The 1980s is perhaps one of the most defining decades of 20th century Britain. Not only had it rejigged the country’s political and economic ideologies (for better or for worse) but culturally, it was time of great creativity and diversity as a response to this changing landscape.

British cinema was especially changing, from a decline in the 1970s after American studios slowly stopped backing U.K productions and with less funding from the newly formed 1979 conservative government. A lot of filmmakers turned to television to be cinema’s saving grace.

From the launch of Channel 4 in 1982, independent productions as well as much larger ones began to receive funding which, in turn, allowed new and interesting films to be made, providing a distinct critique of the era. The Films on Four scheme helped fund figures who became defining (or in some cases, already defined) figures in the industry such as Peter Greenaway, Ken Loach, Sally Potter, Derek Jarman, Stephen Frears and Mike Leigh, to name but a few.

Of course these films were still available to watch on the silver screen, but the 1980s begged the question of what exactly was the true cinematic aesthetic in the face of more quality television being produced?One film that falls slap bang in the middle of this debate is the 1984 film Threads.

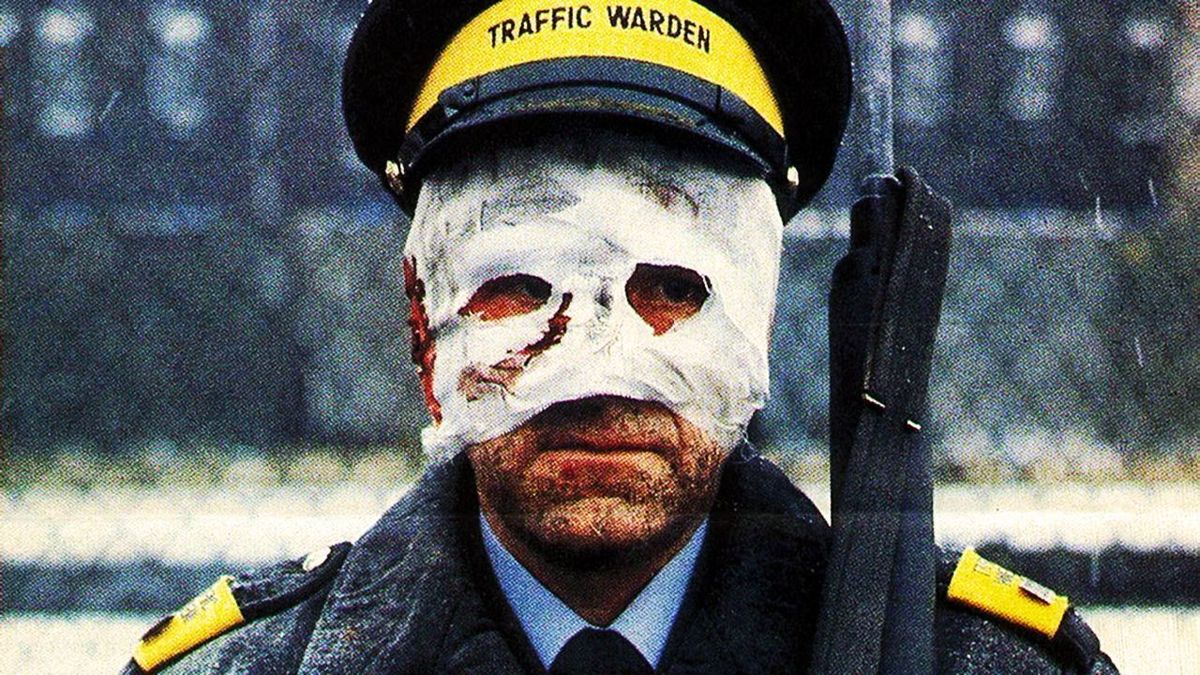

Threads is a made for TV film which was broadcast on the 24th of September by the BBC and was directed by Mick Jackson who would go onto to make the sublime television series A Very British Coup (1988) as well as the 1992 film The Bodyguard.

Set in, then, present day Sheffield the film depicts a nuclear bomb hitting the city after an outbreak of a major conflict due to Soviet and U.S aggressions in the middle-east. The film follows the lives of young couple Jimmy and Ruth who, with a baby on the way, try to settle down in the midst of these political tensions.

*SPOILERS* After the bomb destroys most of the city, killing Jimmy in the process, it is up to a heavily pregnant Ruth to try to survive in the nuclear wasteland. The situation only gets worse as food supplies diminish, population begins to dwindle from starvation and disease as well as a freezing nuclear winter, reverting Britain to the dark ages.

Eventually Ruth gives birth to Jane, the new generation to be born in the ashes of the old one. As we watch Jane grow up, we soon learn that society has completely crumbled with the loss of language, technology and any tangible human relationships. She becomes pregnant eventually giving birth in a makeshift hospital where film ends with her screaming at the unseen, but presumably terrifying, infant in her arms.

But what exactly makes this particularly bleak film so interesting and important to British cinema? Here are five reasons for your consideration:

*Just a quick note: This is neither a condemnation nor appraisal for any political party/ideology, this is written as an analysis for the film. I am trying to discuss what certain aspects could mean rather than what they do mean and how these fit into an aesthetic and historic context*

1. Awakening Anxieties

Threads is certainly reflective of the 1980s fear of a nuclear war in the midst of Cold War tensions. But perhaps the film wouldn’t have been made in quite the same way if it wasn’t for an earlier and equally as shocking film from another period.

In the mid-1960s, Young Turk filmmaker Peter Watkins made a short film for the BBC titled The War Game (1965) which depicted a nuclear bomb being dropped in UK and the consequent psychological implications that it would have upon the nation. The film is a landmark in British cinema and still proves shocking to this day for its uncompromising horror in showing the hysteria and madness of a nuclear attack.

Watkins blends fiction and reality in a documentary style, a genre which in itself was being innovated with the direct cinema and cinéma-vérité movements. This aesthetic had already been experimented within Watkin’s seminal 1964 film Culloden, the success of which allowed him to make the more ambitious follow up. Watkins spent the best part of a year researching for the film, reading hefty tomes on the subject as well as interviewing experts in the field.

In doing this, Watkins hoped, through the medium of mass entertainment, to give full coverage to a subject which was rarely discussed or even well known among the British public. However, the BBC never televised the film on the grounds that it was too shocking and would perhaps frighten young children and elderly people (yes, really), potentially creating a state of hysteria among viewers.

This was the ‘official’ story however there is evidence to suggest the real reasons and motivations were far more political. To this day many investigators and academics are still finding new information on how the film had intimidated the British establishment and the bureaucracy that came with the banning, but that is perhaps for another day.

For two decades The War Game was ‘officially’ unseen by many, until finally being televised in 1985 in a string of programmes which commemorated the anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings in 1945. However, by that point a lot people in Britain had seen The War Game illegally through secret screenings which were mostly co-ordinated by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). So it is highly possible, if not entirely possible that the creatives behind Threads had seen The War Game prior to making the film.

There is almost a redemptive quality to the BBC broadcasting and producing Threads which, for all intents and purposes, is a far more extreme piece than The War Game. The film is certainly more violent as well as emotionally destressing by giving a range of named characters whom of which the audience spends ample time with, only for them to end up dying in complete agony. However, the film’s aesthetic form is certainly reminiscent of The War Game, beginning with that same pseudo-documentary style before quickly mutating into a deeply disturbing drama.

Threads also excellently gives an insight into the tensions and opposing opinions when it comes to the nuclear deterrent. In the first act, there is a sequence where the CND give a rally to oppose the coming conflict, brandishing such slogans as ‘Jobs not Bombs’, it feels as if it is a genuine rally. The group are then met with some agitators feeling the deterrent is important to the nation’s defence with one voice even shouting ‘What about the Falklands?’ Whereas The War Game shows a more clueless nation, Threads represents a society which is becoming more in keeping with its social milieu.

2. A dangerous relationship

The UK/US special relationship has been detrimental to the Western politics of the 20th century as it soon became apparent that America was becoming one of the domineering powers of the world. After World War Two it seemed strategically important for a weakened Britain to latch onto its imperial protégé as its own status as an empire began to unravel.

This has since been an often fruitful agreement for both nations. Come the subsequent elections of Margaret Thatcher in 1979 and Ronald Reagan in 1981 with their own brand of right wing social policies and neo-liberal economics, the special relationship became very important. But to some, this relationship seemed dangerous and created anxieties as the US began to grow stronger and more influential.

Threads begins with an establishing shot above Sheffield, a distinctly English city but as we pull out we notice a Ford muscle car with Chuck Berry twanging over the radio, both of which seem a little anachronistic in a 1980s TV movie set in Sheffield. The scene is reminiscent of the iconographic cultural images of post-war 1950s America, one wouldn’t be surprised if the hill which the car is parked is called ‘make out point’ or something just as grisly.

The use of American iconography evokes a sense of cultural imperialism as the U.K under the conservatives aimed to be a more globalised economy, but in the process began to lose its own national identity. The haunting re-use of Chuck Berry in the final moments of the film does not only give an ironic mirroring to happier days but also reaffirms the U.S’ cultural dominance, even in a barely functioning society.

Jets scream over the city often silencing people’s conversations which serve as a constant reminder of the U.S instilled military bases all over the U.K. In the 1980s, the presence of these military bases were often met with resistance from the British people, especially as the U.S began to move dangerous weapons into them. The jets are shown as a disturbance to the characters in Threads but are often ignored giving a particular sense of the British people’s helplessness, despite knowing there is something not quite right they choose to ignore it.

When the British people do seem to finally take notice, it is too late and they pay the price for it. The films provokes the British people’s reluctance in challenging the U.K’s often ardent support of aggressive U.S foreign policy. This is represented in the film by a somewhat bellicose caricature of Reagan, who seems to be the first that alludes to a nuclear war.