Movies are made from other movies. There’s no way around it. To profess complete originality is equal to professing divinity; you’re either God or a charlatan, and there’s only one position available—if this can even be granted. Most directors know this; if they don’t they’re not helping the stereotype. Yes, art is a complex thing, but it’s only as complex as your favorite artists. The greatest directors have borrowed, wittingly or unwittingly, covertly or clearly, benevolently or malevolently, from their predecessors. This list will show ten scenes of such happenstance.

Some scene-peats are admitted homages, while others are too similar to be mere coincidence, but we’re not attributing fraud to the directors who have taken stylistic and thematic traits from the movies they love. It’s as simple as being inspired—and imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.

Warning: Spoilers

10. The Blair Witch Project Ending (Don’t Look Now)

Few scenes evoke such a helpless, visceral fear as that of the Blair Witch Project finale. The lack of resolution is the most unnerving part of what is a comparably tame horror movie climax. All we see, after the hour and a half of snotty buildup, is Heather stumbling upon Michael in an abandoned house. He is facing a wall in the corner of the basement.

What he’s doing against the wall, we’re not sure. Who put him against the wall, we’re also not sure. What is going to happen to him, and her, after this misfortune is also not revealed—she drops the camera and screams, then the film ends. Like most good tension-building horror films, it’s what’s not shown that is most effective, but Blair Witch takes this mandate to another level.

Never do we see the titular witch, and the circumstance surrounding the main characters’ disappearance is never made clear. Instead, The Blair Witch Project offers the perfect sliver of horrifying intrigue, and the viewer is left, after hugging his or her blanket, with the daunting task of filling the story’s gaps—and a shaken imagination will only think the worst. Thanks to this, the back-turned, wall-facing anti-reveal is a nightmare mainstay.

Consider a highly regarded but lesser seen film called Don’t Look Now. Starring Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie, and centered on a domestic disaster with supernatural consequences, Don’t Look Now is often placed in horror’s upper echelon, and, since gaining cult status, has doubtlessly imprinted its cerebral effects on multitude movie buffs—with the probable inclusion of one or both of The Blair Witch Project’s directors. Don’t Look Now’s ending resembles Blair Witch’s in many ways, and may be the source of the wall-facing trope.

After chasing what he believes to be his dead daughter—or the projected memory of said daughter—Donald Sutherland’s character corners the cloaked figure and urges it to reveal itself. The figure, back-turned and staring at the wall, evades his temptation for just as long as the tension becomes unbearable.

Finally, it turns around, revealing a hideous and otherworldly dwarf, who promptly kills him. The stylistic similarities between the two endings are unmistakable, with the only thematic difference being the monster’s reveal. If Don’t Look Now is not Blair Witch’s natural inspiration, it’s definitely its natural predecessor.

9. The Dark Knight Nightclub Scene (Collateral)

Michael Mann seems, at first thought, an unlikely inspiration for Christopher Nolan films. Don’t get us wrong, Michael Mann is a great director, but not a logical antecedent for the speculative-minded Nolan. However, thanks to exhaustive research, hundreds of similarities have been discovered between Nolan and Mann films—similarities that go beyond single scenes.

We’ll focus on one instance in particular to elucidate this point: The Nightclub Scene in The Dark Knight. In which Batman, deigning to apprehend a crime boss and joker ally, fights his way through a nightclub. The lighting, camerawork, and choreography are all similar to the respective nightclub scene in Collateral, where Tom Cruise’s hitman character fights his way through myriad adversaries to dispatch a target.

Other Dark Knight scenes, like Batman and Joker’s sit-down, are reminiscent of stylistic and narrative quirks in Mann movies, especially Heat and The Insider, and this extends throughout much of the Batman series. Even Nolan himself has admitted the influence.

8. Dog Soldiers Closing Shot (The Searchers)

Dog Soldiers is a cult hit which deserved more than the paltry sum it grossed. The inaugural entry from auteur Neil Marshall, who followed with The Descent and found his way into TV, directing seminal episodes of Game of Thrones and Westworld, Dog Soldiers made its mark as a brilliantly written and acted horror/thriller.

Set in Scotland and concerning six soldiers on a mission in the remote highlands, the film turns from tense character drama to all-out carnage without time to blink. But the transition is not forced; it is precisely causal. After a night-long battle which leaves all dead except for one, the last man stands in the doorway and looks upon the destruction as the sun rises. Then the credits roll.

The film borrows this serene doorway moment from one of Western’s greatest installations, The Searchers. In it, John Wayne stands in the doorway in the film’s final seconds, watching the family reunite, and meditating on the two hour epic that transpired before our eyes. The scene is practically identical to the one in Dog Soldiers, and leaves little question about conceptual connection.

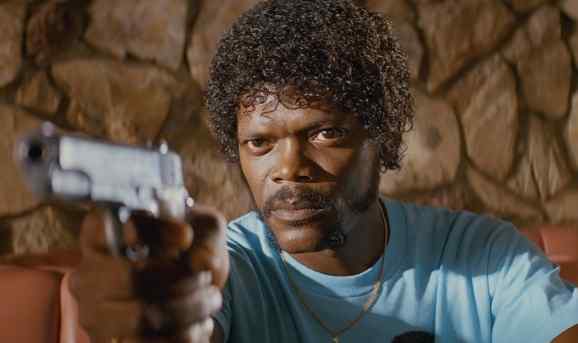

7. Pulp Fiction Ezekiel Speech (The Bodyguard)

Pulp Fiction is a collage of entertaining vignettes. Throw a dart at the screen and you’ll hit something spectacular. One of these often-mentioned vignettes is the “Path of Righteousness” speech. Ezekiel 25:17 is the verse from which Jules Winfield professes to recite in this memorable scene, though, as I’m sure you might have heard, this is false. But the monologue does indeed have an independent source; however it’s far from what you’d expect.

Tarantino, always the eclectic film viewer—aided by his work in video rental stores—took Sam Jackson’s righteous words nearly line-for-line from an unknown Japanese karate film called The Bodyguard. The speech comes from the opening scene, in which the future-Pulp Fiction text appears on screen and is read as a prologue to the film. The Bodyguard originates the Ezekiel misattribution, and, thanks to Quentin, new generations have inherited this mistake.

Tarantino, the greatest sampler of superior art since Puff Daddy, paid homages to several other movies in Pulp Fiction, including Psycho; when Bruce Willis’s character stops at a traffic light and finds Marcellus Wallace crossing the street the same way Janet Leigh finds her boss doing the same. Another is the Vincent and Mia twisting dance sequence, which mirrors the dance scene in Fellini’s famous 8 ½.

6. Back to the Future Climax (Safety Last!)

Time is the obvious theme of Back to the Future, so it makes sense for the climactic scene to make use of a clock tower for symbolic purposes. We all know how it goes: Doc Brown rigs a power line from the clock tower to conduct the storm’s energy towards Marty’s car to spark the reaction to take him back to the future. But it doesn’t go completely smoothly of course—there has to be hiccups, like Doc slipping off the tower and hanging from the clock forty feet off the ground. There’s subtext at hand here, but it’s not just symbolism. It’s homage.

Just as Christopher Lloyd does in Back to the Future, Harold Lloyd did in the legendary silent movie Safety Last! The comic actor used Safety Last! as a foil for his surreal sight gags, one of which is a stomach-weakening sequence from atop a clock tower. Lloyd narrowly avoids plummeting to his death by virtue of luck and coordination, but not before working the audience into a sweat.

Robert Zemeckis was so enthralled by that scene he passed the torch to another—unrelated—Lloyd, who hung from the clock in the same fashion. Back to the Future is far from the only film to parrot Harold Lloyd’s clock gag. Two notables being the 1983 Jackie Chan film Project A and the 2011 Scorsese film Hugo.