4. Both films feature a hyper-masculine, obsessive protagonist who is forced to drastically alter his worldview

Man gets obsessed. Man’s obsession causes heartbreak. Man realizes he shouldn’t be so obsessive. Man lets go of his obsession. Man lives happily ever after, kind of.

If that narrative sounds familiar, it’s because it’s a favorite of many deep-thinking, tough-guy directors, including Scott, Aronofsky, and Christopher Nolan. When it comes to creating memorable male characters, all three may be too smart to excessively indulge in chest-pounding theatrics, but they also like to have their testosterone-spiked cake and eat it too, mainly by spotlighting macho protagonists who soften as they ruggedly trek toward their film’s end credits.

This well-worn tale often feels like an excuse to celebrate the tiresome spectacle of men raging, suffering, and fighting to showcase their manliness (with a weepy coda tacked on to hastily remind audiences that yes, boys have feelings too). That said, it’s a narrative that Scott and Aronofsky handled sensitively (thanks in no small part to the unabashed vulnerability of both Ford and Jackman’s performances).

The Deckard version of this story begins when he’s recruited by the smug policeman Bryant (M. Emmett Walsh) to hunt down and kill Batty and his cadre of replicants, who have illegally travelled to Earth (the film is essentially about immigration and, as a matter of fact, walls). It’s an assignment that Deckard doesn’t want, but he takes the job because Bryant tells him he has “no choice” (a grim punishment for disobedience is implied, but not clarified). Killing is worth it, Deckard seems to reason, if it insures his survival.

This lethal outlook gets challenged when Rachel saves Deckard’s life—and again when Batty rescues him from what certainly would have been a fatal fall. Now indebted to two replicants, Deckard decides to help Rachel evade the authorities (although his motives remain cloaked in mystery, so he could be up to something else entirely), having seemingly let go of his “don’t rock the boat” mentality and realized that it’s better to live outside the law than to commit atrocities to uphold it.

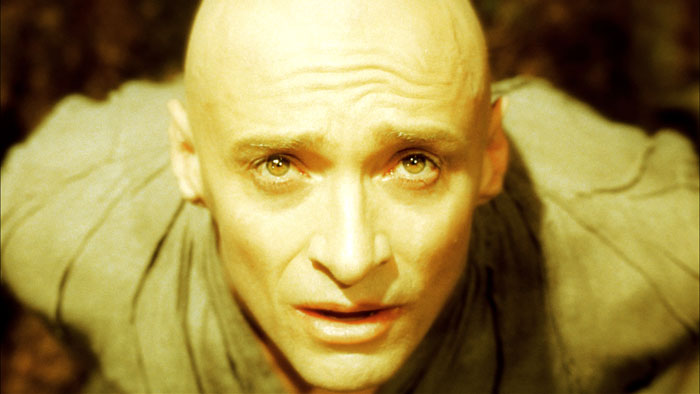

This revelation is echoed in Tommy’s tortured journey through “The Fountain,” which gets off to a grim start. Initially, Tommy is so obsessed with destroying the tumor that’s sapping away Izzi’s life that he neglects her while he frantically searches for a cure (it’s his way of handling his grief and demonstrating his strength in a situation where he feels emasculated).

In fact, Tommy refuses to give up even after Izzi dies—losing her convinces him to direct his rage against death itself. “Death is a disease,” he seethes. “It’s like any other. And there’s a cure. A cure. And I will find it.”

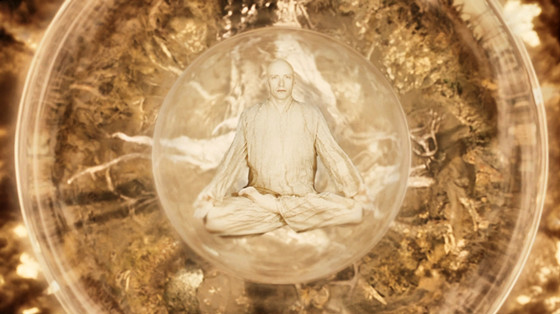

That conviction leads Tommy into the far reaches of space with the Tree of Life. Over the years, Tommy has used the tree to prolong his own life, and he knows that if he is able to heal it in the rejuvenating light of Xibalba, he will be able to live forever.

But the tree perishes before he can complete the mission, forcing him to recognize the pointlessness of his search for immortality and how tragically wrong he was to allow it to separate him from Izzi. And so, finally free of his obsession, he sacrifices himself to reanimate the tree, thereby letting go of his search for eternal life—just as Deckard was forced to abandon his hunt for replicants.

That said, it’s worth noting that of these two journeys, it’s Tommy’s that has the stronger emotional resonance. As meticulous as Scott is, he never peers too deeply into Deckard’s pysche, whereas Aronofsky makes us feel the full force of Tommy’s love, rage, grief, and peaceful acceptance of death. It’s an experience that is as cathartic as it is painful, an experience that makes it matter when Tommy finds to the strength to tearfully say the words that finally set him free: “Goodbye, Izz.”

5. Both films are box office bombs that gained respect over time

If there’s one thing that no one could accuse either “Blade Runner” or “The Fountain” of, it’s being a commercial smash. Scott’s film may have boasted special-effects vistas that matched “Star Wars” in beauty and technical virtuosity, but the film grossed under $28 million domestically and was considered a flop.

Then, when Aronofsky’s mystical magnum opus drifted into the midst of the 2006 awards season, the reaction was even more punishing: The film cost $35 million to make, but only sold under $11 in tickets domestically.

When ambitious, auteur-driven projects fizzle, it’s sometimes a cue for critics to come to the rescue. But too many reviewers refused to throw either Scott or Aronofsky a lifeline. Both of their movies bore the brunt of brutal verdicts from critics like Pauline Kael, who jeered in The New Yorker that “Blade Runner” “gives you the feeling of not getting anywhere,” and Anthony Lane, who, in the same publication, sneeringly wrote that the outer space scenes in “The Fountain” made Hugh Jackman look like “he might as well be trapped inside the world’s most beautiful beer commercial.”

For many films, such withering reactions would be a game-ending play. Yet “Blade Runner” refused to shrivel. In fact, when a 70-millimeter print of Scott’s original cut was screened at a Los Angeles film festival in 1990, the line to get into the theater went around the block, beginning a journey that led to the movie joining the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry and earning praise from a fan named Barack Obama.

Meanwhile, “The Fountain” has achieved a similarly long-gestating success. Despite its dismissive early reviews, it won a spot on a list of the 500 greatest films of all time (which can be viewed at http://www.empireonline.com/movies/features/500-greatest-movies/), while a collider.com list ranked it as one of the 25 best sci-fi films of the 2000s (although whether a movie that co-stars a magic tree can be classified as sci-fi is up for debate).

So why did it take “Blade Runner” and “The Fountain” so long to receive recognition? It could be that the flimsy characterizations of both films initially obscured the pleasures they offered (even though Ford and Jackman fearlessly scaled the emotional heights, they failed to imbue Deckard and Tommy/Tomas with any discernible idiosyncrasies); it could be that it simply took audiences a while to know what to make of both works; and it could be that Scott and Aronofsky cultists have, over time, simply grown loud enough to drown out many of the nonbelievers.

But at the end of the day, it doesn’t matter why “Blade Runner” and “The Fountain” finally found the accolades that initially eluded them. That success is overshadowed by Scott and Aronofsky’s real achievement: getting the two movies made in the first place.

6. Both films feature an ambiguous ending that raises as many questions as it answers

If a “Blade Runner” fan weaned on the director’s cut were to watch the 1982 theatrical version of the film, they’d be in for a shock: It ends not on the abrupt, ambiguous note that Scott prefers, but with Deckard and Rachel sharing a moment of romantic bliss. It’s a satisfying conclusion, but it was always too tidy to offer what Scott wanted to deliver (and what Aronofsky gave us decades later with the ending of “The Fountain”): something to talk about, wonder about, and lose sleep over.

The “Blade Runner” coda that fans know from the director’s cut begins with Deckard returning to his apartment after Batty saves his life. There, he and Rachel agree to go on the lam, but he stops to pick up an odd object as they depart: an origami unicorn, apparently left by Gaff. Deckard then remembers something Gaff said about Rachel—“It’s too bad she won’t live! Then again, who does?”—and then he and his newfound fellow fugitive exit. The last thing we see before the credits roll is a door closing behind them.

On the surface, the implication of this scene is clear: Since Deckard once dreamed about a unicorn, the origami could be Gaff’s way of letting him know that the vision was implanted in his mind and that he’s a replicant. But why would Gaff aid Deckard? What does Gaff’s mention of Rachel mean? Where is Deckard going? And if he is a replicant, will he only live for four years, as we’re told all current replicants do? Scott literally slams the door in our faces to keep us from answering those questions.

Aronofsky isn’t much more forthcoming in “The Fountain.” In the film’s last scene, he shows Tommy kneeling before Izzi’s grave, apparently accepting her death—a scene that appears to be set before Tommy journeys into space, consumed by his obsession with immortality. So what happened? Is planting the blossom simply what Tommy wishes he’d done, a fantasy that we’re privy to? Or is Aronofsky’s decision to end the film there a hint that the heightened conquistador and spaceship scenes were wild imaginings that Tommy submerged himself inside to combat his anguish?

It’s great fun trying to unravel these questions, even if they’re kind of beside the point. Because if you really want to understand “Blade Runner” and “The Fountain,” all you need to do is look at their defining moments. Moments like Deckard shakily telling Rachel he can’t kill her. Moments like Tommy joyously declaring, “I’m gonna die,” jubilant at the prospect of rejoining—in spirit—the woman he loves. Moments like a dying Batty sharing an unexpected moment of intimacy with Deckard and confessing that his extraordinary experiences “will be lost, in time, like tears in rain.” Moments like Tommy telling Izzi he’s too busy to go for a walk with her, but then running after her into the snow, just in time to catch up before she leaves him behind.

If there’s anything all those moments prove, it’s that beneath their labyrinthine twists, “Blade Runner” and “The Fountain” are about love. That, in the end, is what stays with you after you watch them—and what endures like tears in rain that refuse to be lost, no matter how hard the storm bears down.

Author bio: Bennett Campbell Ferguson is a freelance film critic and culture writer based in Portland, Oregon. In addition to reviewing films for Willamette Week, he founded the blog T.H.O. Movie Reviews, which he also edits.