7. Fear(s) of the Dark (Blutch, Charles Burns, Marie Caillou, Pierre Di Sciullo, Lorenzo Mattotti & Richard McGuire, 2007) / France

Fully animated horror anthologies are as rare as hen’s teeth, even amongst seinen anime, so “Fear(s) of the Dark” comes across as pretty unique. It represents a remarkable effort of six artists from France, Italy and the USA who gather to bring their more-or-less macabre visions to the silver screen, “in luminous whites, pulsing blacks and gorgeous grays”, as Jeannette Catsoulis puts it in her review for the New York Times.

Pierre Di Sciullo provides hypnotizing, “wrap around” intervals of geometric abstraction during which we listen to a woman expressing her fears through the shrink couch-like monologue. These parts address many contemporary anxieties and they are the most experimental, yet least scary.

Christian Hincker known as Blutch goes for a gritty style with his grim, Piotr Dumała-esque satire (of capitalism?) which portrays a skinny, sinister nobleman who roams the countryside, unleashing his four bloodthirsty hounds, one by one, on unsuspecting victims. From his graphic pen emerge the intricate, quivering lines interlaced with dread itself.

In a hyper-stylized CGI vignette drenched in thick, jagged shadows, Charles Burns explores sexual insecurity and unhealthy obsession. So, he focuses on an intelligent introvert, Eric, whose interest for insects is subverted in a romantic relationship which begins sweetly, but gradually turns into the entomologist’s hell.

The only girl in the team, Marie Caillou, draws inspiration from the Japanese folklore and delivers the most grotesque segment structured as a bad dream within even worse dream. Her heroine, a traumatized schoolgirl called Sumako Ayakawa, is receiving a dubious clinical treatment for her nightmares in which she is severely bullied by her classmates and haunted by a samurai ghost. A few hints of (bloody) red (the film’s only color intrusion) cut through the monochrome imagery like a knife.

Following Caillou’s “anime faux” is Lorenzo Mattotti’s eerie, charcoal-illustrated tale of deliberate pace and smooth transitions in which childhood memories meet rural superstitions. Its fine, grainy texture adds an extra layer of fear to the proceedings.

And the blackest for the last is Richard McGuire’s take on a haunted house story. Dialogue-free and rendered in simplistic, yet effective chiaroscuro compositions, this unnerving mystery is more Poe-esque than Raul Garcia’s “Extraordinary Tales”.

8. North Dragon (Riho Unt, 2007) / Estonia

If you like your (short) films odd and puzzling, then “North Dragon (Põhjakonn)” is definitely the one for you. Adapted from the fairy tale “Toad from the North” as recorded by Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald (who is considered the father of Estonian national literature), this surreal fantasy leaves you scratching your head, no matter how many times you see it.

According to the official synopsis, it depicts the story of a young soldier who saves the world from the titular monster, with the help of a mythological virgin from hell, Põrguneitsi. When he comes to understand nothing has changed for the better, he leads the world to ruins again.

Riho Unt goes for a lyrical narrative, reducing the dialogue to a minimum and relying upon his art of puppet mastery. Blending the extraordinary stop-motion animation with a few dreamlike live-action sequences that almost appear as a ballet performance, his work feels like some deconstructed folk legend – mystical and rich with symbolism.

Modeled with great care, a mischievous jester, voracious kings, two ragged crows (looking like they wandered off the set for Jim Henson’s “The Storyteller”) and our hero in his doll form pop out of the dirty white scenery resembling the antique ruins. Thanks to his DP Urmas Jõemees’s keen eye, every shot is worthy of being framed and hung in a gallery.

9. Alice’s Birthday (Sergei Seryogin, 2009) / Russia

Based on the 1974 book from Kir Bulychov’s children’s series “Alisa Seleznyova” (1965-2003), Sergei Seryogin’s feature-length debut revives Soviet science fiction via its retro-styled animation in the vein of Roman Kachanov’s (highly recommended) “The Mystery of the Third Planet (Tayna tretey planety, 1981)” which is also the adaptation of Bulychov’s work. The story is set at the end of the 22nd century and it chronicles the the titular heroine’s exciting time-travelling adventure.

A curious and mischievous daughter of a space-zoologist Seleznyov, Alice fails her history exam (on the subject of Ivan the Terrible) one week before her birthday, while causing the ruckus in the classroom with her squid-like pet. However, she decides to keep her bad mark secret to herself and share it only with her father’s four-armed Chumarozian friend Gromozeka who presents her with the trip to the newly discovered dead planet of Coleida.

Once there, the members of the expedition learn that the population was wiped out by the unknown plague a 100 years ago, so Alice and an alien scientist, Rrrr, who looks like a one-eyed cat, travel to the past in order to prevent it from spreading.

Although we all know the film is going to end on a happy note, even when Alice is faced with the (ostensibly) insurmountable obstacles, Seryogin manages to keep us involved and entertained, as well as charmed by the quaint and colorful artwork. Seamlessly blending classic and computer animation, his team achieves the look of some odd 70s picture-book come to life, with the vivid, boldly lined characters popping out from the “velveteen” backgrounds. If you want to awaken your inner child (and geek), don’t look any further.

10. Cages (Juan José Medina, 2009) / Mexico

Nine years after his excellent debut – a stop-motion horror “The Eighth Day of Creation (El octavo día de la creación)”, Juan José Medina delivers another fascinating miniature – an allegorical post-apocalyptic fantasy “Cages (Jaulas)”. It portrays “a cycle of abuse and exploitation in the midst of desolation”, according to the official synopsis, whereby its bizarre protagonists are shrouded in mystery.

At the beginning, we see an old man wandering the desert, while carrying several wooden cages on his back. With a gold coin in his left hand, he makes the sign of a cross, before a sudden sandstorm frees one of his captives – a cherub with a child’s face, mellifluous voice and bare backbone as a tail – and changes his life forever.

Once again collaborating with the cinematographer Sergio Ulloa and the art director Rita Bastulto, Medina demonstrates enviable skills and proves to be worthy of comparison to the likes of the Quay brothers or even Jan Švankmajer. Speaking through the striking imagery accompanied by Alfred Sánchez Gutiérrez’s haunting choir score, he relies upon León Fernandez’s creepy, meticulously crafted puppets whose icy gaze reflects the bleakness of the fictitious future.

In addition, the palette of “withered” colors dominated by earthy tones intensifies the discomforting atmosphere of despair and inevitability.

11. Eleanor’s Secret (Dominique Monféry, 2009) / France | Italy

“Nobody can live without dreams.”

To make sure we remember these words, Dominique Monféry of “Destino” fame creates a lovely and lavish G-rated adventure in the “Honey, I Shrunk the Kids” style, sending all the right messages to the kids and reminding the grown-ups of their childhoods.

The main protagonist is a seven-year-old dyslexic, Nathaniel, who moves to his great aunt Eleanor’s beach house, together with his parents and older sister, Angelica. There, he learns that the late and even in her death eccentric spinster Eleanor left him her enormous book collection, which is “like giving reading glasses to a blind person”, in Angelica’s words.

Accidentally, Nath discovers that the library shelters all the children’s literature heroes who believe that the boy is their new protector. They need to be guarded, because leaving their home would cause them to disappear along with their stories, forever and ever. So, it’s up to Nathaniel (shrunken by Carabosse, aka Maleficent) to save his miniature friends once a sly antiquarian decides to take advantage of the family’s difficult financial situation.

Shrouded in soft textures, “Eleanor’s Secret (Kérity, la maison des contes)” boasts charming and colorful animation complemented by the evocative score and admirable voice-acting, with much warmth exuding from each frame. And you can almost smell old paper and feel the magic while sliding down the rabbit hole…

12. Sintel (Colin Levy, 2010) / Netherlands

In a snow-covered mountain, a young, daring and persevering girl, Sintel, is attacked by a bald warrior, but she manages to beat the odds and defeat him, falling unconscious in the aftermath of their battle. A benevolent shaman brings her to his cabin where she tells him how and why she got there.

Through the flashbacks, we are introduced to Sintel’s past and her friendship with a wounded dragon cub who has been taken from her by its hostile “cousin”. Determined to get it back, she sets on an arduous and perilous journey in desert and wilderness…

Together with his screenwriters Esther Wouda and Martin Lodewijk, Colin Levy spins the story of considerable emotional power, combining action, fantasy and drama. He makes the most of the film’s short running time and successfully brings believable characters to life, not shying away from showing blood and death, unlike many of his contemporaries prone to sugar-coating. Originality may not be his forte, but his brainchild comes as a well-tailored piece of CGI cinema.

Technically speaking, “Sintel” is eye and ear candy, boasting admirable character and background design rich in details, as well as beautiful, Celtic-esque melodies perfectly fitted for the alternative medieval setting. Also praiseworthy is the voice work by Halina Reijn and Thom Hoffman (who both starred in Verhoeven’s “Black Book”). On top of that, each scene is carefully thought-out and superbly directed.

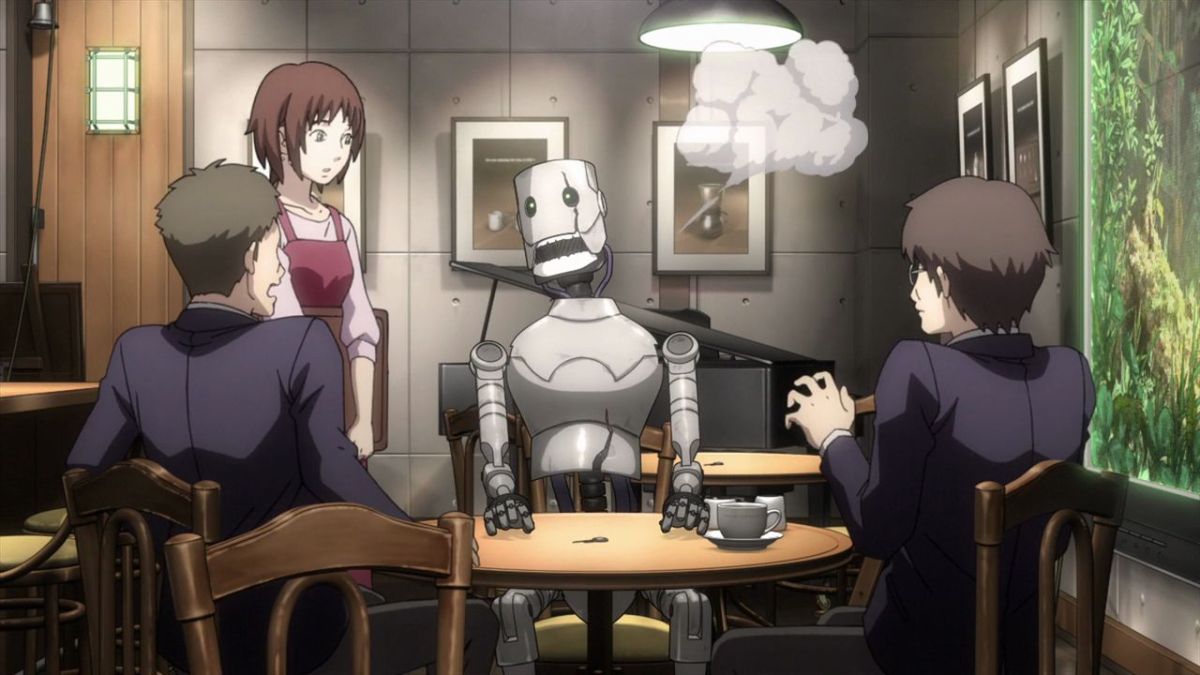

13. Time of Eve (Yasuhiro Yoshiura, 2010) / Japan

The title of Yasuhiro Yoshiura’s debut feature refers to a cozy coffee house wherein humans and androids alike can spend some quality time, without the latter being labeled by holographic “halos” they are obliged to display elsewhere. At that very place – a discrimination-free zone, one middle schooler named Rikuo will learn that you don’t need a body of flesh and bones to be able to feel.

“Time of Eve (Eve no Jikan)” merges the six episodes of the eponymous ONA (abbr. from original network animation) and, together with a few additional scenes, brings the final revision of the story conceived in “Aquatic Language (Mizu no Kotoba, 2002)”. The not-so-distant-future setting that sees synthetic organisms serving our needs is certainly not a novelty, but this sci-fi slice-of-life- dramedy is a different, tame and cuddly beast.

Its relaxed, optimistic atmosphere is so refreshing that you wish “Eve no Jikan” really existed, so you could go there and chat with its barista Nagi or its regulars, while enjoying a cup of warm drink. And it is thanks to the tight script and great cast of seiyuus that the protagonists – each having some small quirk – appear as quite convincing. But the best thing about them and their tale is the absence of the “AI independence leads to a devastating conflict” cliché.

The film excels in the audio-visual department as well, with the specific artwork and soft, pleasant colors, unusual “camera work” and mellow score that makes it an anime equivalent of a talented pianist concert.