The powerful and tragic effects of psychological trauma truly entered the consciousness of mainstream America as veterans were returning from the Vietnam War. This prompted the American Psychological Association to finally recognize Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as an actual affliction in 1980.

Prior to this new diagnosis, terms like “shell shock”, “combat fatigue”, and “hysteria” were used to describe the bevy of short- and long-term symptoms that patients often felt after experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event.

While the diagnosis of PTSD did not exist until the early ‘80s, authors and filmmakers had been exploring the horrifying and detrimental impact of psychological trauma for decades. As is the case with trauma, film has represented the varied and unpredictable symptoms that manifest in sufferers.

Additionally, through the years the film industry has captured the wide array of events and situations that can leave a permanent scar on the psyche. While some portrayals have bordered on melodramatic and over-the-top, many others have been subtle and nuanced in their approaches.

1. Deer Hunter (Michael Cimino, 1978)

When looking at the history of trauma in film, it becomes clear that this entire list could be made up of nothing but war films. As mentioned above, war truly served as the catalyst for the recognition of PTSD. That being said, Deer Hunter stands out amongst the catalogue of other traumatic war films in its scope, tension, and weight.

Deer Hunter is set from a span of 1967-1975 in both a working class town in Western Pennsylvania and in Vietnam at the height of the war. It follows three friends Mike (Robert DeNiro), Nick (Christopher Walken), and Steven (John Savage), as they prepare to ship out, serve in the war, and deal with the emotional aftermath.

The film is most known for its harrowing depiction of the group’s experience as POWs, where they are forced to play Russian Roulette for their captors’ gambling entertainment. While these excruciatingly tense scenes drew criticism for their apparent inaccuracy, they provide the audience with the proper context to believe the devastated emotional health of the three friends.

The greatness of Deer Hunter’s portrayal of trauma is that it examines the ways that different people can be affected in different ways by the same event. Mike wants to remain invisible and seems unable to view his friends and his old life the same. Steven, who is also physically damaged, is a shell of his former self and goes into hysterics at the thought of returning to his wife and home.

Nick goes AWOL in Vietnam and begins a “career” playing Russian Roulette for money. He is unable to remember his home or friends. In fact, Deer Hunter takes the effect of trauma even further by showing how the wives and girlfriends of the returning veterans are vicariously scarred through their loved one’s tragedies.

2. The Fisher King (Terry Gilliam, 1991)

There is nothing subtle about the films of Terry Gilliam. His wild set designs, costumes, camera work, and characters all lend to a frenetic film viewing experience.

This is very much the case with his representation of psychological trauma in The Fisher King. The Fisher King begins with shock jock radio host Jack Lucas (Jeff Bridges) inadvertently motivating a listener to commit a mass shooting in an upscale restaurant.

In the years that follow, Jack loses his career and becomes a suicidal alcoholic. He is rescued by a highly neurotic homeless man, Parry (Robin Williams in all of his wonderful excess), as he is being randomly attacked one night. Jack seeks personal redemption by trying to help Parry find love and a more stable existence, after he learns that Parry is the way he is because he witnessed his wife’s murder.

Parry’s trauma is represented largely through his own hallucinations. He believes he is on a quest to find the Holy Grail and that Jack is a knight who will help him. He envisions a Red Knight that aims to prevent this quest from being completed. Parry also experiences stretches of catatonia that leave him in a coma-like state.

The clean resolution at the end may take away from the authenticity of the experience of trauma, but the eclectic tone and Gilliam’s beautifully weird visuals help capture the hallucinatory feel.

3. Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (Zacharias Kunuk, 2000)

The first full-length Inuktitut-language film ever produced, Atanarjuat recreates an Inuit legend involving multigenerational trauma. The film was celebrated upon release for using predominantly Inuit actors and crew members, filming entirely on location, and bringing the oral heritage of a largely ignored people to light. The plot of Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner centers around a curse placed on the village of Igloolik.

As decades pass and several village leaders face untimely deaths, the story shifts focus to brothers Amaqjuaq (Pakak Innuksuk) and Atanarjuat (Natar Ungalaaq) and their feud for leadership with Oki (Peter-Henry Arnatsiaq). Atanarjuat escapes an assassination attempt from Oki that kills his brother, although he is badly injured in the escape. After recovering from his injuries in a neighboring village, Atanarjuat returns to Igloolik to regain his power.

The trauma developed in Atarnajuat: The Fast Runner is essentially the inherited trauma passed down through generations when people are unable to let go of past grievances and tragedies.

Each successive generation is consumed by pain and hardship through the constant presence of the tragedies of their ancestors. It is not until Atanarjuat takes a position of forgiveness, acceptance, and reconciliation, the he and the village are able to overcome.

4. Marnie (Alfred Hitchcock, 1964)

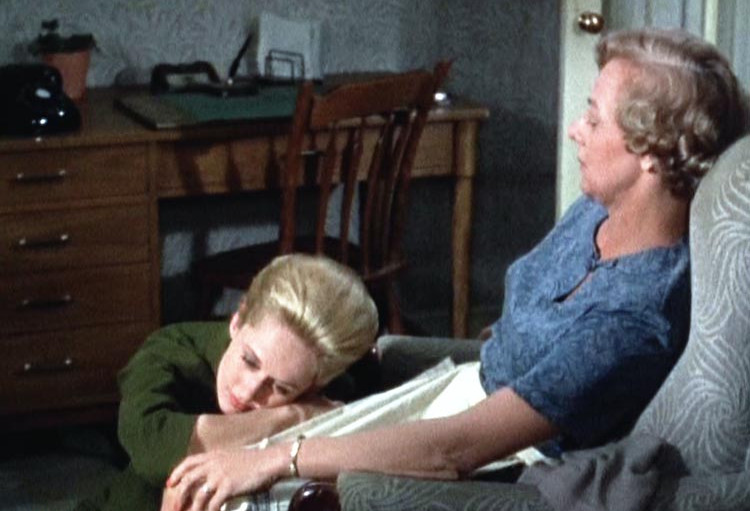

This classic Hitchcock film stars Tippi Hedren as the titular character, who presents one of the first female-centered stories of trauma onscreen. Marnie uses her beauty and charm to take advantage of men, mostly through getting hired and then embezzling money.

After she is caught in the act by Mark Rutland (Sean Connery), she is blackmailed into marrying him. As Mark learns more about Marnie, her intriguing past and paralyzing phobias come to the forefront.

Mark eventually tracks down Marnie’s mother and through their interaction the source of Marnie’s trauma is revealed. As a young girl she was molested and accidentally killed her assailant as he fought with her mother.

The emotional constriction brought on by this event caused Marnie to block out the memory. She additionally developed a crippling phobia of the color red, spawning from the blood she spilled. Here, the inability to process a singular traumatic incident, and the results of its aftermath, are the central focus of the traumatic representation. Viewers see how this one event shaped this woman, in largely negative ways.

5. The Magdalene Sisters (Peter Mullan, 2002)

The Magdalene Sisters chronicles the all-too-true tragedy of ‘impure’ or ‘fallen’ women who were placed in Catholic-run asylums for unwed pregnancy, prostitution, or perceived promiscuity. While these asylums spread throughout the former British Empire, they did not officially close their doors in Ireland until 1996.

The film follows four women as they endure brutal living conditions and sadistic abuse from clergy members. The women – Margaret (Anne-Marie Duff), Bernadette (Nora-Jane Noone), Rose (Dorothy Duffy), and Crispina (Eileen Walsh) – are humiliated, beaten, and sexually assaulted.

The Magdalene Sisters does not shy away from showing the viewer the source of the women’s trauma. The suffering of the women as they are enduring their abuse is clear. They, at times, emotionally break down and are unable to function. In other instances, they become shells of themselves and appear devoid of emotion.

While three of the women appear to have happy endings by escaping their tormentors, Crispina represents the debilitating legacy of the abuse. She remains institutionalized for the remainder of her short life, until she dies of anorexia at 24.

6. Coming Home (Hal Ashby, 1978)

Another entry stemming from the Vietnam War, Coming Home focuses entirely of the after-effects of living through an active war zone. The central protagonist is Sally (Jane Fonda), who reconnects with Luke (Jon Voight) while her husband Bob (Bruce Dern) is deployed. Luke also served in Vietnam and has recently returned home as a paraplegic.

Sally and Luke strike up a deep friendship that eventually turns into romance. When Bob returns home, wounded both physically and mentally, Sally is torn between the two men.

Coming Home, like Deer Hunter, shows how war-related trauma impacts veterans differently. Luke is highly bitter about his injuries and becomes active in the antiwar movement, channeling his pain into the resistance and his new relationship with Sally. It is implied that Bob intentionally injured himself to get out of the war.

When he comes back, he is more introverted than before, and when he learns of the affair he becomes violent and emotionally unhinged. The timeliness of this film, in coinciding with the America’s initial understanding of PTSD, makes Coming Home an important contribution to the narrative around trauma.