6. Braveheart

History as legend, not fact (think Frank Miller’s ‘300’) where the side that wins, or needs the propaganda, controls the story.

Very clearly, at the start of the film, Robert the Bruce tells us that he is about to recount the story of William Wallace. We don’t know it yet, but Robert the Bruce turns out to be a turncoat who comes back to the right side by story’s end. He is a reformed Judas, if you will. Should we trust him?

Why it is important to have the actor who plays Robert the Bruce start the narrative speaks a lot to the film’s historical inaccuracies. Many complaints were levied at the film, which eventually won Best Picture surprising many people. The chief complaint was that historical facts were bent or outright broken in the narrative, and several key plot points couldn’t have happened, and the film was guilty of homophobia.

The film does in fact do all of these things, but perhaps there is an overarching reason why. The losers are telling the story.

As is well established in the film, in history, and even recent referendums, Scotland cannot organize against the British for long enough to become independent. It is this infighting that keeps the clans from uniting until the end of the film (although history would have us know it didn’t last long).

But if you were going to tell the story of a great warrior, or at least a great strategist, would you include all the sad political details? No, you would accuse your enemies of being gay dandies who couldn’t get a woman pregnant. The entirety of Braveheart is a legend’s brag, or a fanciful story told around a campfire to preserve national identity in the face of an invading force.

Sterling bridge lost the bridge in the movie because the original strategy was somewhat of a cheat of warfare rules of the time. Can’t show that now can we?

7. Interstellar

The “happy ending” is all the dreams of a dying man.

One of the only maligned Christopher Nolan films was greeted with anticipation, to slowly fade away as a joke about space ghosts and Matthew McConaughey’s pronunciation of “Murph.”

Near the end of the film, after a few questionable monologues from Anne Hathaway and Matt Damon, Cooper heads into a black hole (beautifully rendered by the calculations of noted astrophysicist Kip Thorne) along with a robot that will somehow relay information to earth, which will allow man’s survival after we’ve turned the planet into a new dustbowl. A lot of people were confused or let down by the happy ending.

But just as with Memento, Nolan’s concerns aren’t as cold or clinical as he would lead you to believe. The film references on many occasions, a poem by Dylan Thomas, Do Not Go Gentle into that Good Night. At one point, the oldest person in the film repeats it over and over. What sounds like an admonition to humans not giving up in the face of annihilation is actually a eulogy.

The poem itself includes many references to celestial objects: sun, dark, lightning, waves (like the water planet), and meteors. The poem is a treatise of the inevitability of death, and our responsibility to not take it lightly, and therefore, not take life lightly either. Rage against the dying of the light. The poem in the film is a final gasp and release symbolized by Michael Cain.

Cooper enters the final moments of death in the black hole, he almost died on the ice planet where the idea was first suggested that people see their loved ones before dying, and in an effort to save his family, and humanity, he does in fact rage against the light. The entire film is a momentary vision before his death. He is truly a ghost in the bookshelves, but perhaps not a literal one.

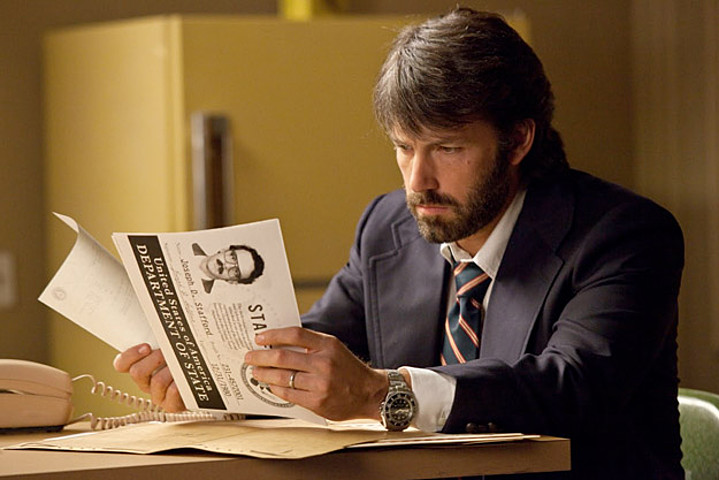

8. Argo

A critique of Hollywood and entertainment as being able to re-write history.

Ben Affleck’s Oscar winner took great liberties with the actual story of the rescue of embassy workers during the Iran Hostage crisis. Another example of American filmmakers taking a little known, or little covered part of a story that most people in America might have forgotten or was overshadowed by the larger news story, and spinning a tale where we are the heroes.

Canada rightfully had qualms with the blockbuster film as they were more involved than the film would suggest. And of course there was no airplane chase at the end of the story. But little talked about are the elements that make this whole film a commentary on such films as it depicts.

The entire ruse used, in the film, and partially in real life, is that of a producer making a film in Iran and folding the embassy workers that escaped into the production team and flying off with them safely. What this specifically belies is the motive of the Argo filmmakers’ commentary on Hollywood’s ability to shape a story for dramatic purposes, but also make propaganda whether it be for the war on terror, or American ingenuity in the face of adversity abroad.

The entire film is an exercise in the subterfuge at the heart of the original narrative, only this time, we the viewers are fooled because we failed to pay attention to history. Much like many of the entries on this list the power rests in who is telling the tale. Modern studios may have liberal agendas in theory, but they are still part of a capitalistic industry in America that values the dollar more than ideals. Audiences want their money’s worth.

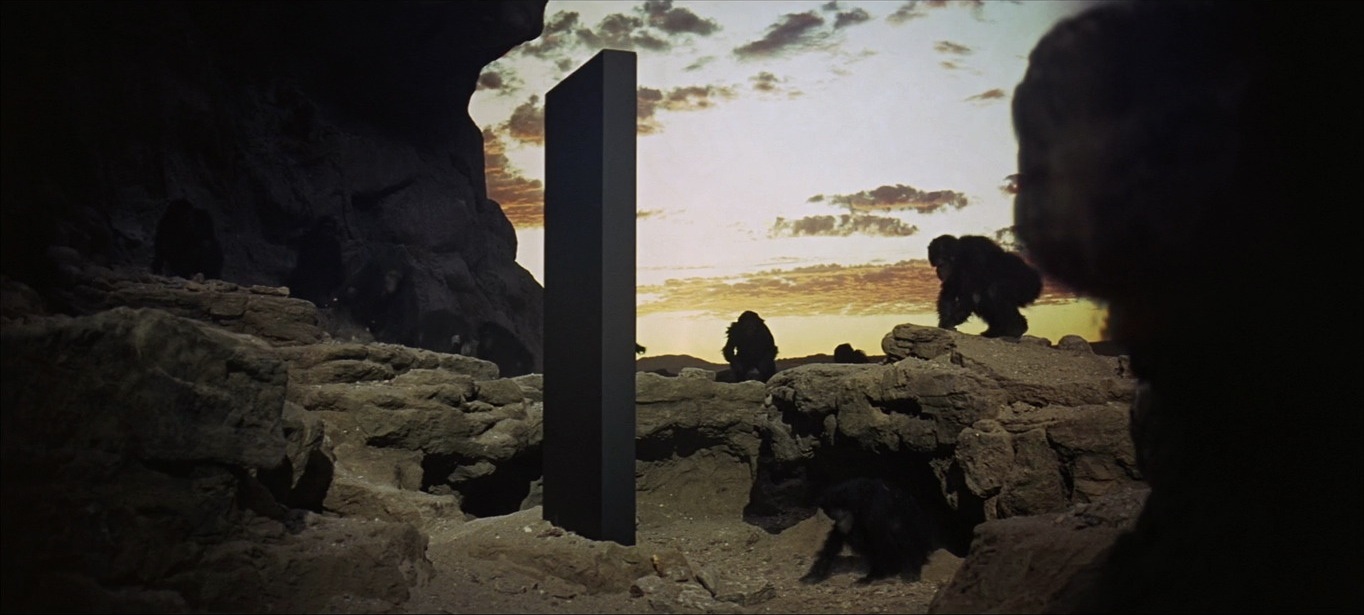

9. Bonus entry – 2001 is all about Nietzsche’s Overman.

There are three parts or stages to Nietzsche’s theory of the Ubermensch that man must transition through to become above morals and above human. In his text of Thus Spoke Zarathustra he outlines these steps to higher order being, much like a Biblical voice in the desert calling out a gospel, or perhaps a Greek orator imparting wisdom to his pupils.

He states that man must first be a camel, a workhorse that toils and breaks his back in labors. Next he must be the lion, full of intellect and pride as he rules the desert, and lastly the infant fully transitioned to the higher order Ubermensch.

Interestingly, 2001: A Space Odyssey also has three movements. It also begins with Strauss’s tone poem Also sprach Zarathustra at the dawn of man. Human kind lives through the age of the camel as proto-humans begin to use tools, jump cut thousands of years, and we are still only camels in space. Once the second monolith is found, man has become a lion and journeys to Mars with a higher purpose, taking what amounts to our own camel with us in HAL.

Before the stargate sequence HAL is shut down for its own attempt to overcome his camel-ness, and transition to a lion. Dave is a lion that cannot allow that. Finally he enters the stargate and assumes an entirely new form of being and consciousness as the star child, watching earth ready to outgrow it once and for all.

10. Bonus entry #2 – The Shawshank Redemption – Andy Dufresne did it.

As beloved a film as The Shawshank Redemption is, it would be tricky to interpret this film in any other way than the popular appraisal of its narrative. Only one things sticks out from this: Andy Dufresne is never exonerated for the murder of two people. From a narrative standpoint we want to believe that he and Red are heroes by movie’s end, but Andy escapes without completing his sentence, and Red is finally paroled after accepting himself as a criminal.

More importantly we the audience are complicit in jailhouse rumors and crooks trying to get a little extra special treatment while in prison. We believe the ramblings of a thief who recounts a tale of an old cellmate that has implications for Andy, but is never explicitly dealt with in the narrative.

For all we know this could have been a lie, or at best, a misheard story from Tommy Williams. We never meet the guy who claims he did the murders. The warden kills Tommy without much thought because he is a bad man and has something to hide, but that still does not forgive Andy.

So in the end of the film we have successfully cheered on a double murderer to escape prison and move to a country without extradition. What happens if he marries again? Red always claimed that everyone in Shawshank did not commit their crimes except him, but he meant it as a joke. They were all guilty.

Author Bio: Andrew Bockhold is a writer from Ohio. You can check out his writing here, and here. You can also find him working at a small university during the day, and feeding his addiction for movies at night.