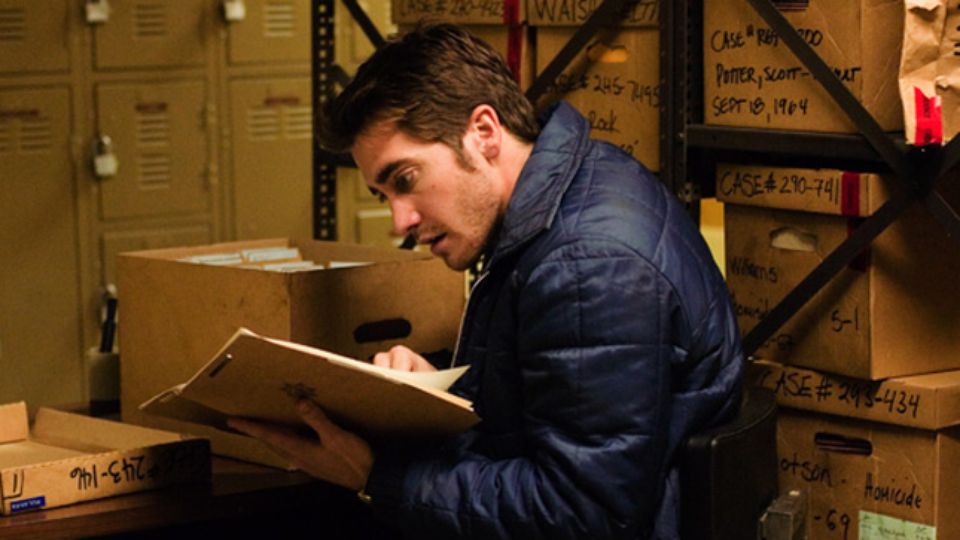

14. David Fincher – Zodiac (2007) – Graysmith trapped in the basement scene

Despite his diabolical debut with Alien 3 in 1992, David Fincher has since become a modern American auteur, with his contributions to the “thriller” genre in particular garnering him critical acclaim with films such as Se7en, Fight Club, and Zodiac, based on the true story of the Zodiac serial killer.

Fincher’s cinematography, as well as his dark and mature subject matter, is what separates his films from the rest of the occasionally unvaried 21st century thriller features, and this can be epitomised in the “basement scene” featuring Jake Gyllenhaal in Zodiac.

As a sweating Graysmith (Gyllenhaal) negotiates his away around a dingy cellar, Fincher arranges the mise en scene and lighting of the scene to perfectly match his personalised style. Supporting the dark narrative of the film, Fincher uses shadowy, ominous lighting in a glum and depraved looking set, emphasising the disdain the characters find themselves in and presenting the harshness of the cinematic world that he has created. This can be seen throughout his filmography, with darkness, shadows and drab set designs not only being used consistently in Se7en, but also in Fight Club and Panic Room.

Filmed entirely with a tripod and without hand held camerawork (Fincher rarely uses camera movement that isn’t completely stable), the scene even features a repeated Easter egg in Fincher’s works – a glum fridge solemnly placed behind the action of the narrative.

Perhaps not the most entertaining or memorable scene in the director’s inventory, however it does show a large amount of features from his directorial practice, and exemplifies why Fincher’s brooding thrillers stand out in Hollywood’s sea of typical and monotonous mystery dramas.

15. Ridley Scott – Blade Runner (1982) – Los Angeles 2019, flying over the city

Philip K. Dick’s “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” may have provided the complex thematic source material for Ridley Scott’s legendary neo-noir science fiction thriller Blade Runner, however it is clear that throughout the feature that Scott impresses his own cinematic expertise on the film, mainly through the use of visual and design effects – one of his strongest directorial facets.

Despite the film’s release preceding the invention of digital technology such as CGI, the use of models, paintings and clever camera tricks resulted in a fantastic and realistically designed world (Los Angeles 2019) that completely contains the narrative and tone of the film with its dark, smoggy and dystopian atmosphere.

Scott is renowned for his ability to create cinematic landscapes through the use of set design and special effects, with the Nostromo in Alien and the “Hab” base in The Martian both being acclaimed and popular examples.

As the camera glides over L.A and we see flying cars and explosions fill the sky, Scott’s creation instantly comes to life and allows the narrative to reveal itself without obstruction, proving his value as a visual artist and a master of film design.

16. Federico Fellini – 8 ½ (1963) – Opening 3 minute dream sequence

After a period of harsh socio-documentary styled Italian Neorealist dramas, Federico Fellini changed the face of both his own and Italian cinema, creating works of aesthetic brilliance with recurring motifs of dreams, memory and fantasy that excited cinema with an extravagant and unique view of society.

Of all of his superb works, 8 ½ stands above the rest as a baroque masterpiece, and the opening 3 minute dream sequence in which Anselmi (Marcello Mastroiani) epitomises the circus-like cinematic world of Fellini, and the idiosyncratic directorial style he made his own.

Shot in highly contrasting monochrome like many of Fellini’s strongest works, the scene shows Anselmi stuck in a huge traffic jam, only to seemingly escape by flight until he is literally pulled back down to earth with a piece of rope around his ankle; not dissimilar to a circus balloon.

A point of view shot from Anselmi in the sky, looking down upon his foot being pulled downwards is quintessential of Fellini, beautifully absurd and creative, whilst also being highly personal to the director’s own directorial problems.

A semi-autobiographical work, the struggles and Fellini and his character are expressed throughout this dream sequence, using the traffic jam as a representation for creative endeavours, and the escape into the sky as an innovative breakthrough. The whole sequence (and film, in fact) is avant-garde, extraordinary and completely individual – Fellinesque.

17. Yasujiro Ozu – Late Spring (1949) – Dinner sequence

One of the first great Japanese filmmakers, Yasujiro Ozu’s placid yet striking set of filmmaking conventions subverted those of commercial Hollywood, and, in his post-war films especially, offered a serene alternative to the occasionally acerbic melodramas of the 1940s and 50s. His signature “Tatami” shot – placing the camera in a low position, only one or two feet of the ground – can be seen multiple times in the “Dinner sequence” in Late Spring, arguably Ozu’s best film of the 1940s.

This abstinence from traditional eye-line level shooting creates a calm, composed effect on the viewer, and is a key technique used consistently throughout Ozu’s career.

In addition, his dismissal of the classic “over the shoulder shot”, in favour of a camera position that faces a single character directly during a conversation, again subverts traditional techniques at the time, and simultaneously makes the audience feel like they are literally in the middle of the conversation between the two participants – exemplified in the conversation between Noriko and Shukichi.

Themes of marriage and family are central to Ozu’s filmography; shown again in the dinner scene, as the duo converse about whether or not Noriko, Shukichi’s daughter, will marry – Shukichi is played by Chishu Ryu, a regular participant in Ozu’s films.

Quite unlike any other filmmaker then or since, Ozu’s set of cinematic norms are heavily contrasting to the commercial world and create a feeling of serenity and calmness, encapsulated subtly in the short three minute dinner sequence in his 1949 effort.

18. Sergio Leone – Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) – Opening, waiting for the train scene

The godfather and creator of the “Spaghetti Western”, Sergio Leone’s filmmaking style is one of the most unique in cinema. He would commonly use close up shots that show intense emotion and purpose juxtaposed with extreme long shots that created a peculiar sense of distance; the long shots isolate the characters in the deserts of the west, seperating them from reality, whilst the close ups heavily focus the audience upon these characters, adding empathy to their purpose and motives in the narrative of the film.

This can be clearly be seen in the opening sequence from Leone’s magnum opus, Once Upon a Time in the West. Whilst Jack Elam and Woody Strode wait in near silence for Charles Bronson’s “Harmonica” to arrive at an empty train station, Leone creates tension by using little dialogue and a creaking, minimal soundtrack that emphasises the desolation of the setting.

When paired with the unique contrasting of long takes and extreme close ups, the scene exemplifies a film form that moulded “Spaghetti Western” cinema and presents the embodiment of an atypical cinematic ideology that has been unrivalled in the Western genre then or since.

19. Krzysztof Kieslowski – A Short Film About Killing (1988) – Jacek’s execution

With the highly ambitious Dekalog, Krzysztof Kieslowski not only received large critical acclaim and an improved reputation in the realm of European cinema, but also had a strong basis for two more feature length films, one of them being the brutal and evoking Polish drama A Short Film about Killing. Jacek, a lost youth in Warsaw begins to indulge in minor violence and disturbances, which eventually escalates into the graphic murder of an innocent taxi driver, and a death-sentence penalty for the perpetrator.

The scene depicting his execution, strikingly directed by Kieslowski, creates a disturbingly realistic representation of a hanging, with Jacek seemingly asking for forgiveness and asking to be buried next to his father and sister, adding a personal emphasis to the scene and making it all the more evocative.

As with the majority of Kieslowski’s films and sequences, he purposefully uses very little dialogue and exposition, instead creating drama through the images on screen, helping the audience feel for themselves what is happening rather than being told by the director.

In raw, dingy and grimy surroundings, Jacek dies with nobody around him and no sympathy for him – not from Kieslowski either – which brings a simple but emotionally effective piece to a startling conclusion, and exemplifies the bleak, realistic and non-verbal philosophical filmmaking of the greatest Polish director of the 20th century.

20. Darren Aronofsky – Requiem for a Dream (2000) – Sara’s (first) psychotic episode

A combination of controversial subject matter and a surrealist, graphic style makes Darren Aronofsky one of the most recognisable and acclaimed filmmakers of the digital age, with Black Swan and The Wrestler being nominated for Oscars in multiple categories.

However, it is his second (and arguably his best) feature, Requiem for a Dream, that encapsulates Aronofsky’s unique film form. He depicts 4 drug addicts, each with varying dreams, vices and downfalls – none of which are more shocking and harrowing than Ellen Burstyn’s Sara Goldfarb, who, after becoming addicted to weight loss amphetamines, psychologically collapses through a sequence of hallucinations in her front room. A bizarre series of images are shown, implying the characters complete mental breakdown in a visual form – similar scenes can be found in Pi and Black Swan, and have become an Aronofsky speciality.

As Sara’s own hallucinations humiliate her, laughing at the state of her apartment, an inanimate fridge comes to life and charges towards her until she can no longer take the mental torment, screaming and running out of her own apartment into the corridor.

An empty, near silent room is then revealed in comparison to the deluded mind of Mrs. Goldfarb, emphasising the surrealism of the scene and the mental decline of the character, which is used as a major thematic link in Requiem for a Dream and the majority of Aronofsky’s films.

Author Bio: Will Jones is a student from Manchester, balancing time between school work, film writing and visits to the cinema. Interested in filmmaking and literature whilst also vying for a career in the film industry, you can find Will on Instagram @willl_jones.