Due to its persistent economic instability and recurring social issues, Southeast Asia is a far cry from being a cradle of the world’s greatest cinematography. However, it was precisely these issues, coupled with a threat of censorship which is still very real in some Southeast Asian countries, that have given rise to a cinematic tradition that both embodied the best traditions of the European cinema and further developed them to better reflect the workings of various social institutions in a uniquely Asian environment.

Far from being a comprehensive guide to Southeast Asian cinema of the past few decades, this list aims to highlight the films that reflect the changes that each given country has undergone in the past. However distant these events may be, their repercussions are still felt today: in some places they are manifested in a sense of unease provoked by an overbearing control on the part of the state, in others it’s a general exaltation over the simple fact of having stayed alive.

1. The Story of Kindness or How to Behave (1987) dir. Trần Văn Thủy

The Story of Kindness is one of the hidden gems of 20th century post-war Vietnamese cinematography. Officially released in 1987, it was soon banned in Vietnam, but just after a few years critics began to look at it with a more favorable eye. The main message of the film – to look for kindness even when it seems that all goodness of the world has vanished – appealed to state censors who saw in the film the call for unification of people of Vietnam, and the ban was soon lifted.

On the surface, The Story of Kindness is a documentary about the aftermath of the Vietnam War. On a much deeper level, it is a poetic testament of another filmmaker, a friend of Trần Văn Thủy who, on his deathbed, urged his friends to “do something together, something that is inspired by human love.”

His deathbed wish soon becomes a quest for kindness in a country racked by war and poverty, and in the course of interviews with their fellow countrymen the filmmakers learn that kindness is always present in men’s hearts, even in the face of war, devastation, and death.

2. Cemetery of Splendor (2015) dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul

Cemetery of Splendor is a slow cinema masterpiece from one of the most acclaimed Southeast Asian directors, Apichatpong Weerasethakul. Those who enjoyed his first major feature, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, won’t be disappointed: Weerasethakul has not lost his touch with the social issues in Thailand, and his style has become even more imaginative and unconventional. As always with this director’s films, exegesis is possible only at the expense of some of the magic that lies in the nebulousness and mysticism of Apichatpong’s dream world.

The film revolves around the group of soldiers who are affected by a strange sleeping disease, and a few volunteers who help around the hospital located in the rural northeastern part of Thailand. When one of the volunteers, Jen, is given a clue to the real origin of the sickness (the hospital is built on an ancient cemetery), she begins to understand the battle each soldier is fighting in his dreams.

The film is thoroughly informed by the prevailing belief in ghosts and spirits, and because the belief is so widespread in Thailand, Weerasethakul’s treatment of the supernatural would send shivers down your spine.

3. The Floating Tomatoes (2010) dir. Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi

Of all Southeast Asian countries, Myanmar is the one where, until recent political changes, the notion of independent cinema was challenged by an overpowering state censorship and an almost complete lack of financial support. These circumstances, however, didn’t deter Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi from starting career as a filmmaker and human rights activist, and, in 2012, organizing The Art of Freedom Film Festival in Yangon, Myanmar.

The Floating Tomatoes may not be the most enlightening or illuminating watch. Indeed, very few people in the world would really care about the ecological issues that the farmers at Inle Lake face. The real achievement of The Floating Tomatoes, however, is its complete disregard for the political strife that had shaken the country and its economy. By shifting the perspective to the country’s rural regions and talking about the detrimental effects of pesticides on the biodiversity of Inle Lake, Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi left the past where it belongs and addressed the problems that Myanmar faced at the time and is likely to face in the future.

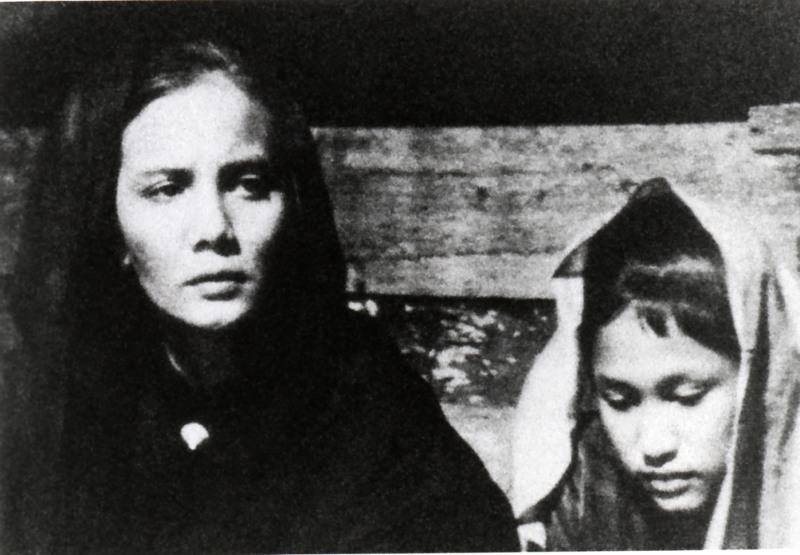

4. The Red Lotus (1988) dir. Som Ock Southiphonh

A part-time filmmaker and full-time baker, Som Ock Southiphonh is a Laotian independent director trained at the film school of Charles University of Prague. After returning to Laos, Som produced a number of short films commissioned by the state to promote tourism in Luang Prabang, but tired of this kind of work that left no space for creativity, he started producing his own films that were fully financed by his small bakery business in Vientiane.

The Red Lotus is a simple story of unfortunate young lovers that unfolds against the backdrop of nationwide violence, political turmoil, and personal struggle. As the two lovers are separated by the cruel father, the viewer is offered a front row seat in an epic narrative that combines images of war and peace, and contrasts the cruelty of political strife with what is supposed to be a peaceful life in the village.

But as the country undergoes a painful transition, the people are torn apart by the passions that leave no one untouched. For a movie shot on an old Soviet film camera, The Red Lotus is captivatingly beautiful, embodying both the best traditions of independent cinema and a uniquely Asian perspective on the role of an individual in history.

5. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul

For many, Uncle Boonmee, which won international acclaim after receiving the Palme d’Or in 2010, played the role of a benign Virgil on their journey through the uncharted terrains of Southeast Asian cinematography. However it would not be entirely appropriate to use Weerasethakul’s dreamy masterpiece as a definitive key to the region’s cinematic tradition.

It’s enough to say that even in his home country Apichatpong is not entirely understood, mainly because his unique style of storytelling is so deeply concerned with people — their beliefs, emotions, stories, and memories — that each film becomes a story-in-itself, which could only be experienced, but not understood.

A very slow but nonetheless breathtaking Uncle Boonmee tells the story of a man who decides to spend his remaining days with people (and spirits of people) he’d loved throughout his life. It’s a movie about leave-taking — but don’t expect to be a witness to tragic scenes and superfluous raging against the dying of the light. Rather: keep a concept of Reincarnation in mind and don’t be put off by visiting spirits and ghosts that seem ever ready to blur the boundary between the real and the imaginary.

6. Kinatai (2009) dir. Brillante Mendoza

Kitanai is a heart-rending story of a young student who unwittingly gets entangled in the secret dealing of Manila’s underworld. Despite the fact that the story is everything but novel, the film was received warmly by critics and even won the Best Director Award at the 62nd Cannes Film Festival, thus becoming the first Filipino film to have won so great a recognition from the international film community.

The protagonist, a young criminology student Peping, is about to get married. Yet his life is far from being settled: he struggles to finish his studies at the police academy and works at night. Driven to the edge of desperation, he agrees to do a small job for his friends whom he suspects of being associated with the capital’s underworld.

A short meeting at the park quickly escalates in a night-long tour though the city’s netherworld, during which Peping becomes an accomplice in a murder and a criminal on the run. The final minutes of the film would make you grind your teeth, as the young protagonist ponders over the seemingly watertight wisdom that ‘crime never pays.’

7. Tjoen Nja’ Dhien (1988) dir. Eros Djarot

Tjoen Nja’ Dhien is probably the most famous film to be produced in Indonesia, as well as one the iconic depiction of Southeast Asian (if not pan-Asian) struggle for independence after a century of colonialism. Directed and written by Eros Djarot, the film went on to win Best International Film at the Cannes Film Festival in 1989 and to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in the same year.

The film is set in early 1900’s, “the bloodiest years” of Dutch occupation. While the frail but unflinching Dhien is putting up a fight against the oppressor’s forces almost single-handedly, the perfidious leaders of the army are conspiring with the Dutch against her small but valiant regiment.

Bolstered up by the Islamic faith which the Dutch hadn’t quite eradicated from the warriors’ hearts, Dhien’s guerilla troops set in motion the machinery that eventually led to independence in 1945. Dhien’s character was inspired by Cut Nyak Dhien, an Indonesian leader who was active during the years of Resistance.