14. Go Down Death (Aaron Schimberg, 2013) / USA

“A womb don’t rhyme with tomb for nothing.”

Not the best film on the list, but definitely amongst the top five when it comes to full-fledged weirdness and originality, “Go Down Death” is an experimental, phantasmagoric dramedy set in a godforsaken village whose inhabitants appear as ghosts of the Wild West past.

A gravedigger boy (who writes dark poetry) is threatened by a shape-shifting doctor. In a seedy, smoky tavern, a disfigured gambler yearns for a Japanese cabaret singer who’s completely tone deaf. One of the prostitutes from a ramshackle brothel looses her eyesight, hearing and voice, right before the intercourse with a war hero. And so on, and so forth.

Composed of several wry, colliding and intertwining “stories” based on the writings of the fictitious folklorist Jonathan Mallory Sinus, Schimberg’s one and only feature-length offering is painted with hushed melancholy and seriously distorted humor. It’s hard to tell what exactly is (about), though. According to the title, it could be a tongue-in-cheek ode to death.

Drawing comparisons to the works of Guy Maddin, David Lynch, F.J. Ossang or even Edgar Pêra, this piece of surreal or dada Americana is like a potpourri of some cowboy’s fragmented dreams and recollections. Featuring excellent set and costume design, gorgeous B&W cinematography, sudden cuts and blackouts, stupefying dialogue and soliloquies, as well as the brooding soundscapes of wind blowing and organ playing, it lulls you into a state of dizzying hypnosis.

(And not to mention that out-of-nowhere “twist” of its last quarter…)

15. Lucifer (Gust Van den Berghe, 2014) / Mexico | Belgium

At IMDb page, there are interesting bits of trivia about the circular format which the young Belgian director Gust Van den Berghe utilizes for the last installment in his “triptych about the emergence of human consciousness”.

Shot in so-called Tondoscope (inspired by the Renaissance paintings and supposed to mimic enclosed paradise with Heaven at its center), it features several innovative scenes with 360° panoramic view, while the rest of the film just happens to be composed of frames which have a spying-through-periscope feel to them.

This “obfuscation” takes a while to get used to and occasionally, it is not quite justified, yet it is intriguing rather than bothersome, whereas the soft focus that reduces the saturation of colors is in complete accordance with the religious themes and methodical, non-judgmental storytelling.

The action takes place in a Mexican village near the volcano of Parícutin where time seems to stand still and people hold on to tradition and superstition. It is a perfect playground for cunning Lucifer on his descent to Hell. He comes upon an elderly woman, Lupita, and her granddaughter Maria, and decides to put on a Good Samaritan mask and save the girl’s lamb. Back at their home, he “heals” Lupita’s no good “paralyzed” brother and seduces Maria, taking off suddenly…

Following his departure is the villagers’ (all played by the local non-pros) awakening of sorts tinged with moments of magic realism. Van den Berghe does not moralize and neither does he goes too far in subversion of the Christian mythos, portraying the human characters from the anthropologist’s perspective and Lucifer (Gabino Rodríguez , excellent) as an entity of wisdom.

16. They Call Me Jeeg Robot (Gabriele Mainetti, 2015) / Italy

With his directorial debut, the Italian actor Gabriele Mainetti brings a gritty combo of social satire and superhero tropes in a package that is far removed from the gloss of a Hollywood production. It stars the sad-eyed Claudio Santamaria as a small time crook addicted to porn and vanilla pudding who falls into a barrel with hazardous waste, while trying to escape the forces of order.

No, he does not transform or rather, deform into a Toxic Avenger, but he does vomit badly prior to getting a fair share of superpowers. However, it’s not until he ends up babysitting his neighbor’s autistic adult daughter Alessia (a great first-time performance by Ilenia Pastorelli) that he becomes aware of his newly acquired abilities.

The girl triggers his moral metamorphosis and crushes the emotional walls surrounding him, all the while convinced that he is Hiroshi Shiba – the hero of “Steel Jeeg” anime series based on Go Nagai’s manga.

The unlikely duo takes us on a wild ride through Rome’s ugly underbelly, almost naturalistically depicted and inhabited by sexually ambiguous mobsters, such as the Joker-level psychopath Fabio ‘Zingaro’ (lit. Gipsy) Cannizzaro portrayed by the scene-stealer Luca Marinelli.

Mainetti’s down-to-earth approach doesn’t require our suspension of disbelief to be stretched too much, despite the quirky flourishes and the “sci-fi” bits. Even when hyperbolized, his characters feel credible, making the drama genuine and the violence impactful. Topping that are his skills in juggling tonal shifts and the score’s unobtrusiveness or total absence which enhance the realism of flickering images.

17. Sisyphus K. (Filip Gajić, 2015) / Serbia

“We are asking Death to respond by calling a number 0900-0905-945.”

The reason no one talks about the stage director Filip Gajić’s debut feature is as simple as a limited distribution, as well as the unavailability of (English) subtitles for the official YouTube release. And it’s really as shame, given that “Sisyphus K. (Sizif K.)” feels like a breath of fresh air in the Serbian cinema.

Deconstructed and peppered with Kafkaesque absurd (as the very title suggests), the myth of Sisyphus is relocated from Ancient Greece to alternative modern Serbia and intertwined with the autobiographical docu-drama about Gajić himself who wants to transpose the said myth to the silver screen.

Therefore, we follow two narrative threads – a (meta?) story of creative obsession and long-distance marriage, and the shepherd Sisyphus Kadmovski’s “divine mystery” which involves the kidnapping of Thanatos and inducing chaos. For the second one, Gajić applies the “formula” which is similar to Christophe Honoré’s “Metamorphoses”, given that immortals don’t differ from humans.

Everyone dresses a little bit eccentrically, so we have Zeus parading as a marshal in white overcoat (Tito reference?), whereby the members of his secret police look like some 40s noir detectives. An abandoned factory serves as Mount Olympus, and the monumental Avala mausoleum is utilized as the Thunderer’s throne.

On his quest for the answer(s) to the question(s) of death, Gajić equates life and the process of creating art with a Sisyphean task, giving a social commentary through the radio news turned into a running gag. Although he shoots on a limited budget with the inexperienced Marina Perović behind the camera, he delivers plenty of attractive images in this whimsical and ambitious arthouse film.

18. Sleep Has Her House (Scott Barley, 2016) / UK

“Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing…”

(excerpt from Raven by Edgar Allan Poe)

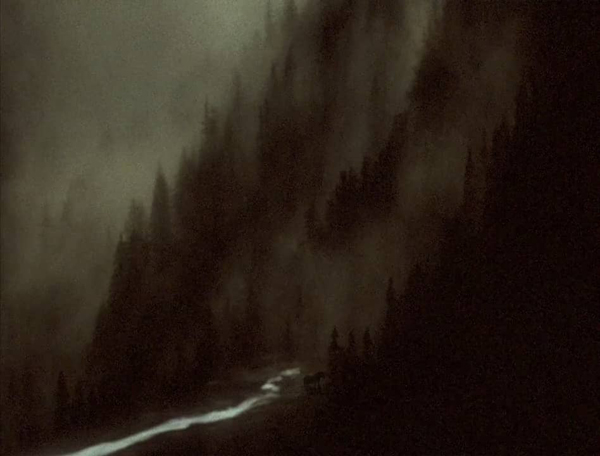

After the series of experimental, genre-and-boundary-defying short films, all intended to be seen in complete darkness and with headphones, the Welsh Born, London-based artist Scott Barley delivers a feature-length experience unlike any other. A logical continuation of his previous efforts, “Sleep Has Her House” is certainly the blackest film about Mother Nature – her soul, essence, silence and grim side.

Barley’s cinematic phantasm in which “the shadows of screams climb beyond the hills” is difficult to describe, but that doesn’t take away from its nocturnal beauty. There’s no conventional narrative or characters in his exploration of cloaked, tenebrous, impenetrable “otherness” and the very notion of those two aspects is obscured by the Moon’s timid rays, an owl’s piercing eyes, the stillness of roe’s corpse, the soaring thunder which announces the End and even by the small intrusions of light.

In the seamless blend of detailed artwork and long, static shots of a lake, river, waterfall, night sky and thick coniferous forest shrouded in fog, one can sense the presence of an unknown, concealed entity and find comfort in Its firm, maybe deadly embrace…

19. We Are the Flesh (Emiliano Rocha Minter, 2016) / Mexico | France

Emiliano Rocha Minter’s feature debut brings a revision of “Hansel and Gretel” as an odd, daring blend of psycho(patho)logical drama, artsy horror/mystery and straight-out hardcore porn set in a decrepit residential building, probably after a cataclismic event.

Initially, we are introduced to the (male) “witch” turned to a sleazy and sadistic Messianic figure who later welcomes a pair of starving siblings into his lair, under one condition – to follow his rules. The trio begins building a cavernous structure inside a large room where all of them will be reborn in the most uninhibited way possible. (Expect all kinds of atrocities, from a poisoning attempt, through incestuous sex and all the way to necrophillia and cannibalism.)

Subverting the idea of family, freedom and humanity, “We Are the Flesh” explores the darkest recesses of our minds through the maniacally poetic and painfully enlightening imagery – kudos to Manuela García for top-notch art direction and Yollótl Alvarado for his sultry cinematography. All the while, sparse dialogue of (deliberately?) chaotic screenplay is complemented by Esteban Aldrete’s suitably quirky score.

Minter follows in the footsteps of the world cinema’s les enfants terribles, such as Fernando Arrabal, delivering a biting, irreverent, transgressive, iconoclastic and, to a certain extent, esoteric existential satire of demonic energy. It’s memorable not only for its shocking contents, but for the strong central performance as well.

20. Still the Earth Moves (Pablo Chavarría Gutiérrez, 2017) / Mexico | Spain

“The earth still moves, under the torsion of the serpent.”

Similarly to Scott Barley, the graduate biologist turned filmmaker Pablo Chavarría Gutiérrez, defies the conventions of dramatic structure and creates a new, both universal and obscure cinematic language in the process.

A love-or-hate affair, his latest offering is the work of abstract art featuring dancing lights, a dead baby bird, people at a busy fair and a turtle laying eggs framed from the most unpleasant of angles, inter alia. Oft-blurred and rippled tableaux vivants drenched in the cacophony of sounds seem simultaneously poetic, elusive and meditative, even at their most banal.

There are no story and characters in the traditional sense, the pace is deliberate and words are rarely heard, because Gutiérrez favors evocative imagery over all other aspects. A (pseudo)mystery of metaphysical quality, “Still the Earth Moves (La tierra aún se mueve)” is reminiscent of a foggy, occasionally nightmarish dream replete with disorienting déjà vus and non-sequiturs.

It is “the neverending simulacrum” of what “just burns and can’t be said”; “the excess of life” as seen through the eyes of a supreme entity suffering from an unknown psychological disorder. And whatever the case of the author’s pushing the limits may be, the trippy, otherworldly experience he provides is of a rare kind these days.

Author Bio: Nikola Gocić is a graduate engineer of architecture, film blogger and underground comic artist from the city which the Romans called Naissus. He has a sweet tooth for Kon’s Paprika, while his favorite films include many Snow White adaptations, the most of Lynch’s oeuvre, and Oshii’s magnum opus Angel’s Egg.