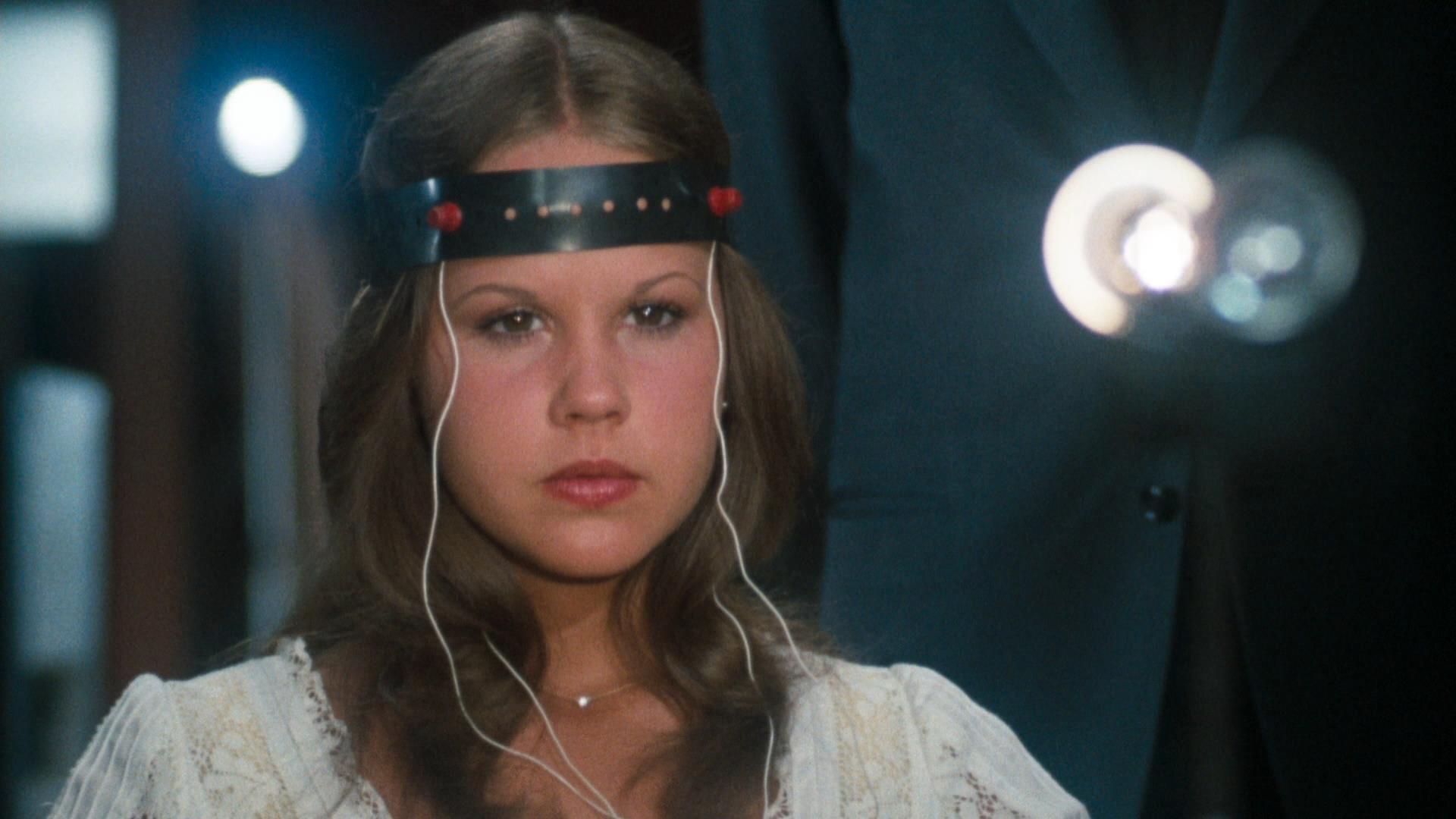

The plot involves the doctor conducting experiments in isolating the soul for the purposes of resurrecting the dead, as ludicrous as this sounds director Terence Fisher treats the subject matter with sincerity. The moments that the soul becomes tangible showcase the colorful vibrancy the studio was known for “The implied metaphysic is close to something sublime”, as the director puts it.

The script is not perfect but it is especially sadistic, saving the worst fate for the two most innocent characters in the experiment. The final third becomes a revenge story with some pulpy violent moments worthy of an EC horror comic. Frankenstein Created Woman isn’t the only Hammer film to make an appearance in the article, the even weirder Vampire Circus and Captain Kronos Vampire Hunter both get brief shout outs.

9. Twelve O’clock High (Henry King, 1949)

Henry King is a largely forgotten craftsman who gets a brief mention in A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese through American Movies. Twelve O’clock High is a war film about the air force that is light on combat and heavy on process.

At the center is tough as nails Gregory Peck, portraying real-life Colonel Frank Armstrong in a script inspired by the accounts of bombers and bombardiers who knew him. The film is a long series of exchanges featuring Peck reshaping his crew for future missions without any illusions of the outcomes, a sense of dread hangs over even the most procedural scenes.

Twelve O’ clock High doesn’t have the beats typical of most war films, in fact many scenes feel outright anti climatic, but the meticulous structure really does pay off as it ends up feeling more like a well-oiled machine where lives are just statistics and no one has any knowledge of the psychological implications of war.

The film was praised for its detail and accuracy upon its release by airmen and is allegedly still shown at leadership seminars today. While the whole thing is decidedly pro war, the climax is anything but triumphant. The stark depiction of combat shock is a sobering contrast to everything that came before.

In one of the funnier observations in the article Scorsese talks about Peck playing up a familiar persona but being taken back by the movie’s sudden humanity. “Gregory Peck is Gregory Peck, when he’s in a film you accept it for what it is, it’s a given, like a theorem in geometry, okay, Gregory Peck…but then comes the moment when he has to get into the bomber, and the machismo breaks down. He can’t get in the plane. And I love it.”

8. Road to Zanzibar (Victor Schertzinger, 1941)

Bob Hope and Bing Crosby may not be the most well remembered onscreen comic team but this outing is worth watching. There is looseness and surrealism to these two comedic personas being dropped into any number of Hollywood back drops with minimal explanation from the script.

In short, the heroes are con artist circus performers swindled into the jungle by their frequent costar Dorothy Lamour. It’s a plotline you might see in a dozen comedies from the era but Hope and Crosby’s rapid fire banter sets it apart and it keeps up whether the pair are wrestling gorillas, running from rear projections, singing songs or poking fun at the fact that they are in a film.

What does this have to do with Scorsese? He was actually fascinated by Bing Crosby’s onscreen persona as a guy who was sweet and charming on the surface while constantly cheating people, “He’s charming, he sings all the time — and meanwhile, he’s swindling everybody.

In the Road pictures, he takes advantage of Bob Hope from beginning to end — and still winds up with the girl” The running joke of Bing Crosby playing a guy repeatedly throwing his pal under the bus was the kind of relationship Scorsese would cite as an influence on the relationship between Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro) and Charlie (Harvey Keitel) in Mean Streets.

7. Al Capone (Richard Wilson, 1959)

Whenever Scorsese talks about genre pictures it often is a treasure trove for little seen gangster films like The Phenix City Story or this underseen take on the legendary gangster.

Directed by one of Orson Welles earliest collaborators from his Mercury Theater days, Al Capone admittedly feels like cliff notes of Capone’s life but for most of the runtime the simplicity of the story gives each scene a vignette feeling. Key players in Capone’s story, Bugs Moran, Big Jim Colosimo and Dean O’Bannon are each introduced with their own voiceover narration and the build-ups for each gangland death feels like its own short film.

Rod Steiger is an actor with a divisive reputation to say the least but here he is the right man for the job, mixing Capone’s charm and sleaze in many of the same moments and staging several flown blown meltdowns the actor would become known for.

The entire movie is remarkably unromantic depicting Capone as the source of corruption for everyone around him, especially during the (fictional) sub plot involving Al seducing the wife of a man he killed. There’s some overused newsreel voiceover but that’s a minor complaint. Scorsese would tackle a few of the events depicted in the film when he directed the pilot for Boardwalk Empire.

6. I Walk Alone (Byron Haskin, 1949)

Speaking of little seen gangster movies. Scorsese has included I Walk Alone in many of his reflections on the genre. Scorsese has a knack for finding signs of social upheaval in B-movies that never had much of an audience. This gangster /film- noir hybrid stars Burt Lancaster fresh out of prison and looking for a piece of the action from former partner in crime, Kirk Douglas.

The movie is about the shift in the world of crime after the great depression. Lancaster’s street guy finds himself out of place in a world of corrupt businessmen and is constantly one upped by Douglas who can buy off everyone around him and exert a control over every detail of his empire. On top of that I Walk Along has an unexpected visual flair, Lancaster points to a map that dissolves into a road and ends up being a flashback of the night he went to jail.

The new kind of gangsters in I Walk Alone is precursors to movies like Point Blank and The Godfather. Paramount produced this along with a string of other noirs like Sorry Wrong Number, fitting that Paramount’s glossy style was often contrast with Warner Brothers harder edged gangster pictures only few years earlier but here the studio’s signature gloss would become the new standard for cinematic crime.