5. Character Work

A great writer can add layers to all his creations, even if they feature in the story for a time and purpose largely of no significance, and even if they are not people, but the period or the landscape the story is set in. Complexity does not arise from knowing the deepest desires of the characters you create, but in knowing how their interactions with the world they inhabit influence those desires and how these desires shape that world.

Anderson realizes this in his films with the most indecorous amusement. He toys with his characters till they are fully in his control and he can make them dance to his gratifying beats. They remain as human as they were on the page, with their complexity intact. But they rise above the mundanity of being human to become parables and lore-like manifestations, something only a great director can do.

A majority of his work relies on the effectiveness of the ensemble of unhinged loners he assimilates to tell his story with. They complain and offer solace, they destroy and mend, they love and despise with an uproarious passion, all to great effect – their reality is palpable, and their consummate cinematic ability to sweep us off our feet makes for much more than just a good character study. They become elemental to our experience of the film and their delicately assembled triumphs and losses are inherited fully by us, without any questions asked.

Anderson’s characters reveal themselves to us in instalments, not just as the film covers its narrative sentence, but as we view them repeatedly. And yet, it is as if from the very first time we meet them, we are instantly aware of their dualities and their hypocrisies, as well their humanity.

We think know everything of Daniel Plainview the first time we see him in that mine hole – a man bound by greed, ambition and a twisted sense of duty and religion, but we are nonetheless educated in the richness of his existence every time we view the film. Our understanding may not advance any farther from knowing him completely from the very first shot of his dirty, mangled body in that mine hole, but our fascination keeps on growing.

4. Performances

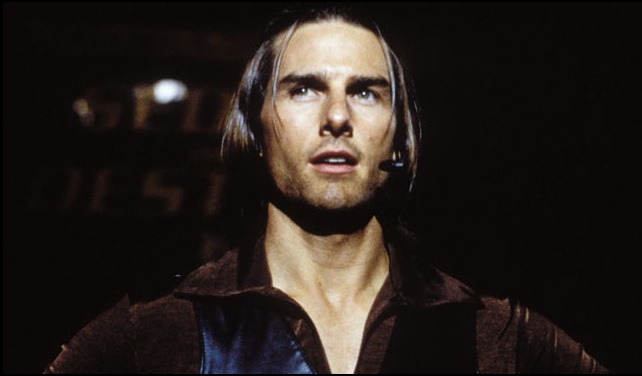

Each performer in a Paul Thomas Anderson film brings something to the table even they wouldn’t able to on any other film, let alone imagining anyone else doing it instead of them.

From the straight-faced, weary, tragically comical turn of Burt Lancaster in “Boogie Nights”, to the quietly self-assured and reassuring voice of Emily Watson in “Punch-Drunk Love” and perhaps more than anything else, the vulnerable, but unbroken sincerity of Philip Seymour Hoffman in “Magnolia”, even the side players are a flock of the most remarkable breed of actors, effortlessly giving some of the greatest performances of their lifetimes.

And then there are those whose work is not merely a milestone in their careers, but also in the art of film acting. Daniel Day-Lewis as the insatiable Daniel Plainview in “There Will Be Blood’, fixing his gaze on someone and conveying all of the character’s sense of pride, lust and the most humane self-doubt through his eyes or Joaquin Phoenix and Philip Seymour Hoffman as the master and devotee in “The Master”, both so violently, destructively and humanly in love with each other, seem to have broken the mould and brought in something entirely their own to the craft.

Anderson’s actors fully understand that it is essential not only to offer up the most honest realization of a character possible, but communicate in ambivalent, whispered terms the vision of the filmmaker. When Julianne Moore goes to fight her ex-husband in court for the custody of her son in “Boogie Nights”, the despondency she displays could not be more human, and then again, it is only as real as the urgency with which she finds a substitute for her son in a younger actress working in a production company while they both are on drugs. Does this exist only to satisfy the filmmaker’s singular, distorted vision or does it have real-life parallels? The answer to both is yes.

3. Experience over Realism

Cinema from the past few years has been, to say the least, highly informative. As we move farther away from the fantasy land of Old Hollywood in favour of grittier, grimier stuff, filmmakers keep going back to genres and stylings that made cinema a fuller, more pleasing experience than just portraying humans in ways that are true and relatable, but hardly work towards to serving your senses.

Musicals are popular once again, and so are intelligent, if slightly implausible science fiction as evidenced by the success of films like “La La Land” and “Ex-Machina” that on paper seem like difficult ideas to sell. All of this goes to show how as significant realism is to audiences today, we also yearn for the Old Hollywood extravaganzas that made us swoon – where experience was just as much a priority as telling good, real stories.

Paul Thomas Anderson is in relentless pursuit of presenting a most vital, complete experience in his work without compromising on a realistic depiction of human beings. A man destroys a restaurant bathroom, but all Anderson makes us think of is the woman waiting for him to return to their date outside because as real as the darkness that caused this man to vandalise the bathroom is, the woman who seems to be the only one to understand his isolation seems like a fantasy he, and by extension we, have somehow come to earn.

This preference of experience over realism makes Anderson a true stand out. In a time where documentaries are as good as feature films, if not better, he dares to make films that are in service to the audience – unabashed in their objective and masterfully crafted in every frame. There are details that make you vividly conscious of how relevant pleasing your senses is to the filmmaker. Meeting Owen Wilson in the fog isn’t half as funny on paper, but in Anderson’s smoke-filled obscurity, it’s also twice as mysterious.

2. Presentation of Time

Filmmaking uses time in a way no other art does. Films don’t happen in real time, even though there are some brilliant exceptions including Chantal Akerman’s masterpiece “Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles” that seems to happen in real time, and yet they seem to play with it in unknowable ways.

In Richard Linklater’s “Boyhood” which was shot over a span of 12 years, we see the same actors play the characters as they age over that period of time. In Andrei Tarkovsky’s “Mirrror”, or for that matter any of his films, time seems to be ultimate saviour, one that adds a much needed perspective to all misgivings so that we can hope one day to have no regrets.

In Paul Thomas Anderson’s films, time is of no consequence. His stories could be set in any place and any time and their universality would remain unscathed. Seeing him venture into period films has been an interesting experience, considering how intimate and surreally real even the most seemingly inaccessible of his settings are. Cults that took shape after World War II, oil rigs in the early 20th Century, or a drug-consuming investigator in the 1970s, all seem to be as human as motivational speakers, porn stars and casino owners and just as relevant to our understanding of the human condition, if not more.

Giving us a view of the distance between us and these characters in his period films by making the craft seem so dexterously authentic, he allows us to realise how truly stagnant humanity is, how not much has changed and not much ever will. Through the strikingly modern writing and acting in his films, he charts a shifts in our perception, mindfully crossing lines into our thoughts, and shaping them to hold history and all its gifts in a new, dangerously exciting light.

1. Ambiguity

Ambiguity is rewarded in literature. “What did it all mean?” is a question authors want to be asked. But unfortunately, more and more filmmakers are evading a chance to leave their work unexplained, crystallizing our perceptions to one single meaning, without letting various interpretations exist – one thing that ensures the longevity of a film’s life in discussions about cinema.

David Lynch has never felt it necessary to explain anything in his creations, and his most ardent fans have never felt the need to ask. Films are not puzzles to be solved, but a series of emotions to be felt and then be drawn to over and over. Pinning them down to one logical stream of thought is cruel to both the film and the audience.

Kubrick exploited ambiguity in ways so secretive, those determined to decode his films still have no clue on how to do it. With Lynch and Bresson and even Resnais, the ambiguity represented a greater theme for which multiple explanations are available, but with Kubrick that ambiguity could never be explained. It could be utterly devoid of any meaning whatsoever, or be a complex allegory. The only thing we can be sure of is how effective that ambiguity is. You respond it almost instantly, but you have no idea what you’re responding to, or what your response actually is.

Thus many consider “Eyes Wide Shut” to be the last truly ambiguous film – one that on the surface tells a simple story of a man and his wife in a troubled marriage, but beneath it can be about absolutely anything and everything a viewer wants it to be. Paul Thomas Anderson has managed to claim a spot in the Kubrick school of cinema and has inherited some of that electrifying ambiguity that we held such affinity for.

His films revel in the absurdity of their filmmaker’s humour, his sense of preciousness and his curiosity. They ebb and flow in their own pace, suffusing the narrative with a ballooning vastness that seems to both overwhelm and comfort you. You are in the hands of a seasoned filmmaker, but you have no idea what places he will take you. If we can agree on the assessment that Stanley Kubrick was the last great filmmaker, Paul Thomas Anderson will have to be content with being the greatest this generation has the fortune to have.

Author Bio: Anmol Titoria is a student at University and has been writing and engaging in many a parley about film since he was in school, where he was responsible for writing the film column of the monthly newsletter. He professes his love for Kubrick, Bergman and Tarkovsky in ways so multifarious and with such alarming regularity that his family has considered throwing him out repeatedly.