Surrealist Luis Buñuel once stated, “Film seems to be the involuntary imitation of the dream.” This of course is of particular interest when it comes to Leos Carax’s 2012 French-German film Holy Motors, in which the French film director uses a metaphysical dreamscape to channel life as it is experienced while deliberately calling attention to the film’s construct of itself as a film rather than reality.

Despite not being a self-reclaimed surreal film, Holy Motors’ merger of both dream and cinema as well as its malleability in interpretation elevates the enigmatic film to the highest of Surrealism’s concepts.

Set in Paris, Holy Motors follows a middle-aged man named Oscar (Denis Lavant) in what is ostensibly a usual day at his job as he carries out a number of unusual, bizarre and seemingly meaningless “appointments.” Riding a stretch limousine driven by his associate Céline (Édith Scob), Oscar has the costumes, cosmetics and necessary supplies to fashion himself for the preassigned role of each appointment, from family man to manic psychopath. As the drama unfolds, questions about Oscar’s motives, the purpose of his employment, digital media’s influence as well as the boundaries of reality begins to arise.

Ambiguous. Absurd. Allegorical and melodramatic, yet deeply affectionate, Holy Motors is not only reminiscent of the works of the mid 20th century surrealists Cocteau, Wojciech Has and Dulac, but adapts the style while pushing the limits of what is technologically possible as well as expressing social concerns of today’s Digital Age.

Overflowing through surrealist work, this style and motifs include: juxtapositions between the quotidian and the fantastic, the shocking and thought provoking imagery, the dismantlement of conventional structure and institutions, and the neo-romantic pursuits of irrational passion.

Given that surreal has become an umbrella term throughout the years, it is necessary to point out that this discussion does not aim to place Holy Motors inside the confines of a surrealist film genre, whose legitimacy is still contentious for some, but from a modern approach, survey “Motors” according to the traditions of the 1920s cultural movement, its key characteristics, and its purpose.

According to the founder André Breton, this was to “resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality.” Up next are 6 aspects that make Holy Motors a worthy candidate to be called the most surreal film of the 21st century so far. Enjoy.

1. The Episodic Structure as the Innovative Form to Portray Life as Experienced

As Salvador Dalí puts it, “Surrealism is destructive, but it destroys only what it considers to be shackles limiting our vision.” Holy Motors’ structure is comprised of nine sequences (ten counting the interlude). Oscar’s “appointments” are ordered episodically and with the exception of their leading performer, they share no direct relationship with one another.

By extension, Carax rejects traditional narrative – the three-act structure, turning point, its accompanying momentum, moral standpoints – are but some of the conventional elements Holy Motors cast aside in order to become unpredictable, puzzling and anything but didactic.

More specifically, the use of both the episodic structure and independent sequences to narrate a 24 hour period of a man’s daily life stand as a synecdoche not only of cinema’s evolution (more on that later), but also of life as experienced.

Whether it’d be the role as father and family man, the musings about the past after reuniting with an old flame, or an individual’s last moments on a death bed, these allegorical vignettes capture life’s highs and lows by finding balance between the monotony of daily routine and the immediacy of lifetime’s most pivotal moments.

Similar to the stretch limousine that bridges these seemingly disjointed sequences and whose vehicular enclosure provides a barrier between Oscar the man and Oscar the performer, Carax indulges viewers to question the “appointments” and reach their own conclusions regarding their context.

For instance, the accordion interlude sequence featuring Oscar alongside a group of musicians breaking the “fourth wall” while performing a musical number calls attention to the nature of these episodes: are the “appointments” real or are they allegorical devices? Are they occurring at the same time and Oscar merely “slips” into them? Does it try to emulate reality or is it a movie about movies?

2. An Absurd, Enigmatic and Multifaceted Subject

In one of the streets of Paris’ nightscape, a stressed Céline rushes towards a commotion on the sidewalk just outdoors of a restaurant. “Excuse me, let me through please,” she exclaims as she pushes her way through the awe-struck civilians surrounding a blood soaked motionless body, it is Oscar.

Several bodyguards shot him after he assaulted and murdered their client, a banker that looked identical to Oscar. Céline kneels beside him and whispers to his ear, “Mr. Oscar. Come on, we’ll be late.” Slowly, Oscar gets up and carries on towards his next appointment.

If absurdity is the type of humor that violates logic, founded in the subversion of the beholder’s expectations, then it is the definitive term that describes not only Surrealism, but also Holy Motors’ chameleonic and enigmatic central character.

Whether it’d be a beggar, a father, a balaclava wearing anarchist, a flower and dollar bill eating manic leprechaun or a motion capture actor erotically simulating sexual intercourse, Oscar’s roles are as diverse and deranged as they are negligent of rationale. However, Oscar’s multi-embodiments only offer glimpses and impressions of the cryptic individual lying underneath, or as observed, if he is a real individual in literal terms.

Is it as simple as Oscar’s identity being separate from his body and appearance, an independent sentient consciousness manifested through different bodies? Or is “Oscar” a cryptic design whose purpose is to defy reason in order to incite reflection and convey truths? The professional shape-shifter never reveals.

Nonetheless, if there is something certain about the enigmatic performer is that he is a necessary contradiction, whose personas underline the possibilities for cinema as well as for an inborn infant. Melancholy, nostalgia, nurture, madness, confusion, and hope are all sentiments that Oscar emulates at different intervals, but hesitates to claim permanently.

3. Psychological and Thought Provoking Imagery

Surrealism nullifies the boundaries of reality in order to materialize the latter’s strangeness. Surrealist imagery is known for their visual subversion of reality, the longing impressions it casts on the psyche, and both complex and compelling commentary about inner, repressed desires.

More colloquial than Cocteau’s classicism and voyeurism, and on the fence between Švankmajer’s dark undercurrents and Wojciech Has’ literary fantasia, Holy Motors’ imagery is romantic, kinesthetic, and kaleidoscopic while clinging to utter darkness. Similar to the aforementioned filmmakers’ works, “Motors” offers visuals that are puzzling, rousing and malleable in interpretation.

For instance, the opening scene features “The Sleeper” (Carax himself) waking up to discover a hidden door on the forest themed wall of his apartment (a nod to Cocteau’s The Blood of the Poet). Suddenly, holding a key grown from his middle finger, “The Sleeper” unlocks the door to find a cinema. The audience is inert, hypnotized by the flickering screen while a naked child and a large, gloomy, and elderly dog stroll down the theater’s walkway.

As one might come to expect, the are many interpretations: some hold the theater scenery as the backdrop for the events and/or the “dream” to follow, or expounded the somber audience to be a representation of today’s mainstream audiences, or held the child and the dog as the birth and uncertain future of cinema, the new and the old. The possibilities are as many as the material’s contextual ambiguity allows it to be.

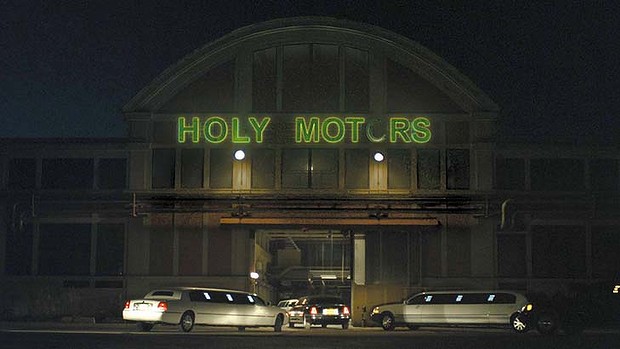

Other iconic scenes that use juxtapositions of irrational forms to isolate and reimagine particularities of the human condition include: Oscar – the “family man” – being received at his house by a family of chimpanzees, Oscar and Jean (Kylie Minogue) walking through a cemetery of broken mannequins at the Samaritaine building, the stretch limousines bickering to each other at the eponymous garage, and the motion capture simulated sex scene.

By far the most experimental in the film due to its technical innovation (great contribution by cinematographer Caroline Champetier), this last scene uses phosphorescent balls, black lights, and vibrant green screens for a scintillating effect and deliver both an otherworldly visual feast as well as social commentary, which leads to the next point…