5. The Sting (1973)

Is this film ever a wild ride. The Sting, like many entries here, has a highly appropriate title to label itself with. The film is woven together with hand painted title cards (along with that iconic ragtime music by Marvin Hamlisch), and the final card is the titular “The Sting”.

This is a con man’s caper, where we follow the escapades of Robert Redford’s Kelly and his attempts to pull the wool over Shaw’s (Paul Newman) eyes. Each player is a chess piece on the board of America; Newman is the King who works strategically in short actions, and Redford is a pawn with a small chance in hell of overtaking the situation.

As you follow the motives of every character, you think you will have the upper hand on the film’s webs of lies. Not so fast; just when you think you know the film, The Sting pulls one of the greatest twist endings of all time.

The title of the film is how it fools every single one of its viewers, and we all bought into it. We are all saps. David S. Ward’s screenplay is manic brilliance, and George Roy Hill’s directing acts as a decoy that pretends to not know the plan that is underway. It usually doesn’t feel good to be robbed, but The Sting is the ultimate cinematic form of deception.

4. The Deer Hunter (1978)

Michael Cimino’s bravura feature is a three hour test of patience. You sit at a factory, at a seat during a wedding, and on a hill during a final hunt for an hour. You spy on those that are getting married, the friends that are enjoying one last hurrah, and their drunken escapades. That is why the moment you are tossed into the hells of the Vietnam war will grab you by the throat until you are at a loss of breath.

The nightmares in The Deer Hunter just happen, and they never cease to exist once they begin. When you are forced to wait while the revolver is being loaded during one of the Russian roulette scenes, there is no looking away.

The humans here are as susceptible of death as the deer they chase. Leaving Vietnam is a tribulation, but having Vietnam leave these characters is impossible. Cimino’s greatest work is the result of slow burning, lightning fast pay offs and the regrets that linger longer than their build ups.

War plagues every person here, whether they are in the battle or at home. No one is left unaffected at the end of the three hours. If anything, The Deer Hunter may be one of the more difficult Best Picture winners to view because of how graphic it can be, but it is a tour-de-force that hasn’t been matched yet.

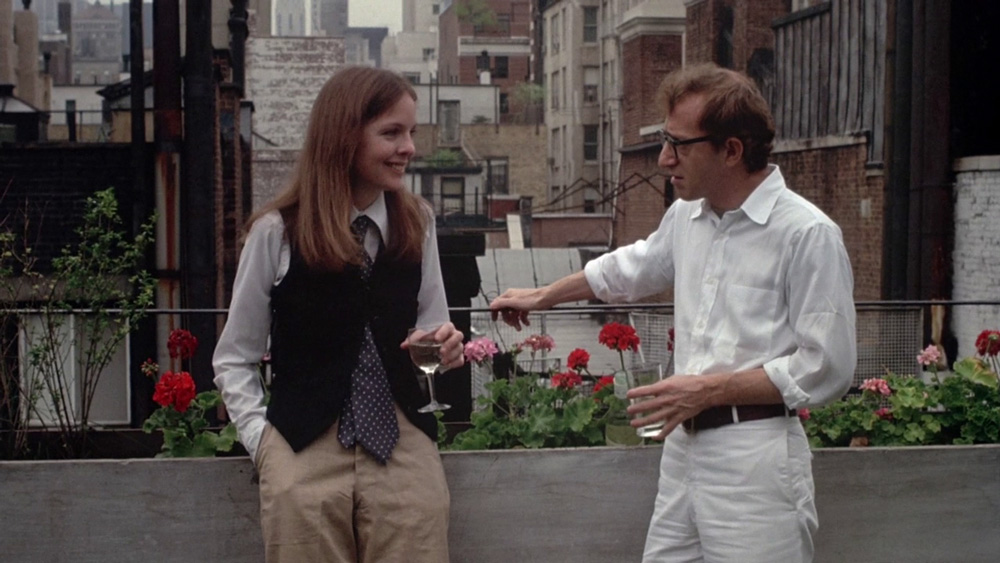

3. Annie Hall (1977)

Gone are the days where comedies could get away with being metaphysical rants within an anxious mind that trips over its own thoughts. Alvy Singer is a schmuck that lost his love, and we have to put up with his nostalgia. He entertains us by disguising his faults as personal victories (no director would come out of nowhere and defend your analysis on their film because that isn’t how life works).

Each memory is a sketch to remember each moment more fondly and personally. Annie Hall is a frantic recollection of Singer’s past, because they all return to her and what she meant to him.

The writing is some of the greatest comedic writing in history, as you have all sorts of humour to be entertained by. Jokes constantly break the fourth wall (because an extra pair of ears to listen is what Singer can use), sarcastic remarks line each scene like a border, and there is even an occasional slapstick shot to enjoy Singer’s pain.

The ending line compares the scenes of one’s life to eggs, and that moment was created mere moments before the film was completed for a test audience. If that doesn’t remind you that Annie Hall was a neurotic catharsis for Woody Allen.

2. The Godfather (1972)

A dispute that often takes place is which Godfather film is the best; this argument usually rests on the shoulders of the first and second films, as the third is usually (willingly) forgotten about. Both films did a great job bringing Mario Puzo’s story to life, as the greatest cast in film history lived and breathed these perfectly sculpted characters past the questionable point of reality.

The first film is featured here in a marginally lower position than the second, but that does not necessarily make it an inferior film. It achieves its own successes, like setting up this terrific story, introducing the cast of players, the complexities of the Corleone family and building the private lives of gangsters. Marlon Brando’s “can’t refuse” line gets brought up so often in conjunction to this picture, probably because it is so difficult to single out any particular moment of this movie otherwise.

Well, you could bring up the teeth-grinding scene, the toll booth heart attack, or the Apollonia stomach twist. You could remember these scenes, but they are usually much more bearable in context, as these memories will shake you up as if you are viewing the film without the safety of knowing you are currently watching it.

The Godfather implants lines, scenes, and faces better than almost any other movie imaginable. Cabaret won more Oscars that year (including a director award for Bob Fosse), but it would be an absolute crime to pick any film above The Godfather (and that wasn’t because Tom Hagen was on the Academy’s welcome mat).

1. The Godfather Part II (1974)

The Godfather set up the story of the Corleone family, but The Godfather Part II furthered the growing branches and roots of the family tree. It jumped back to the past to relive the harrowing histories of Vito Corleone’s youth. It cuts to the present to witness Michael Corleone’s continuing descending into hell. Both Vito and Michael, in different points of the Corleone timeline, have to reclaim their integrity to guarantee the safety of their loved ones.

With Vito, family was to be rescued and expanded. With Michael, family had to be sorted through to see who put their entire legacy at stake. The Godfather Part II is both a sequel and a prequel; whichever one you wish for it to be, it reigns as one of the best sequels and/or prequels ever.

Al Pacino’s continuation as Michael Corleone is some of the most detailed acting in history, and Francis Ford Coppola used the same attention-to-detail to make the second film a seamless transition from the first (despite the two separate stories).

This part leaves the comforts of New York to Miami and Cuba, where Michael tries to regain his control. This second instalment even furthers the storylines of minor characters, including the mighty return of Connie (who, like the rest of us, never forgot what happened at the end of the first Godfather).

This film is placed higher than the first movie, because it fulfilled the impossible. It bettered parts of its predecessor, became as necessary as the first part, and it even ended up winning more Oscars (including, finally, a Best Director win for Coppola). Excluding The Return of the King, a sequel will likely never win Best Picture again (never mind the fact that both instalments won).

Rankings of other decades:

Pre-1950 Best Picture Oscar Winners Ranked From Worst To Best

1950s Best Picture Oscar Winners Ranked From Worst To Best

1960s Best Picture Oscar Winners Ranked From Worst To Best

Author Bio: Andreas Babiolakis has a Bachelor’s degree in Cinema Studies, and is currently undergoing his Master’s in Film Preservation. He is stationed in Toronto, where he devotes every year to saving money to celebrate his favourite holiday: TIFF. Catch him @andreasbabs.