7. Luis Bunuel – Belle de Jour (1967) – Pierre can walk again, ending scene

Towards the beginning of his career, Spanish filmmaker Luis Bunuel was at the cinematic centre of the surrealist movement of the 1920s, with his short film Un Chien Andalou and first feature film L’Age d’Or both being pioneering works in the world of surrealist art.

Nearly 40 years later, Bunuel was still maintaining the surreal aspect of his cinema, however in different formats; from the avant-garde experimental films of the 20s, Bunuel became an internationally renowned filmmaker, and explored various film forms including melodramas, fantasy and comedic satire. His 1967 work Belle de Jour can be said to explore all of these genres, with the final scene of the film also showing signs of Bunuel’s surrealist roots.

Dreams are interspersed throughout the film, with Severine Serizy regularly dreaming to be involved a brutal sadomasochistic experience, rather than be married to her unfulfilling husband (Pierre). However, after a violent shooting from Severine’s extra-marital lover, Marcel, Pierre is left in a paralysed state that results in Severine’s guilt and dependency.

The final scene, a dream from Severine’s point of view, involves Pierre rising from his wheelchair and becoming healthy again, and finally, the couple are happy. Ambiguous and purposefully unexplained (typical Bunuel) the scene provides an analysis of both people’s sexual desires, as well as the moral state of the bourgeois class – a key theme in Bunuel films.

The melodramatic nature of the work allows the dream sequences to act as surrealistic portrayals of inner feelings and desires, showing the techniques of Bunuel’s earlier career and creating a final scene that shows not only Bunuel’s talent as a surrealistic filmmaker, but also as a dramatic and international one.

8. Andrei Tarkovsky – Nostalghia (1983) – 9 minute candle tracking shot in the pool

A cinematic poet, Andrei Tarkovsky has garnered both commendation and criticism for his uncompromising, unique and visionary filmmaking – some have labelled him an artistic genius, whilst others since have accused him of being self-aggrandising, idiosyncratic and disengaging.

Regardless of this, there is no doubt of Tarkovsky’s influence as a genuine auteur, whose recurring motifs of nature and metaphysical themes are seen without fail in all of his films, and especially in the empty swimming pool scene in Nostalghia.

As Andrei (the main character can be said to reflect Tarkovsky himself, a reoccurrence throughout his filmography), cautiously walks in the basin of the empty pool, he attempts to protect a small candle in his hand from going out before he reaches the other side.

In total the single shot is 9 minutes long, which even for Tarkovsky, is extraordinarily lengthy, creating a sense of real time and putting an importance on every detail in the scene; true aesthetic allure. From a symbolic point of view, the scene is also full of Tarkovskian representations, such as the candle portraying the central character’s life, and his attempts to keep the candle lit as the struggles he has faced.

The scene questions not only existence but the nature and purpose of it – a question which Tarkovsky was attempting to cinematically answer throughout his career until his premature death in 1986. Ingmar Bergman once said of Tarkovsky that he “invented a new language” in cinema, and through scenes like the “9 minute empty pool shot” in Nostalghia, it is evident that he certainly did.

9. Paul Thomas Anderson – Boogie Nights (1997) – Murder/ suicide at the porn party

Possibly the most reputable and original contemporary American filmmaker currently, Paul Thomas Anderson – in only 7 feature films – has created a distinguished style that shows heavy influence from great American directors before him, including Kubrick, Scorsese and even Orson Welles.

The kinetic camerawork of Scorsese, which PTA has made a regular technique in his own films, can be seen throughout the “Murder at the New Year’s Eve Party” scene in 1997’s Boogie Nights; a decadent yet disturbing insight into the Golden Age of Porn in the 70s.

The shot tracks “Little Bill” (played by William H. Macy, a frequent collaborator with PTA), who, after finding his wife cheating on him numerous times in humiliating circumstances, finally snaps. Flawed, dysfunctional and alienated characters are consistently portrayed in PTA’s works, and the mental torment his wife imposes on Little Bill finally takes its toll, resulting in the murder of his partner and his own suicide.

Throughout this, PTA’s bold visual style and use of accurate 70s costuming and set design enhance the aesthetic of the scene, with “Do your Thing” by Charles Wright playing in the background – PTA is known for his use of effective music in important scenes, and he executes it perfectly in this one.

Perhaps not the most narratively important scene, with the character of Little Bill being a relatively unimportant subplot, however it is certainly a memorable one that shows all of Anderson’s directorial facets to the highest pedigree.

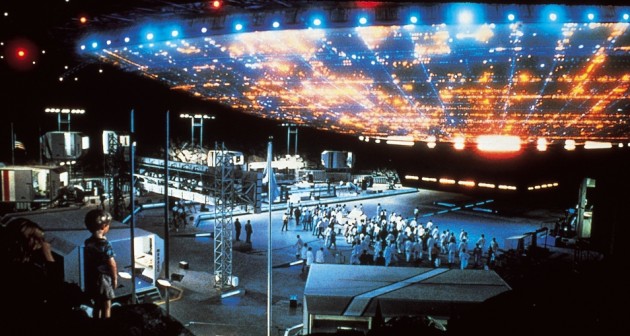

10. Steven Spielberg – Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) – Roy’s first encounter

After grossing over $9 billion worldwide from his films, Steven Spielberg remains the undeniable king of the box office, as well as a chief institutor in the development of the modern American summer blockbuster. His escapist explorations of cinema, especially in the science fiction genre, have helped him rise to the top of the directorial elite, and create some of the most popular and memorable films of the late 20th century.

This includes 1977’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind; Spielberg’s first sci-fi venture. Richard Dreyfus (a Spielberg regular) plays Roy, whose first encounter with the “third kind” undoubtedly sticks in the mind of all 70s children and sci-fi fans.

Blinding lights and gravity defying forces inundate Roy in his car, until the mysterious chaos stops and, in complete silence, Spielberg does what he does best – the big reveal. A large, overwhelming UFO appears from the sky, with Roy gazing up in awe and shock at the absurdity of the situation.

Despite Spielberg’s most frequent collaborator, John Williams, not being put to full effect in this scene, his presence is felt throughout the film and the scene itself epitomises the majority of Spielberg’s filmography, especially during the 1970s and 80s; the portrayal of fantasist worlds and memorable scenes through the use of high quality special effects, big reveals and most importantly, relatable, engaging characters that we can all see ourselves within.

11. Quentin Tarantino – Pulp Fiction (1994) – Ezekiel 25:17

One of many memorable Quentin Tarantino scenes, Pulp Fiction’s Ezekiel 25:17 monologue is perhaps the most revered of all. In a filmography full of iconic dialogue and controversial graphic violence, Jules’ thunderous religious rant showcases Tarantino’s unique blend of intelligent, humorous and subtle screenwriting, as well as the use of several Tarantino tropes.

Black suits, careless swearing and of course Samuel L. Jackson at the heart of it all, the scene ends in the murder of Jules’ target – Brett – after a long, seemingly extraneous conversation.

Despite fast-paced quips about burgers and beverages filling the scene, the importance lies in the subtext of the dialogue and context of the relationship between the characters; a technique Tarantino uses regularly, and arguably better than anybody else in the business. Incomparably cool, calm and collected, Jules indirectly threatens Brett throughout by being over-polite, asking constant questions, and even eating his breakfast.

Constantly ascending to an inevitable climax of gunfire and violence, the underlying tension of irrelevant dialogue develops into the true reasoning behind Jules’ visit, developing both the non-linear plot and character arc of Jules, one of the most loved members of Tarantino’s cinematic universe. Brilliantly written, effortlessly stylish and a regularly quoted staple of pop culture, if you’re looking for vintage Tarantino, look no further.

12. The Coen Brothers – Barton Fink (1991) – John Goodman in a fiery hallway with a shotgun

Despite making the occasional serious drama such as No Country for Old Men, Joel and Ethan Coen are primarily renowned for their dry and peculiar black comedies that present both the absurd and perceptive simultaneously.

1991’s Barton Fink, starring several of the Coen’s frequent collaborators, including John Turturro and John Goodman, follows Turturro’s Fink, a screenwriter in Hollywood.

Goodman plays an insurance salesman who lives on the same hallway as Fink, however, in a classic Coen’s plot, Goodman is exposed as a violent serial killer named Karl Mundt. After Mundt kills a police officer and sets the hallway on fire, he nonchalantly enters Fink’s room and remarks – “Brother, is it hot”.

Large amounts of violence are common in the brothers works, with murder and police officers also being recurring themes throughout their filmography. Witty and intelligent screenwriting that creates the humour in the scene follows, a key part of the Coen’s filmmaking and a technique they use in the vast majority of their works to create their unique black comedy style, which is seen throughout this scene towards the end of the Palme D’Or winning Barton Fink.

13. Ingmar Bergman – The Seventh Seal (1957) – Playing chess with death on the beach

After a harsh upbringing from a strict Lutheran father, it is no surprise that theology, religious faith and questions of existentialism are present throughout the Swedes filmography. The most famous (and obvious) example of this is 1957’s The Seventh Seal, starring Max von Sydow as Antonius Block; a disillusioned Knight returning from the Crusades that has begun to question the legitimacy of God, and existence itself.

Included in the Vatican’s list of 45 “Great Films”, the religious allegory begins with Block sitting on a beach with an anthropomorphic representation of Death (Bengt Ekerot), and curiously the two begin a game of chess – if Block wins, he gets to live, however if Death triumphs then Block has to accept the inevitable state of death without compromise.

A seemingly trivial game to decide life or death upon, the scene presents a sense of light heartedness on a deeply complex and philosophical subject matter, which can be seen other early Bergman works such as Wild Strawberries (1957) and Through a Glass Darkly (1961).

Filmed in a starkly contrasting monochrome colour scheme, Bergman’s key themes and motifs of existentialism and religious integrity are explored effortlessly in this scene, whilst being simultaneously paired with striking visuals that prove his value as a cinematic artist of the mise en scene and a unique auteur.