How do you explain the truth when it has been said for you? The best films, let alone animated ones, seem to take the words right out of your mouth. You feel as if a filmmaker has miraculously bridged their past present to your future present, all to make you feel more understood and a little less insane.

Great animated films, from Fantasia to Pixar’s finest to wondrous contemporary gems like Don Hertzfeldt’s It’s Such a Beautiful Day, all have played with a world that only exists onscreen. Richard Linklater, perhaps the quintessential independent American filmmaker of his era, has often crafted fables that exist in reality.

With Waking Life, one of his only two animated films, he conjoined the tangible and the elusive with a film that blurs the line between the surreal and the substantial. In a genuinely grandiose and poignantly lo-fi cinematic feast for the eyes and the brain, he molded what could be considered the most profound animated film of all time. Here are five reasons why Waking Life deserves such stature.

1. Revolutionary animation

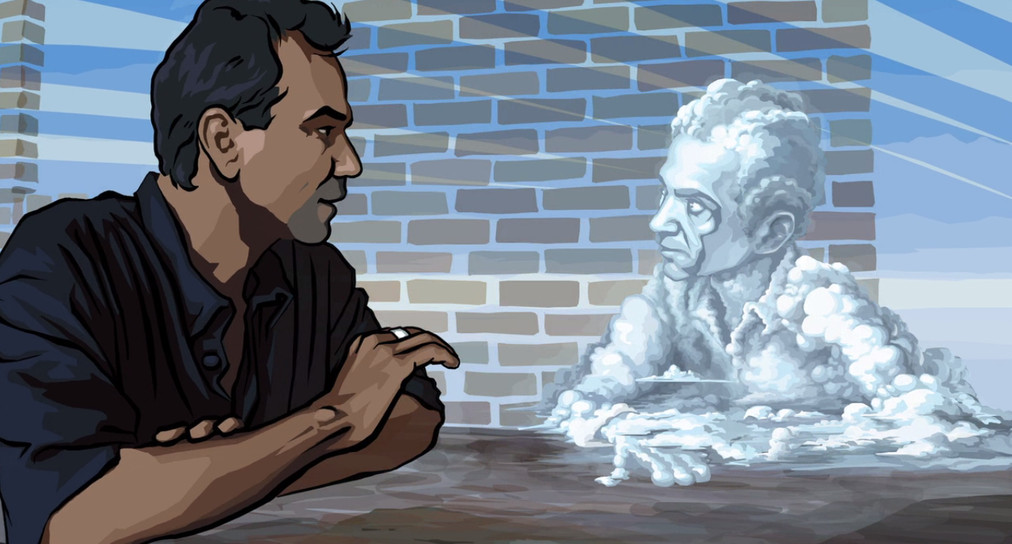

On a strictly visual level, Waking Life was groundbreaking and remains to this day unmatched as a work of animation. Utilizing a breakthrough in computerized rotoscoping, rather embarrassing digital camera footage was purified into a film of evocative fluidity. Combining several styles of animation from scene to scene into a seamless whole, vivid colors and wavering, double-vision-esque and undeniably psychedelic imagery form the vibrant backbone of a picture with so much more to offer outside of its intoxicating visuals.

Five years after Waking Life’s release, Linklater’s own adaptation of the near-future novel A Scanner Darkly by Philip K. Dick – who clearly holds a particular appeal for Linklater, as Dick is integral to the epilogue of Waking Life – would become another obvious outlet for the use of rotoscoping’s unique visual effect. A Scanner Darkly is a minor masterpiece in its own right, and rotoscoping is perfect as a way of communicating the mind-altering effects of the film’s central addictive drug, Substance D, but not for much else apart from that.

In Waking Life, rotoscoping has an enormous role to play: it communicates the slipperiness and volatility of dreams while simultaneously drawing our attention to their uncanny yet utterly familiar relation to real life. It also offers opportunities for the film’s many monologues to be enhanced with flourishes that visualize the topics they explain.

Numerous solo speeches are enriched with these playful touches, the most memorable of which being David Sosa’s explanation of our place in relation to the physical laws of the universe and quantum mechanics as well as Kim Krazan – writer alongside Linklater on his marvelously romantic and comparably perceptive Before trilogy – trying to verbalize the limitations of words as we come to define the abstract, or that which is “unspeakable.”

2. Flawless dialogue

It’s one thing to find the right words to do any kind of justice to life’s many ineffable qualities, but it’s an awe-inspiring feat to sum up the essence of existence in a series of interactions spanning just over 90 minutes.

One thing that is easiest to appreciate about Richard Linklater’s brand of filmmaking is that he stretches not just what you can accomplish with the film form, but with scripts themselves. He reaches for ideas that navigate an overarching meaning in the process of scene after scene of rich dialogue, and in Waking Life, the fragments seem unrelated before you see them altogether.

The 2001 film in some respects is a far more modern and perfected version of his early 1991 film Slacker, which similarly caught so many perspectives by letting the camera follow situations from stranger to passerby and so on. As Slacker begins with a character played by Linklater describing a vantage on dreams to a cab driver after a flight, Waking Life inversely ends with an appearance from the director further discussing the nature of dreaming.

Moreover, the film excels at feeling so real amongst such forcefully imposed surrealism due to the naturalism in each and every delivery of Linklater’s lines, something that he appears to encourage throughout his filmography.

Starkly contrasting every effervescent frame, the writing comes forth so purposefully due to the casual, conversational beats that each actor brings Linklater’s cinema vérité, near-docufiction format. To the ears, every monologue feels formed in a vacuum, where each philosophical musing is tailored to the deliverer, and bold, complicated ideas and revelations are conveyed with incredible clarity through intimate, genuine performances.

3. Thematic ambitions

“There’s no story. It’s just … people, gestures, moments, bits of rapture, fleeting emotions. In short, the greatest stories ever told,” says Alex Nixon – who under layers of flowing animation resembles a young Tarantino – when asked to describe a novel he is penning.

Amongst so much pontificating about our place in the cosmos and the state of the human condition as it stands just at the turn of the millennia, Waking Life also highlights Linklater’s own struggle to say something forward and honest about the creative process and filmmaking itself. Miraculously he pulls this off without feeling strained or self-congratulating.

Louis Mackey, who appeared in Slacker, questions what causes so few of us to reach the heights of great figures in history by posing a devastating question: “What is the most universal human characteristic: fear or laziness?” Mackey’s lines identifies the agonizingly slow grind of human achievement, and Nixon too points to Linklater’s own processes of honorably reflecting everyday reality in his own work.

But perhaps as on the nose as Linklater gets on the subject is in one of the most unique moments in the film, and one easy to overlook. A chimp professor, voiced by Steve Fitch who is animated as such, conducts a brief seminar on modern culture as viewed from the future, with footage of punk rock concerts and bleak drama films as reference.

“Art was not the goal but the occasion and the method for locating our specific rhythm and buried possibilities of our time. The discovery of a true communication was what it was about, or at least the quest for such a communication.” Like so much of Waking Life, the consequences of Linklater’s rigidly self-aware intentions are most often resonant to absorb.

In perhaps the most self-reflexive and most cinematically profound segment of the film, our nameless protagonist finds himself in a movie theater watching Caveh Zahedi describe to David Jewell just what film truly seeks to capture. Reexamining parts of Andre Bazin’s celebrated film theory, he equates cinema to a record of God, one that is constantly changing. This sequence also discusses what Linklater calls The Holy Moment, where film can show that the present itself is yearning to be recognized within the specificity of its replicated reality.

Film’s duty is to show us this even though it’s practically impossible to exist within a heightened awareness at all times. This small scene is but a microcosm of Linklater’s larger goals throughout Waking Life, which is to succinctly explicate that life is raging all around us every second of every day. His ideology in relation to his films is to shake the viewer out of their passivity and into the ideal of really living.

This brings me to a fundamental thematic aspect to Waking Life, which is its unflinching optimism. From the onset, one of our first real monologues is driven by philosophy professor Robert C. Solomon’s who urges his students, and later Wiggins’ character in private, to look at existentialism without any sense of gloom, and thereby to simply take life positively as we conduct the story of our lives.

Aside from several bits with a much darker edge to them, the scope of Linklater’s observation and insight is one of unyielding exuberance, and he makes enthusiasm look downright courageous – especially considering the very loose plot deals with the acceptance of death by its conclusion. Released just weeks after 9/11, one can imagine how invigorating the film’s barefaced revel in contemporary life’s problems and potential must have been for the newly shaken and confused.

Instead of being circular and self-defeating, Linklater, in these scenes mentioned and anywhere else in Waking Life, sincerely gets at the heart of how filmmaking is supposed to move us, and how the abstract and the forthright can be communicated at once without pretentiousness or generalization.

4. Experimental narrative

It’s easy enough to explain the general premise of Waking Life – our protagonist, played by Wiley Wiggins in his only real starring role outside of Linklater’s cult favorite Dazed and Confused, is caught in an endless dream state that ultimately suggests this is his remaining brain activity immediately following death. Richard Linklater’s invariably dense script, however, leaves room for countless narrative detours that sometimes don’t enhance the film’s plot – what little plot there is – but further molds the complexity and range of the philosophical standpoints that he employs.

Some parts of the films, like Charles Gunning’s brooding, venomous prison confession and the early orchestral band rehearsal, have nothing to do with Wiley Wiggins’ character or his psychoactive story.

Even in vignettes where he is present, the point is that he is the audience to any given speaker, and their views may not have much to do with his own concerns. But no matter how little each persona’s ideological stance seems to relate to Linklater’s own storytelling goals, each piece feels essential to the intricate puzzle. Each piece can be taken on its own, and yet even the shortest oration is an indispensible link in a chain of subconsciously stimulating thought.

Interludes with channel surfing – which features Kregg A. Foote briefly engaging in ego-breaking discourse as well as Mary McBay explaining the dream-state of death our protagonist finds himself in – offer key ideas and a break from the expansive soliloquies. Linklater steadily oscillates between broadening the mind and enhancing the nuances of his tricky tale.

And a sketch as good as the post-coital ramblings between Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke function as an interesting missing piece to the Before trilogy while nonchalantly clarifying to the viewer about the 6-12 minutes of brain activity that comes with death, before it actually becomes important to us.

The story of Waking Life is in many ways bare, though, viewed in a more discriminating state, the subconscious, intuitive way in which the film dissects both modern philosophical quandaries and the bizarre, beguiling phenomenon of dreaming is too remarkable to overlook.

Linklater’s earnest, ravishingly thought-provoking dialogue exercised effortlessly by various acting talents carries the film through its own hurdles in film structure – in few film’s is the dialogue more contingent to its internal propulsion. Waking Life seamlessly marries the avant-garde with the all too real, just as any film that wishes to merge the sensations of both living and dreaming on a visual and narrative level should.

5. Bridging the gap between director and audience

Breaking the fourth wall – from Pierrot le Fou to Annie Hall to Deadpool – has its place in the highest and lowest practices of film. Many directors choose to reroute the communication of their innermost feelings and sociopolitical opinions through exquisitely arranged discourse – at least some the best writer-directors do.

Before and after Waking Life, Linklater so often has used his films as a way to express himself as deeply as the medium will allow him, and its clear that his most fervent urgency, and his biggest soap box, lies in Waking Life. The film acts as a vessel for him to challenge the notion of a constant worldview or a singular perspective as he reaches into every corner of his soul in order to attain a higher state of objectivity and the widest array of truth possible in relation to life.

One of the deepest pleasures of revisiting Waking Life is in thinking about the certainty of the various characters’ attitudes and beliefs. Many align in reassurance while some clash with shades of morbidity. Each time you watch it, one speech that you always blew off as a pretentious flub may resonate more fully, like perhaps the extremist political stances touted by Alex Jones and J. C. Shakespeare. And something that seemed utterly profound might eventually appear more customary and blend back into the fabric of lyrically concentrated wisdom that the film already has in spades.

It’s not much of a challenge for a director to profess himself cinematically – especially in a movie as candid as this – but it’s really something to express as much as Linklater does without making your filmmaking efforts look pompous or overambitious in the process.

As the film reaches its end and Wiggins’ character begins to understand his fate, Linklater literally strips the veil separating artist from audience. Hunched over a pinball machine – a curious staple of many of his films – Linklater spins tales of Philip K. Dick’s paranoia and the filmmaker’s own twisted dreams, all to land at a place he often lands in his movies. He essentially pleads anyone watching not to give in to the commonplace distraction that comprises so much of film and culture, and offers a subdued and significant wake up call to our most bewildering present.

The final sentiment of Boyhood, Linklater’s biggest critical success, finds fresh college kid Mason reaching a related revelation while sharing a lovely conversation with a girl about the moment seizing us and how it’s always right now, all while soaking in some hallucinogenic chocolate.

Very similar thoughts are echoed in his Before films, recently in Everybody Wants Some!! and even Me and Orson Welles – all of his movies, at least in some small way, are related to time. In the subconscious infinity of dream-space, Waking Life’s parting sentiment is the same only moreso, and it finds a great director at his most direct: “There’s only one moment, and it’s now, and it’s eternity.”

It’s happening as I write this and as you read it. As long as Linklater is making movies, he’ll never stop trying to show us how dearly important it is that we understand that we are alive right now. So many animated films attempt to show you a world of escapist splendor impossible in the real world. The reality – or surreality if you will – of Waking Life is a place just as fascinating to inhabit, only the realm it forces you to look at in wide-eyed wonderment is already all around you.