This is our second look at every Academy Award for Best Picture winner. In this instalment, we have entered the ‘50s. To compare to the previous winners, this portion will feature a larger percentage of films that are presented in colour.

The Hollywood Code is still affecting the content of the films of this time, and now filmmakers had to worry about the infamous Black Listing that caused mass hysteria; the latter actually affected winners of this decade, including the lowest film on this list. Politics would cause cinema to explode in retaliation, but that will be covered in the ‘60s and ‘70s rankings.

For now, movies were either vastly worsened by their inability to experiment, or the better filmmakers would find a way around these regulations and would go on to truly shine. Here are the ten Best Picture winners of the ‘50s in order from worst to best.

10. The Greatest Show on Earth (1952)

The Greatest Show on Earth? Spoiler: It isn’t. This ’52 disaster of a film is unfortunately this horrendous, since many huge names are attached here. You have Cecil B. DeMille in charge, Charlton Heston in an early role, Betty Hutton and Cornel Wilde in the line up, and James Stewart as a clown (of all things). Yes, this is the main issue with this entry: for a film that is so ambitious, it takes barely any of its attempts seriously. What exactly went wrong with this circus epic? The easier question is “what went right?”.

This beautiful train wreck (pun intended) includes gymnasts competing with some of the worst rear projection you will ever see, overacting at its damnedest, a subplot where a clown is permanently in his get up as he is a fugitive wanted for euthanasia charges, and a climactic train accident done with a model set and dolls that looks as fake as it can.

If you thought that run on sentence was longwinded, this cinematic irritation lasts for over two and a half hours. It is theorized that this film only won, because the Academy didn’t want a blacklisted director to win (Fred Zinnemann, whose films went on to win two of these awards nonetheless). The Greatest Show on Earth is anything but fun, and is a deceptive low point that should be avoided if you wish to check out the works of any of the above names.

9. Gigi (1958)

Having Gigi this low may seem sacrilegious, especially since Vincent Minnelli is a musical legend (his other Best Picture winner will be featured much higher on this list). Gigi is also a reasonably well crafted film to boot.

However, Gigi is this low for its excruciatingly dated ideas, its discrediting of the lead female character (the titular Gigi) who remained dependant on the snotty men in her life, and the ultimate fact that this film would be done much better (My Fair Lady, which also won the big prize in ‘64). Gigi has its strengths, but its faults hurt because of the potential that gets squandered.

Some of the musical numbers are endearing, but the majority of the characters being unlikeable just renders these songs forgettable. Some of the artistic ideas that are creative yet faulty include the deletion of sound altogether when a character walks into a room one scene to imitate the quieting down of a room (it just feels stale).

The men in this film are self absorbed, and yet Gigi fauns after them every time. Gigi is an entry here that is reflective more on how the film feels now as opposed to how it was as a product of its time. Again, there is a reason why My Fair Lady is brought up many more times nowadays than Gigi is (and so is An American in Paris, for that matter).

8. Around the World in 80 Days (1956)

In 2004, a remake of this adventurous film came out and did horribly with critics and audiences. It felt lame, hokey and uncontrolled. So, the original film must be immeasurably better, right? Here’s a revelation: it isn’t. Around the World in 80 Days is an interesting concept with an incredible execution aesthetically, and a poor attempt with its writing.

David Niven and Cantinflas are a duo that utilize the film’s three hour running time to win a bet (the title of the film). The build up to this is realistic and the start is luxurious. Then begin the major problems of the film, as the arrival in various locations results in an arbitrary stop off or an offensive visitation.

This film boasts a plethora of cameos (and there most certainly are too many), ranging from Peter Lorre to Frank Sinatra (whose face graces the screen for, wait for it, three seconds). The only thinkable purpose this serves is to temporarily entertain the audience for seconds a time.

When the cameos aren’t without a purpose, they’re grotesque, including an offensively-cast Shirley MacLaine as an Indian princess. A number of the geographical locations result in jokes that would not sit well today. The only major benefit to this film is the cinematography, which was so ahead of its time that many shots still feel exquisite. Aside from that, you are left with an insanely rushed ending that renders the majority of this three hour trip pointless.

7. From Here to Eternity (1953)

After the horrendous loss to The Greatest Show on Earth, Fred Zinnemann would eventually make up for his High Noon upset by winning twice; the first win was this war-romance-drama. From Here to Eternity is a strange film, as it seems to shift its focus quite often.

Are we to see the film about the army as a whole, Prewitt’s history as a boxer, Warden’s love affair, or the surprise ending where the attacks on Pearl Harbour take over the entire picture? There are a variety of facets in From Here to Eternity, and they all share an empathy for the loss of time in life.

Burt Lancaster, Montgomery Clift and Frank Sinatra are a triad of strong performances, and they are well accompanied by Donna Reed, Deborah Kerr, Ernest Borgnine (who is very against-type with this mean character) and more.

The cinematography by Burnett Guffey is quite ahead of its time, with excellent shots that cover the manic (the Pearl Harbour scenes) and the graceful (the legendary shot on the beach). All of Eternity’s parts may not smoothly fit together, but each segment is strong on their own, and they all cater to the same message: legacy surpasses the now.

6. Ben-Hur (1959)

The first film to win a record of 11 Academy Awards (Titanic and Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King would follow suit later), Ben-Hur is cinematic royalty. It is the last William Wyler film to win Best Picture, and it is his most well known film despite how distant of a departure it is from his usual works.

Ben-Hur is an epic in every sense of the word, including its extreme length, humongous sets, intense sequences and sprawled out plot lines. It is often brought up during discussions of classic films, but does it fully deserve to be?

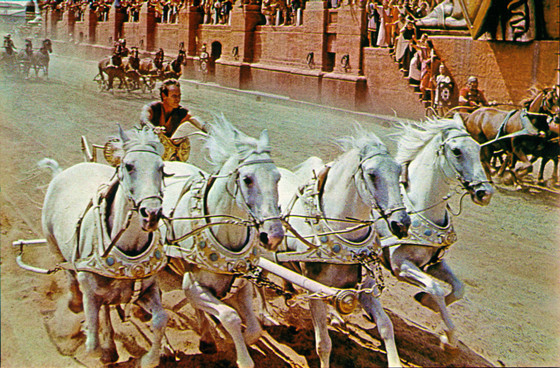

Charlton Heston’s performance is quite strong, and Stephen Boyd’s work should not be ignored either. The excessive length does take away from these performances, and so do the more outlandish characters (there is no way Hugh Griffith’s take on an Arabian Sheik would pass nowadays). There is the classic chariot sequence, as well as some other strong moments (the slaves rowing the ship, Judah Ben-Hur’s confrontation with Messala and more).

Weirdly, the film dives into a religious fable on Jesus Christ in the last quarter as if it were from an entirely different picture (religion and Jesus are featured throughout, but not nearly as much as the finale). There is a lot going on, yet it is all a bit muddled and confused. Ben-Hur will still remain as an Academy record setter no matter how it stands today as a standalone film.