5. The Red Shoes (1948)

Perhaps the crowning cinematic achievement from The Archers (the collective nom de plume of the writing/directing/producing team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger), The Red Shoes is a cinematic dramatic classic in every sense of the word.

Ostensibly the tale of an aspiring ballerina named Nicky Page (Moira Shearer), who’s torn between her dedication to dance and her desire to love a young, bright-eyed composer named Julian Craster (Marius Goring). Nicky’s emotional stress, eloquently communicated through, amongst other strategies and techniques, the shockingly creative use of Technicolor has ensured that The Red Shoes is one for the ages.

A classic retelling of the Hans Christian Andersen fairytale about a ballerina donning a pair of red slippers that will not allow her to stop dancing, this is also the film that convinced the near peerless cinematic stylist Brian De Palma to be a filmmaker, as well as being “the movie that plays in my heart” for Martin Scorsese.

The Red Shoes adds new dimensions to the often delicate interplay of light and color, making a visual landscape that was previously unseen. Packed with creative camera compositions, beautiful dancing choreography, and a seemingly endless parade of gorgeous and lush production, comparable only to the Busby Berkeley monochrome of the 1930s, amounting to the most vibrant and colorful fantasy musical ever made.

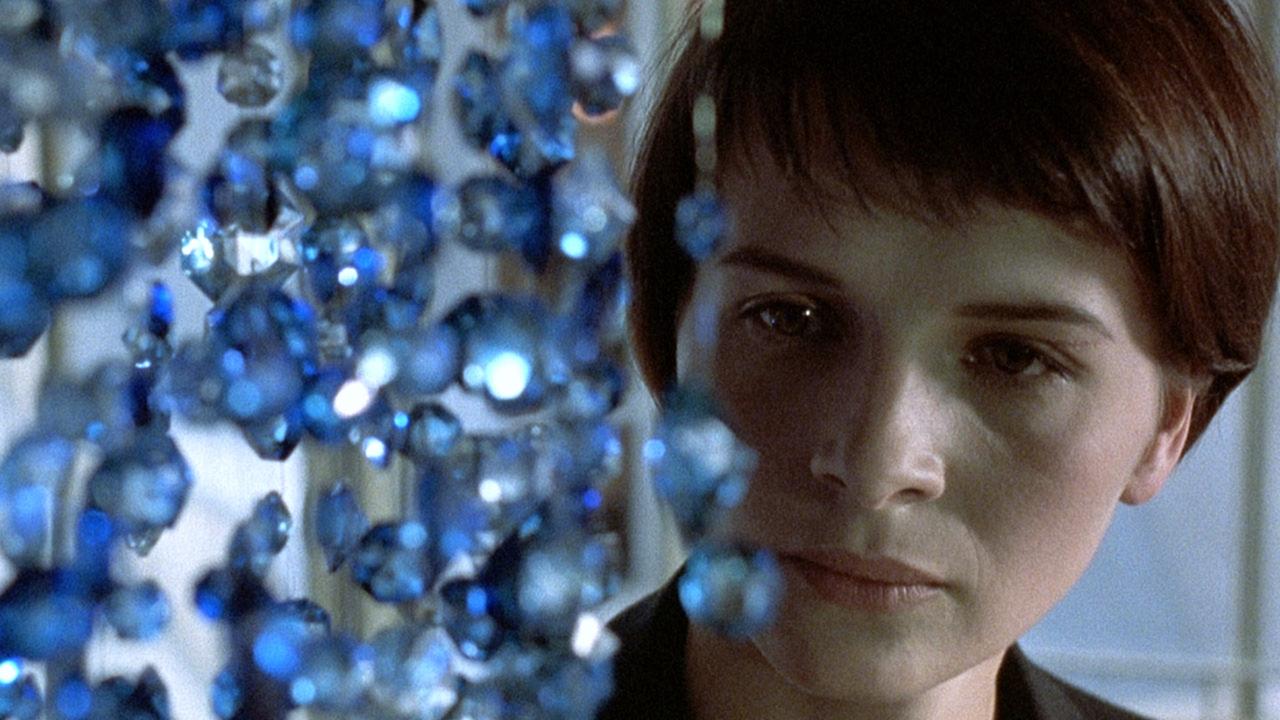

4. Three Colors Trilogy (1993 –– 1994)

Legendary Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieślowski’s dazzling Three Colors Trilogy will be appreciated by audiences and analyzed and enthusiastically discussed by critics forever, probably, and deservedly so. Playfully and profoundly inspired by the colors of the French flag, this daring cinematic triumvirate is as follows: Three Colors: Blue (1993), Three Colors: White (1994), and Three Colors: Red (1994).

And all three were co-written by Kieślowski and Krzysztof Piesiewicz (with story consultants Agnieszka Holland and Sławomir Idziak), have musical scores by Zbigniew Preisner, and of course were sensationally directed by Kieślowski. His coup de grâce and final filmic statement, Kieślowski retired after the trilogy, owing to health issues mostly (he died of complications after a heart attack in 1996).

Each film, as their titles suggest, emphasize a different color and emotional spectrum, also playing on the three political ideals in the French Republic motto: “liberty, equality, and fraternity.” And ever the subversive storyteller, each film in sequence have been rightly proclaimed respectively as “anti-tragedy, an anti-comedy, and an anti-romance.”

Assisted by first-rate cinematographers Slawomir Idziak (Blue), Edward Kłosiński (White), and Piotr Sobociński (Red), and of course a female-led dream cast (including Juliette Binoche, Julie Delpy, and Irene Jacob), these films cast a colorful glow that has only added in poignancy and power over the years.

“All three films hook us with immediate narrative interest,” wrote Roger Ebert. “They are metaphysical through example, not theory: Kieslowski tells the parable but doesn’t preach the lesson.”

3. In the Mood for Love (2000)

The use of color, texture and light is integral to the ashen ache of stolen moments, and the often painful passage of time which hangs heavy upon Wong Kar-Wai’s 2000 masterpiece, In the Mood for Love. As anthem to the agony and ecstasy of close-lipped affection, this film more than any other in Wong’s considerable oeuvre, is a Proust-like conjuration of memory and misgiving.

In the Mood for Love unravels in Hong Kong, 1962, centering on two neighbors living in a close quarters tenement house. Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung shimmer as Su Li-zhen and Chow Mo-wan, the neighbors in question, who rightly suspect their respective spouses are having an affair.

A painful poetry and sad resignation haunt the pair of potential sweethearts, elegantly framed by superstar cinematographer Christopher Doyle, Wong’s frequent collaborator (and props also go out to Pung-Leung Kwan and Mark Lee Ping-bin, who also collaborate in lensing this film, due to the lengthy shooting schedule which pulled Doyle prematurely from the project). Numerous times the camera seems to pry, eavesdropping almost, on the star-crossed couple and their resisted romance.

The period details are perfect and never perfunctory—the cheong-san dresses adorned by Su Li-zhen are heart-stirring in detail and design—the color saturation and play of light is heavenly and mnemonic as is the use of music which conveys and captures an unfeigned nostalgia. The bright colors –– the use of red adds a sensual and often smoky haze –– and unconventional compositions that Wong’s name became synonymous with in the 1990s is here faultlessly fulfilled, even when hemmed in.

As close to perfection as possible, In the Mood for Love renders on an intimate scale the intersection of misery and euphoria, of romance in retrospect, and makes it into cinema’s saddest song of love lost to history.

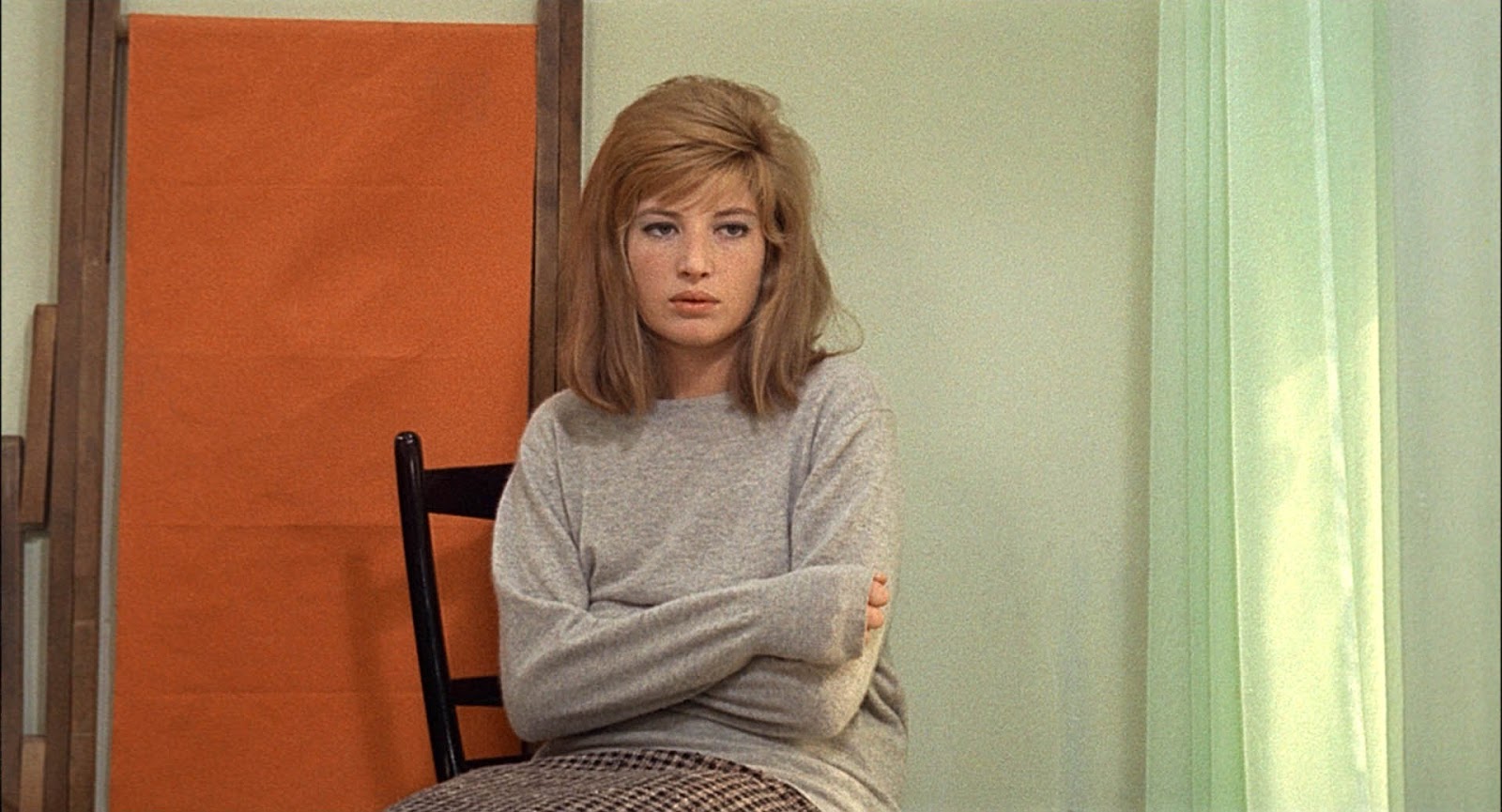

2. Red Desert (1964)

Michelangelo Antonioni’s first foray into color film photography, Red Desert is renowned and revered for its scenic design and galvanized complexion. Unspooling amidst the toxic factories and modernistic wastelands of Italy, Giuliana (Monica Vitti) is a wife and mother whose shaky grip on reality is ever slipping. Her vivid perceptions, her palpable alienation and steady growing unease is boldly asserted via the industrial landscapes and variegated ruins all around her––Antonioni famously had set painters add color to the scant flora and fauna as well as structures in the far background, to better emphasize Giuliana’s creeping concerns as her mental state spirals out of control.

Writing for the Daily Telegraph during the film’s original release, Robbie Collin wrote that “[Antonioni’s] bold, modernist angles and thrillingly innovative use of color (he painted trees and grass to tone with the industrial landscape) make every frame a work of art.”

One of Antonioni’s definitive works, as well as one of Vitti’s finest performances, Red Desert is a haunting horror of modern malaise and the color of society’s sickness and spiritual disintegration.

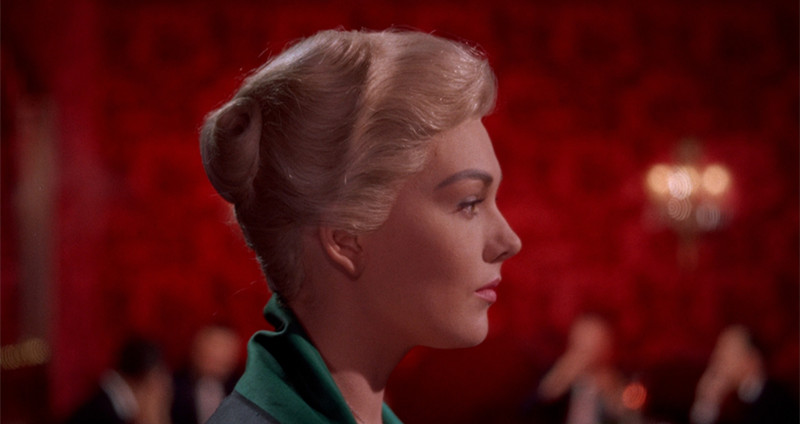

1. Vertigo (1958)

The chimeric use of color––has green ever depicted desolation and jealousy more succinctly?––adds to the tenacity and breadth of vision in Vertigo, often dubbed the most personal of Alfred Hitchcock’s films.

James Stewart is brazenly cast against type as John “Scottie” Ferguson, essentially an anti-hero, he only seems capable of associating with the world via his twisted and unhealthy obsession with a woman (Kim Novak) who is illusory––an inception meant wholly to entice him. After her death Scottie happens upon her double and degenerates into a controlling brute, a captive to his awful nature, and a slave to his unsound desires.

Hitchcock boldly reveals the nature of Novak’s dual roles as Judy and Madeleine early on in the film––though Scottie is left on the hook for quite a while––eschewing what 1950’s audiences would expect from a suspense thriller narrative, and the rich color spectrum visited upon the film add surreal layers that caught audiences off guard.

Perhaps Martin Scorsese put it best; “Whole books could be written about so many individual aspects of Vertigo––its extraordinary visual precision, which cuts like a razor to the soul of its characters; it’s many mysteries and moments of subtle poetry; its unsettling and exquisite use of color; and its extraordinary performances…” Vertigo is clearly a monumental and illustrious work from a master of the craft, and upon your next viewing take note of the kaleidoscopic colors that the Master of Suspense utilizes. You won’t be left cold, oh no.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.